Art World

As the UK Bans the Sale of Elephant Ivory, What Will it Mean for Museums and the Antiques Trade?

Many dealers lobbied hard against the strict new ivory law that will mean up to five years in jail for convicted offenders.

Many dealers lobbied hard against the strict new ivory law that will mean up to five years in jail for convicted offenders.

Naomi Rea

The UK government has passed a groundbreaking bill that will impose a near-total ban on the trading of objects made of elephant ivory in the country. The ban covers artifacts no matter how old they are, with a few very narrow exceptions that some in the antiques trade fought hard to expand.

Amid the stalemate in the UK Parliament over how to leave the European Union, the historic bill gained cross-party support, passing its final hurdle on Tuesday. The Queen gave it her royal assent today, December 20, so the bill should come into law within around six months. Her grandson, Prince William has made saving elephants and wildlife crime a personal cause. Anyone caught breaking the new law could be jailed for up to five years.

The UK environment secretary Michael Gove has said the ban is one of the world’s toughest, granting fewer exemptions than those allowed by the US ban when it was introduced in 2016 or China’s, which came into effect at the beginning of this year.

Under the new regulations, there is likely to be a great number of artworks and antique objects that will no longer qualify to be legally traded. Many antiques dealers fear their businesses will crumble. They have long argued that crippling the antiques trade will do little to stop poaching today.

London-based Max Rutherston, who specializes in Japanese netsuke, told artnet News that the new law will be “disastrous.” Calling it ill-judged, he said that: “As all who have fought the bill know, and have stated vociferously, there is no connection between the trade in antique ivory and the poaching of these magnificent beasts.”

He says the cultural effect of the bill will be far-reaching and disastrous. “Works of art that have been treasured for centuries, and which are of significant historical significance, will be outlawed overnight. Meanwhile the selling of ivory will continue unaffected in the rest of Europe, so ‘bravo,’ lawmakers, for putting sections of Britain’s world leading antique market out of business.” Come the end of March, Rutherston says his business, which has thrived for eight years, will become unworkable in the UK. “In order to continue I shall almost certainly have to exile myself,” he said.

The law restricts trade, not display, so museum collections that are already in existence will be largely unchanged, although not immune from criticism. In June, the British Museum was forced to defend accepting a gift of more than 500 historic Chinese ivory figures collected in the early 20th century by the China-based hotelier Victor Sasson, saying the acquisition did not endorse the contemporary trade elephant ivory.

A spokeswoman for the British Museum told artnet News that it “fully supports” the government ban on the sale of ivory from all living species of elephant. “The British Museum supports any efforts to protect elephants in Africa and Asia and to curb the illegal trade and export of ivory,” the spokeswoman said.

Elephants carved from illegal Ivory are displayed at an “Endangered Species” exhibition at London Zoo in 2011. Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images.

“As a national museum with collections featuring many significant historic objects made from ivory, we welcome the fact that the Ivory Bill includes a few important but limited exemptions for historic ivory relevant to museums like ours. These objects are integral parts of the collection, and play an indispensable part in the Museum’s presentation of the history of human cultural achievement.”

The new law includes a number of exemptions. Notably, items that are examples of “the rarest and most important items of their type” and were made more than 100 years ago will still be permitted to be traded. For the first time museums will play an important role in defining what objects meet these criteria.

Outside of this, there will be an exemption for objects made before 1947 that are less than 10 percent ivory. This is the so-called “de minimus” exemption that many dealers fought hard to expand. Musical instruments containing less than 20 percent ivory, which were made before 1975—the date that Asian elephants were listed as an endangered species—will also be exempted. Lastly, portrait miniatures more than 100 years old that are painted on thin pieces of ivory, also qualify for exemption. In order to be traded, qualifying items will need to be registered online at a fee.

Antiques dealers lobbied hard to avoid a total ban, and are now unhappy with the “de minimis” exemption, which they say is so low that pretty much every object with a solid ivory handle will not qualify. Many precious ivories including Japanese okimonos and netsukes, French Dieppe carvings, and African artifacts, might not pass museum-quality muster either, and so will no longer be able to be sold in the UK.

Antique dealer Martin Levy, who is the director director of H. Blairman & Sons Ltd, told artnet News that the bill was inevitable ever since it first came before parliament, because it had cross-party support. While Levy applauds the aim of the bill to protect endangered species, he calls it an example of “gesture politics.”

“In terms of how works of art have become tangled up in this, it’s a poor, ill-thought out piece of legislation that risks causing immeasurable damage to our universal cultural inheritance,” Levy said.

“On the face of it, it looks as though hundreds and thousands of perfectly genuine works of art created over millennia will be excluded, and banned from movement, because they are 100 percent ivory. They’re remarkable, but may not reach the bar of ‘outstanding,’ or however the government intends to define that. That will mean that they will cease to be collected, cease to be studied, and they’ll no longer circulate to inform generations about their past.”

He said that the next step for dealers will be to encourage the government “to think pragmatically” about how to implement the rules. “I think what they need to do is to be very mindful of not simply wiping everything out because bureaucratically it is going be easier for them.”

An ivory netsuke. Photo by Erich Ferdinand via Flickr.

Environmentalists hold that the true victors in all this are the elephants. The International Fund for Animal Welfare calculates that at least 20,000 elephants are killed each year for their tusks. Wildlife conservationists have welcomed the bill, which they hope will help to curb that figure.

Mark Jones, the head of policy at the UK wildlife charity Born Free told artnet News: “The passing of the UK Ivory Bill into law will vindicate [our] long-standing assertion that only by banning the trade in ivory can we hope to bring an end to the poaching of elephants, who are being slaughtered on an industrial scale to provide the market with tokens and trinkets.”

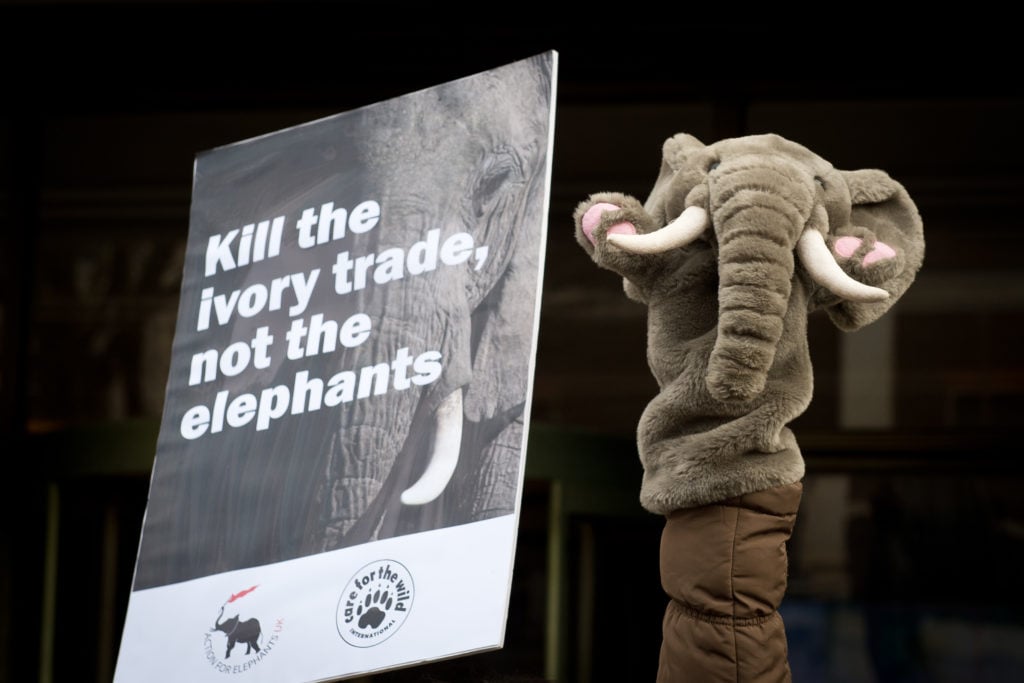

Ivory trade protesters in London in 2014. Photo by Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images.

Some conservationists are arguing that the law does not go far enough. They fear it will have unintended consequences on other endangered species, as pressure increases on traders to maintain the supply. It is expected that the law will be extended to cover these alternative sources of ivory after the government holds another consultation on the matter in July.

“The government must ensure the licensing and enforcement authorities have all the tools and resources they need to effectively implement the restrictions; ensure that there are no loopholes; and make good on its promise to immediately consult on the inclusion of ivory derived from other species, including hippos, narwhals, walruses and warthogs, in the ban,” Jones said.

But it does not stop there. The next step for conservationists is to lobby the UK government to sway other jurisdictions to introducing similar restrictions. “The EU would be a good place to start,” Jones said.