Art World

Marina Abramović and Ulay Are Reuniting to Write a Joint Memoir

The famed duo will collaborate once again.

The famed duo will collaborate once again.

Sarah Cascone

The greatest duo in the history of performance art, Ulay and Marina Abramović, will reunite to write a book about their 12-year partnership.

“There are so many unbelievable anecdotes which most people don’t know, and I think they’re worth reading—they will sound like fairy tales,” Ulay told artnet News at the opening of his current exhibition at New York’s Boers-Li Gallery last week.

He had arrived in the city earlier in the day, having checked out of the hospital in Amsterdam just the day before. “I feel a little bit like a ghost,” but missing the show wasn’t an option, Ulay said. “I didn’t want to disappoint anyone.”

Abramović has agreed to the new collaboration, Ulay added, admitting that he was excited about the prospect of the pair teaming up again.

Marina Abramovic and Ulay at the MoMA. Photo by Scott Ruddl.

“Marina had an opening two weeks ago at the museum in Bonn. I was there, and I also gave a public talk. During the talk, it dawned on me. ‘Hey, there’s something we didn’t do: writing our memoirs,” the artist said of the project’s inspiration. “Therefore, we maybe meet in August to get together for 10 days or two weeks to work on this manuscript.”

Not too long ago, such a project would have seemed inconceivable. Following a dramatic split atop the Great Wall of China in 1988—a 90-day-long performance art piece titled The Great Wall Walk that was originally planned to end with a wedding—the pair did not speak for decades.

The relationship thawed in 2010 when Ulay made a surprise appearance at “The Artist Is Present,” Abramović’s blockbuster at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. She had adapted one of their durational performance works, Nightsea Crossing (1981–87), in which the two artists sat facing each other for hours on end, for the exhibition’s titular piece. Abramović spent the entirety of the show’s run at the museum, silently sitting opposite museum visitors. When Ulay stepped in, the two cried and held hands, a touching moment that quickly went viral.

As a solo artist, however, Abramović had suddenly become a superstar, more famous in her own right than for the work the two had done together, adding a new strain to her relationship with Ulay. In 2014, Abramović refused to allow Ulay to reproduce images of their joint works in his 2014 book Whispers: Ulay on Ulay, which instead featured pink squares in place of the contested photographs.

This triggered a lawsuit, with Ulay claiming he was owed royalty money from their shared works, based on the terms of a 1999 contract. He won the case in 2016.

Just a year later, however, the two were on very different terms, reuniting for Abramović’s retrospective at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art outside Copenhagen.

Ulay and Marina Abramović at the opening of “Ulay: Renais Sense” at Boers-Li Gallery in New York. Photo courtesy of Boers-Li Gallery, by Ember Hua.

“We came to this moment of real peace,” Abramović said in a documentary about their relationship filmed by the museum. “I think of this life that left this really beautiful work that we left behind, and this is what matters.”

Ulay, meanwhile, has revived his art career, returning to performance after years of relative silence following his breakup with Abramović. (“For her, it was very difficult to go on alone. For me, it was actually unthinkable to go on alone,” he told the Louisiana Channel.)

The exhibition at Boers-Li, titled “Renais Sense,” features a room of the pair’s collaborative work, including a video of their first performance, Relation in Space (1976), in which the two, completely naked, ran toward each other over and over, colliding with increasing force until Abramović collapsed from exhaustion.

The focus of the show, however, is Ulay’s photography, particularly his 1972 “Renais sense” series—work that he made prior to meeting his more famous partner. “Almost nobody knew what I did before my collaboration with Abramović,” Ulay said.

He’s also been busy. Since 2011, in particular, he’s been compiling the Earth Water Catalogue, a database of projects to improve the quality and availability of drinking water and raise awareness about the issue, from artists, technologists, architects, and designers. Ulay took the name from the historic San Francisco-based counterculture magazine Whole Earth Catalog, which offered readers tips for sustainability, independence, and self-sufficiency.

An Earth Water Catalogue website is scheduled to launch this year. “Water is an incredible, wonderful, subtle medium,” Ulay said. “There are many artists who have done projects with water already, and they can join and add photographs, videos, sound recordings, text, whatever.” He has also solicited submissions by mail, sending blank postcards out to artists. The artworks sent in return will be the basis for an upcoming mail art exhibition at De Appel in Amsterdam.

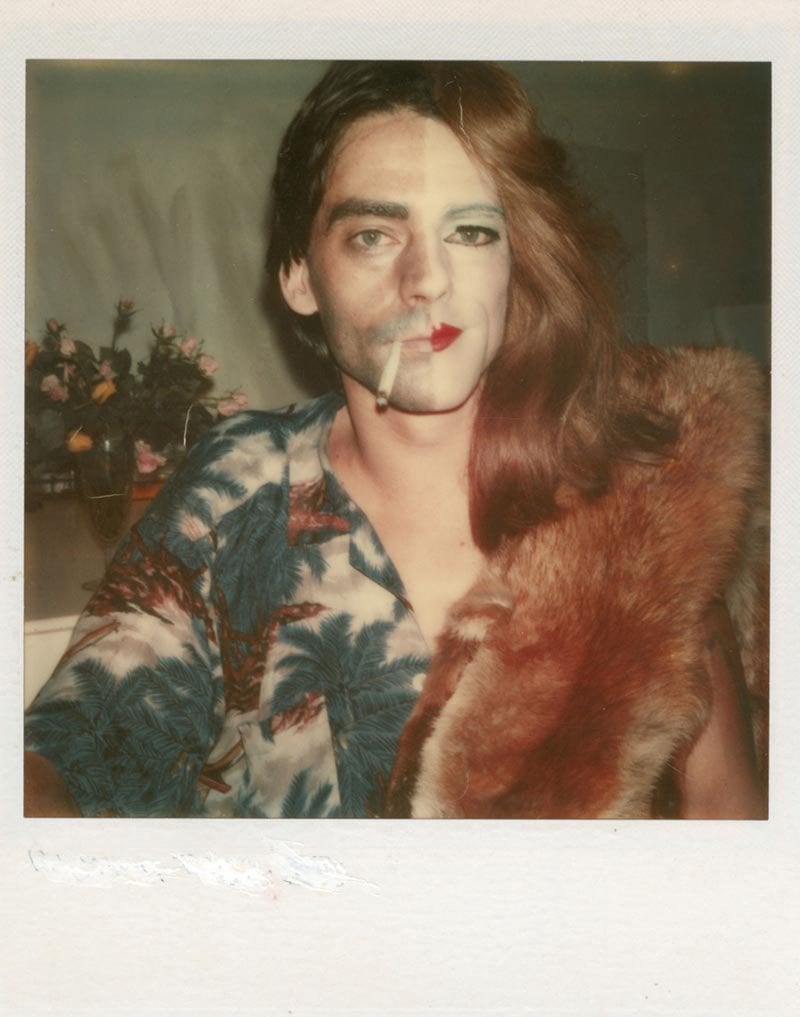

Ulay, S’he from the series “Renais Sense” (1973–4).

Last week’s opening marked Ulay’s first solo Manhattan outing since 1992’s “Long Playing Record: The Homeless Project” at Vrej Baghoomian Gallery. “It was a great show, but it was not reviewed at all,” Ulay recalled. “It was all about the civil rights movement, and people thought ‘here comes this arrogant European artist to remind us of civil rights art.’ It was maybe a little mistake.” (He also had a show at Brooklyn’s Kustera Projects, titled “Watermark/Cutting Through the Clouds of Myth”, in 2016.)

With “Renais Sense,” Ulay has done a better job of tapping into the current zeitgeist. “It’s from the early ’70s, but it’s not dated,” he said of the titular body of work, a group of self-portrait Polaroids that show Ulay exploring his feminine side, cross-dressing as a woman.

Engaging with the concept of gender fluidity long before it became a marketable trend, Ulay was inspired by the psychology of Carl Jung and the concept of the anima and the animus, the male and female parts of the soul found in every person.

“I like to remind the audience that I was busy very early with the subject,” he said. “It was more emotional than rational…I think my anima was knocking on my door of consciousness, so I answered the voice of my anima in order to satisfy this part of my female soul.”

When asked how the works read now, Ulay admitted that he was not aware of the work of younger artists addressing issues of gender identity, but that he was happy to learn about it. “I think it’s time to push it one more time,” he said. “I think we should be more radical… the famous slogan I had was ‘aesthetics without ethics are cosmetics,’ and it is more than ever the case today.”

“Ulay: Renais Sense” is on view at Boers Li Gallery, 24 East 81st Street, New York, May 4–June 23, 2018.