Museums & Institutions

Winterizing Monuments, Digitizing Archives: How Ukraine Is Fighting to Preserve Its Cultural Heritage a Year Into the Russian Invasion

UNESCO has identified damage to 241 cultural heritage sites in Ukraine since February 2022.

UNESCO has identified damage to 241 cultural heritage sites in Ukraine since February 2022.

Eileen Kinsella

As the world marks a year since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (February 24), there are vigorous ongoing efforts to both assess damage to cultural heritage in the country, and find ways to protect and preserve it. Despite the challenges of doing so amid the broader devastating effects of the war, it nonetheless remains a key focal point of both activists inside the country fighting to preserve art and monuments, as well as outside watchdog organizations and authorities that continue to offer major support.

In the early days of the war, Kyiv-based museum veteran Milena Chorna banded together with several colleagues to form the Ukraine Museum Crisis Center. Currently, Chorna works at the War Museum, known formally as the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War, Memorial Complex.

Installation view of “Ukraine-Crucifixion” at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War. Memorial Complex, Kyiv.

Curator: Dr. Jurii Savchuk, designer: Anton Logov, photo: Andrzej Markiewicz

“Collecting, preserving, and revealing to the world, the stories and artifacts of the Russo-Ukrainian war is the priority mission for the museum in this darkest hour for our nation,” said Chorna. “Since the first day of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the museum took an active position at the cultural and informational fronts in order to shed light on the crimes of the aggressor and appeal to the world to resist the total evil together with us.”

As of last week, UNESCO had identified damage to 241 sites since February 2022. This includes 106 religious sites, 18 museums, 86 buildings of historical and/or artistic interest, 19 monuments, and 12 libraries. That is an uptick of 80, compared with 161 sites cited by UNESCO as of July 2022, roughly five months into the war.

Not surprisingly, the toll as documented by observers inside the Ukraine is far higher. The latest number according to website Culture Crimes, states that there are 553 damaged and destroyed objects of cultural heritage and cultural institutions of Ukraine. That is more in line with a late August report in the Kyiv Post stating that 492 Ukrainian cultural heritage sites and cultural institutions have been impacted by Russian attacks, “and the number is rising.”

As Artnet News reported previously, by spring 2022, there had already been widespread looting by the Russian military of valuable artworks and historic gold collections in cities including Mariupol and Melitopol. In a number of cases, it was unclear whether missing objects and collections had been successfully hidden away for safekeeping or had been destroyed or stolen.

Statues protected by sand bags in front of St Michael’s golden-domed monastery, Kyiv Ukriaine, July 7, 2022. Photo: Niall Carson/PA Images via Getty Images.

Making matters even more complicated, sources said it was often not clear what was the exact affiliation some of the groups seizing works had or have. In one case, Chorna said, “they were not soldiers but appear to have some military background,” but no clear identifying marks or insignias. “They come prepared with lists,” she said, adding that it was unclear whether the lists “are provided by someone local or did they get this just by browsing the Internet.”

Bénédicte de Montlaur, president and CEO of the World Monuments Fund, told Artnet News in a phone interview: “Heritage has been very impacted by this conflict, and it’s a conflict very much about history and identity.”

While it’s not unusual that heritage is generally impacted in times of conflict, she said, “in Ukraine, the situation is specific. It’s about Ukrainian history and identity, so we’ve seen many heritage places impacted as collateral damage or sometimes… directly targeted,” as President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has alleged in the past, even if the allegations of targeted destruction are more difficult to prove.

Bénédicte de Montlaur, President and CEO, World Monuments Fund. Image credit: Kat Harris Photography 2022.

Last week the WMF and the J. Paul Getty Trust’s annual Paul Mellon Lecture focused broadly on the intentional destruction of culture during conflict. Former Getty director James Cuno was the keynote speaker at the New York event at the Museum of the City of New York, where he discussed the matter in the context of a newly released book Cultural Heritage and Mass Atrocities, followed by a panel with de Montlaur and other UNESCO leaders.

Meanwhile, WMF mobilized from the start of the Ukraine war and immediately engaged in advocacy work, raising awareness about the importance of protecting cultural heritage during times of conflict. A generous $500,000 grant from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation (formed in memory of the eponymous Color Field painter) allowed it to immediately recruit staff.

In November, the Getty gave a $1 million grant to Ukraine to help fund safe art storage within the war-torn country, conservation and protection of monuments, and salaries for Ukrainian heritage professionals.

Notably, the WMF hired local professional Kateryna Goncharova, a former Fulbright scholar with a Ph.D. in museum and monuments studies. Goncharova spoke to Artnet News via phone from Cherkasy, in Central Ukraine, where she relocated from Kyiv, about on-the-ground efforts including “winterizing” exposed monuments and digitization of archives. She said she is proud of the stabilization and preservation efforts so far “despite the situation we’re living in.”

WMF has been coordinating with international partners such as UNESCO and Blue Shield. Having “local partners with someone on the ground makes a big difference with coordinating emergency actions,” said de Montlaur. They have partnered with Cultural Emergency Response (CER), with local support from the Heritage Rescue Emergency Initiative (HERI).

Kateryna Goncharova, Ukraine Heritage Crisis Specialist, World Monuments Fund.

For instance, WMF sent more than 400 fire extinguishers specifically destined for historic wooden churches. “That’s important because [the churches] are very vulnerable. Very often when you extinguish fires, this is when you actually destroy heritage,” said de Montlaur.

Other targeted efforts include “winterization” in the form of temporary coverage of monuments, such as the Sophia Cathedral which had been damaged as well as those that were already undergoing renovation and thus exposed, when the war started. WMF has also been coordinating efforts to digitize the state archive of Kyiv Oblast, an administrative region in north-central Ukraine.

We asked de Montlaur about the challenges of coordinating preservation and recovery efforts when the war is ongoing and there is still so much uncertainty. We have now entered the “second phase which is damage assessment,” she said. “This is paving the way for the future when the situation will hopefully stabilize.”

De Montlaur continued: “We’re trying to do as much as we can given the situation right now so we are doing things while also preparing for the future.” Past conflicts in places like Syria and Turkey have provided critical lessons. “There is a pattern. The first thing is to raise awareness about heritage at risk. The second thing is to talk with your partners both international and local.”

Chorna also provided Artnet News with updates on what War Museum director Dr. Yurii Savchuk and his team have been doing.

“Once the artifacts of the collection and the international exhibition, curated by Savchuk, titled ‘Forever Free Ukraine,’ were secured, the team focused on collecting the artifacts, oral history, and other materials, in order to document the ongoing war,” said Chorna.

Whenever a region was liberated, she said, the War Museum went there first: Kyiv and Chernihiv regions were freed up April 1 and April 2 respectively, and the team began an expedition on April 3 that ran until April 16. The Kharkiv region was liberated September 10 and the team expedition was held from September 13 to 18. Kherson was liberated November 11 and the director was there on November 12, collecting the artifacts.

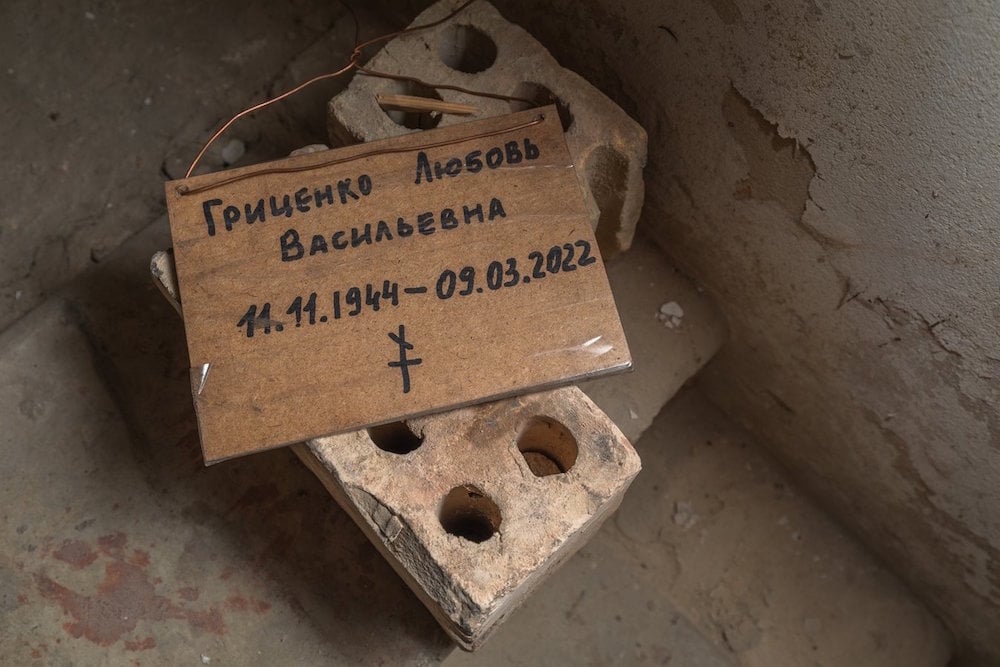

An artifact from Hostomel bombshelter at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War. Memorial Complex, Kyiv.

Image courtesy the War Museum.

Chorna said at present there have been over 30 expeditions held and over 7,000 artifacts collected, more than 5,000 of which have already been examined and studied. This work resulted in a number of exhibitions, the core one being “Ukraine – Crucifixion,” the first exhibition in museum practice about the ongoing war, which was created in real-time.

It opened in May 2022 and “is still of great interest to both domestic and foreign visitors. Thus, we find it crucial to continue with the museum work after the collections have been secured, to go on collecting the vanishing evidence of the ongoing war and save the damaged cultural heritage, research and document all of the aforementioned materials in order to present the world with the realistic picture of the Russo-Ukrainian war from the museum and historical perspective,” said Chorna.

In a recent interview posted to the WMF site, Goncharova stressed the important of cultural heritage preservation, saying: “Restoring a monument that was destroyed gives people a reason to withstand whatever the circumstances we have to face, whatever challenges may come. It gives us something to look forward to. So continue believing in Ukraine, continue believing in our future.”