Archaeology & History

Two Segments of an Ancient Mummy Wrapping Have Been Digitally Reunited to Reveal a Hieroglyphic Guide to the Afterlife

It remains unclear why the pieces were dispersed to different parts of the world.

It remains unclear why the pieces were dispersed to different parts of the world.

Artnet News

Two pieces of a mummy wrapping, once contiguous and later dispersed to opposite sides of the world, have been reconnected digitally. Together, they reveal scenes and spells from an ancient Egyptian text meant to guide the dead.

After the University of Canterbury in New Zealand catalogued a newly digitized image of one of the fragments, which has been in the collection of the school’s Teece Museum of Antiquities for nearly five decades, researchers at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles pieced it next to a shroud from their own holdings. The fragments, it turns out, fit together like a long-lost puzzle.

The news was announced last month by the University of Canterbury. “There is a small gap between the two fragments; however, the scene makes sense, the incantation makes sense, and the text makes it spot on,” said Alison Griffith, an associate professor in the school’s Classics department, in a statement. “It is just amazing to piece fragments together remotely.”

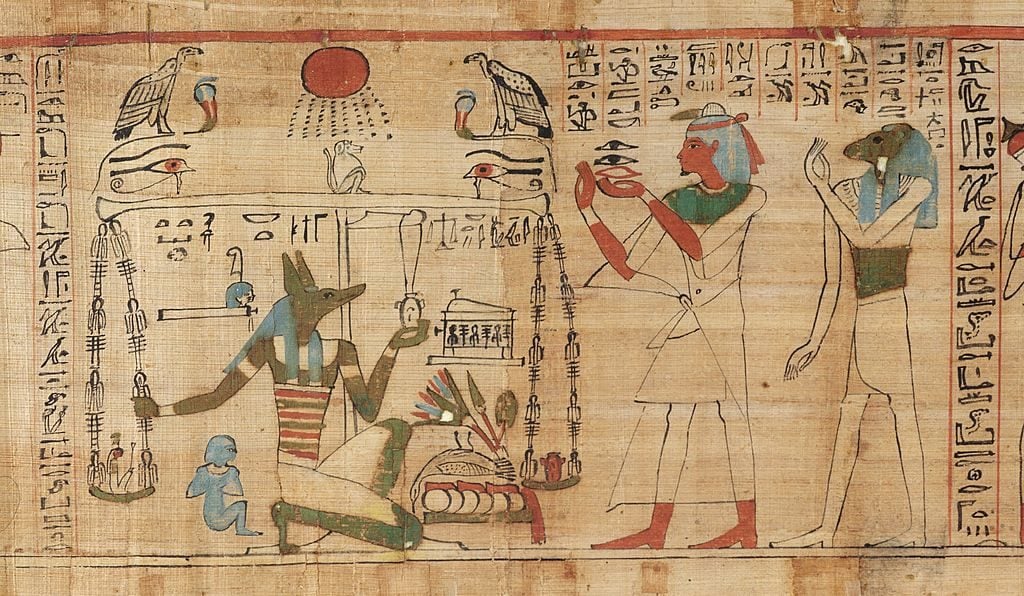

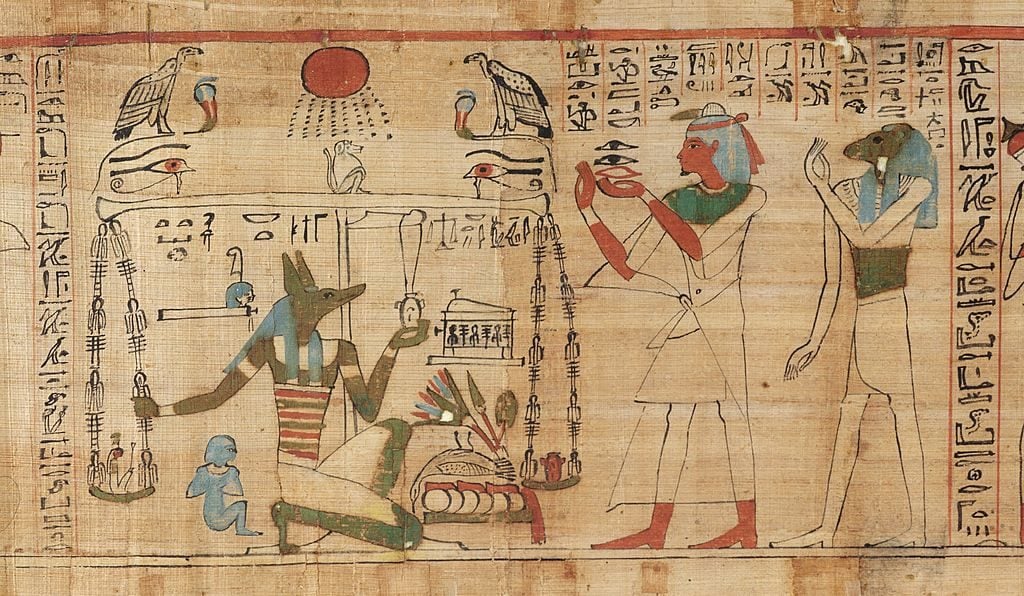

Both pieces of linen are covered with hieroglyphics from the Book of the Dead, an Egyptian funerary manuscript meant to assist a deceased person as they make their way through the underworld to the afterlife. On these particular segments are pictures of butchers cutting up an ox; a funerary boat with the goddesses Isis and Nepthys; and a figure dragging a sledge decorated with a picture of Anubis, the Egyptian God of the Dead.

A similar configuration of scenes is located in the Book of the Dead on the Turin Papyrus.

![[R] The University of Canterbury's fragment held at the Teece Museum of Antiquities and [L] the adjoining fragment from the Getty Research Institute. Courtesy of the University of Canterbury.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2021/07/Mummy-wrap-fragments_Courtesy-of-the-University-of-Canterbury-1024x211.png)

[R] The University of Canterbury’s fragment held at the Teece Museum of Antiquities and [L] the adjoining fragment from the Getty Research Institute. Courtesy of the University of Canterbury.

The segments came from a set of bandages that once enveloped a man named Petosiris, according to Foy Scalf of the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute. “Fragments of these pieces are now spread around the world, in both institutional and private collections,” Scalf said. “It is an unfortunate fate for Petosiris, who took such care and expense for his burial.”

How and why the two pieces of cloth were separated remains unknown. But there may be another clue on the way: another possible match has already been identified in a fragment from the University of Queensland, Australia.

The University of Canterbury’s segment entered its collection in 1972 when a professor purchased it on behalf of the school at a Sotheby’s sale in London. Prior to that, it lived in the hands of Thomas Phillips, a well-known antiquary collector, who acquired it from Charles Augustus Murray, the British consul general in Egypt from 1846-63.

The Getty Research Institute did not immediately respond to an inquiry about the history of its own fragment.