People

After a Cancer Diagnosis, Tracey Emin Is Slowing Down—But Says Her Best Work Is Still to Come

The artist is opening a major show of new work at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels on October 30.

The artist is opening a major show of new work at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels on October 30.

Kate Brown

Early on in lockdown, Tracey Emin was working on a painting—a large and strange semi-abstract one—that was keeping her up at night. She spent days staring at it. A few months later, she figured out what it was she had been making: a picture of a malignant lump, just like the one growing in her body, unbeknownst to her at the time.

“It’s exactly the same as my bladder with the tumor in it, before I knew I had the cancer—it’s brilliant!” she tells me over the phone from her London home. In a year marred by crisis, Emin has been experiencing a very personal one: cancer.

After a diagnosis in the spring and an operation in the summer, she is now in remission—and determined to funnel her grit and gratitude into new work, as soon as she feels well enough to paint again.

While in treatment, she has been preparing to open a deeply cathartic show at two of Xavier Hufkens’s locations in Brussels. They feature drawings made during lockdown and a teeming array of 25 paintings from this year and the last. The topic, though, is one for the ages: love, in all of its nuances. “Details of Love” opens on Friday, October 30.

“The whole show is about the things that you notice when you’re in love,” she says, stressing that I shouldn’t confuse those elements with being in love. “The rain is beautiful when you’re in love… It’s about understanding those small dots, the small things.”

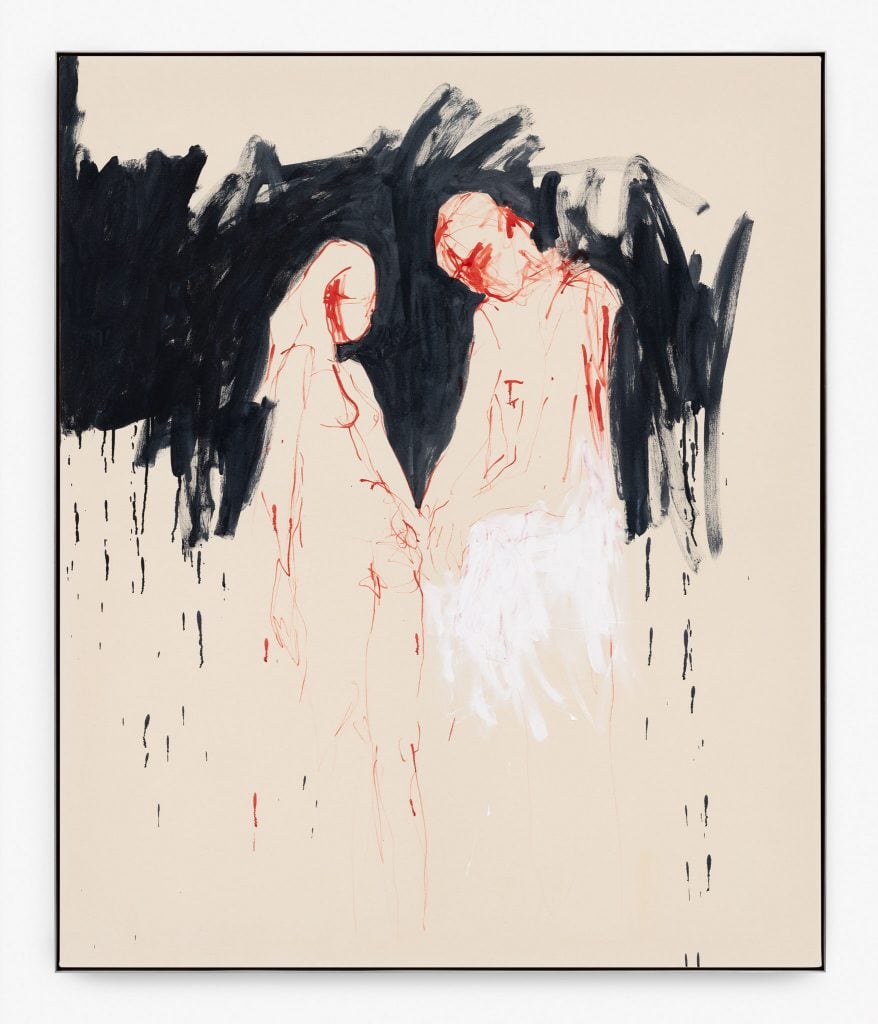

Tracey Emin, There Was A Moment (2019). Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

Emin’s relationship with love has been a through line for much of her work in recent years. She made international headlines in 2016 when she announced that she had married a stone in her garden of her home in the south of France. (The idea was widely ridiculed in the press, but it had genuine feeling behind it: to embrace her life as a single woman, her love of her materials, and her work.)

There has been a noticeable softening to Emin’s palette during this time, too—a move toward pastels and wispier silhouettes. The artist known for her condom-strewn My Bed and Everyone I Have Ever Slept With is still embracing raw feeling and the female body, but in a way that is less confrontational and more open to interpretation. The paintings in the Hufkens show ride the same wave as her critically acclaimed exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey, in early 2019.

Well before her diagnosis, Emin was making big changes: she decided to leave behind her longtime home of London and move by the sea, to Margate. She sold her Miami home. She stopped drinking and socializing for a while. She prioritized her inner world, a “pure” place for thinking and creating work.

Tracey Emin, I said I would say goodbye (2019). Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

“I had decided to change my life radically, in a split second,” she says. Now, she is almost finished packing up her London home. She has mourned the loss of her beloved pet cat. She is paring down. All of this change, she says, gave her strength to fight cancer.

Two months ago, she had many of her female reproductive organs removed. She now also has a stoma bag. It was not easy for the artist, who is known for bravely delving into the universe of female desire as well as frankly recounting her own sexual journeys and traumas. “They were going to remove my clitoris, but I stopped them!” she says. “I said, ‘keep it if you can’—and they have.”

What is most frustrating, she says, is that she has not yet been able to do the thing she loves most: paint. But she has been making photographs of her own body as an “existential” project.

“It feels like I only really got going in the last five years, that I started to understand what I am doing and what I am painting for,” she tells me. She says she has a lot of work “left to do” in her life, and—as an insomniac who loves what she does—it is hard to always be patient with her body. “Yesterday, I was crying because I wanted to paint and I didn’t have the energy to do it.”

She stops short of complaining, however—she doesn’t see the point. Besides, she’s tired of having been dubbed someone who moans. The deeply autobiographical and confessional nature of Emin’s character and work has not always fared well with critics. When she spoke with unusual frankness about trauma, rape, and abortion, some dismissed her as vulgar and self-absorbed.

“Now, there is a language for women to express themselves, thanks to #MeToo,” she says. “It’s good that times are catching up, but I wish I hadn’t been accused of being narcissistic back then.”

Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photo: Allard Bovenberg, Amsterdam.

Given her health and the ongoing cross-border travel complications, she won’t be going to Brussels for her opening. (“It’s going to be a fucking mess,” she says of the COVID-19 outbreaks across the UK and US.) But she’s never particularly liked openings, and she enjoys the intimacy of online viewing (“I can just sit in bed”). Her one wish? To have an intimate opening dinner with Xavier Hufkens, her longtime dealer.

“Tracey has always remained loyal to her purpose: making art, and she does so with steadfast commitment, raw energy and abiding passion,” Hufkens says. “Her paintings are psychologically forceful and crash into you like a tidal wave, yet they are also full of subtleties and vulnerable details.”

This description certainly applies to the works on view, though Emin prefers a more brash tagline: they are “really fucking wild,” she says. Not quite self-portraits, she labels them “self-feelings” or “inner projections.” There are bodies huddled together, kissing, sleeping, tangled in sexual encounters. The paintings and drawings seem to have breath and emotion coursing through them.

Tracey Emin, I found my way to the lake (2019). Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

As with much of Emin’s art, the paintings and drawings are a manifestation of memory work, which Emin says is conjured mystically, as one’s future is by a fortune teller. Looking at the complete body of work now, she supposes it could also represent a “wanted emotion” or something from the past, given that she has not been in love for a decade.

“I had fucking cancer, and having half my body chopped out, including half my vagina,” she says, “I can feel more than ever that love is allowed.” Being older, and on her own, doesn’t mean she feels any less; quite the opposite is true. She is brimming with desire to experience life and make new paintings as soon as she can.

“At my age now, love is a completely different dimension and level of understanding,” she says. “I don’t want children, I don’t want all the things that you might subconsciously crave when you’re young—I just want love. And as much love as I can possibly have. I want to be smothered in it, I want to be devoured by it. And I think that is okay.”

Tracey Emins’s “Detail of Love” opens on October 30 and runs until December 19 at both Xavier Hufkens locations in Brussels.