Ulysses Jenkins’s career arc takes one through the annals of Los Angeles art history, and back to the beginnings of video as a communications technology and a tool of artistic expression.

From his interrogation of the relationship between the oppressive moving image media and Blackness in pieces such as Mass of Images (1978) and Two Zone Transfer (1979), to his nearly daylong happenings (Dream City from 1983), Jenkins gestures to the potential of video to facilitate experimentation and collective self-determination.

Jenkins was born in 1945 and grew up near Central Avenue, the historic neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles known for hosting Black jazz pioneers at the Dunbar Hotel in the 1930s and 1940s. Later, he moved westward to the area around Culver City, where many movie studios were located.

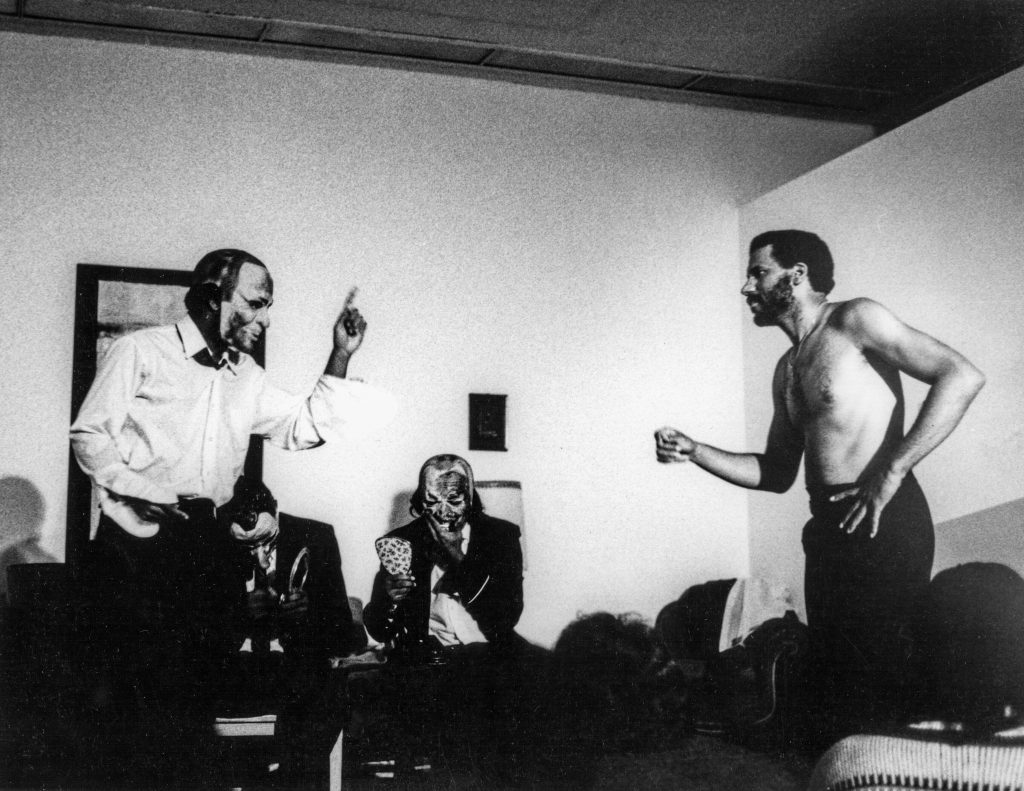

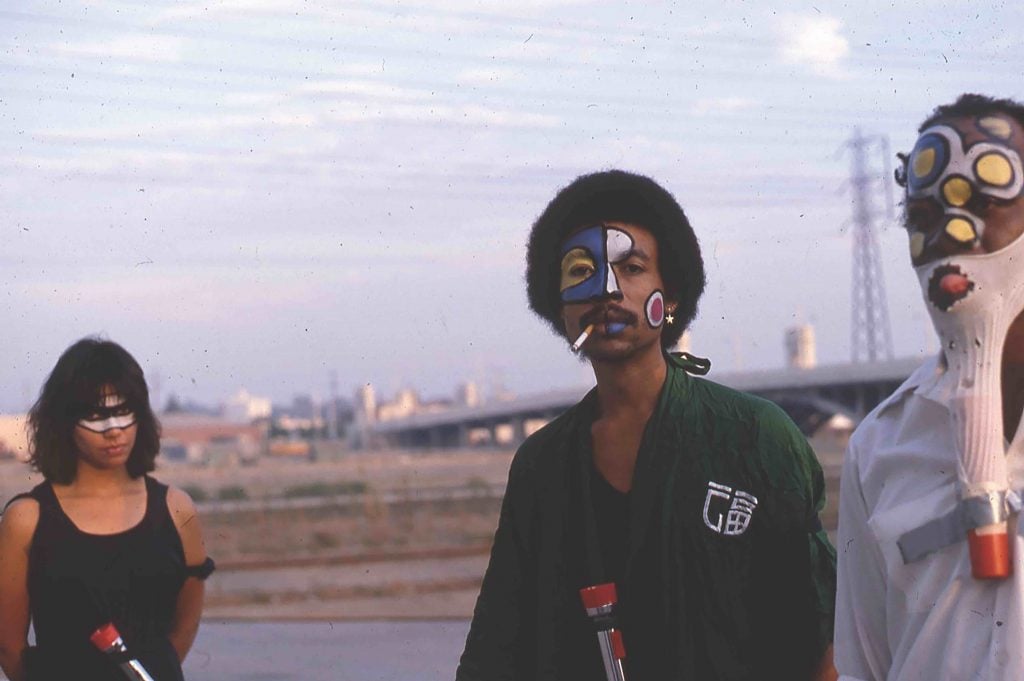

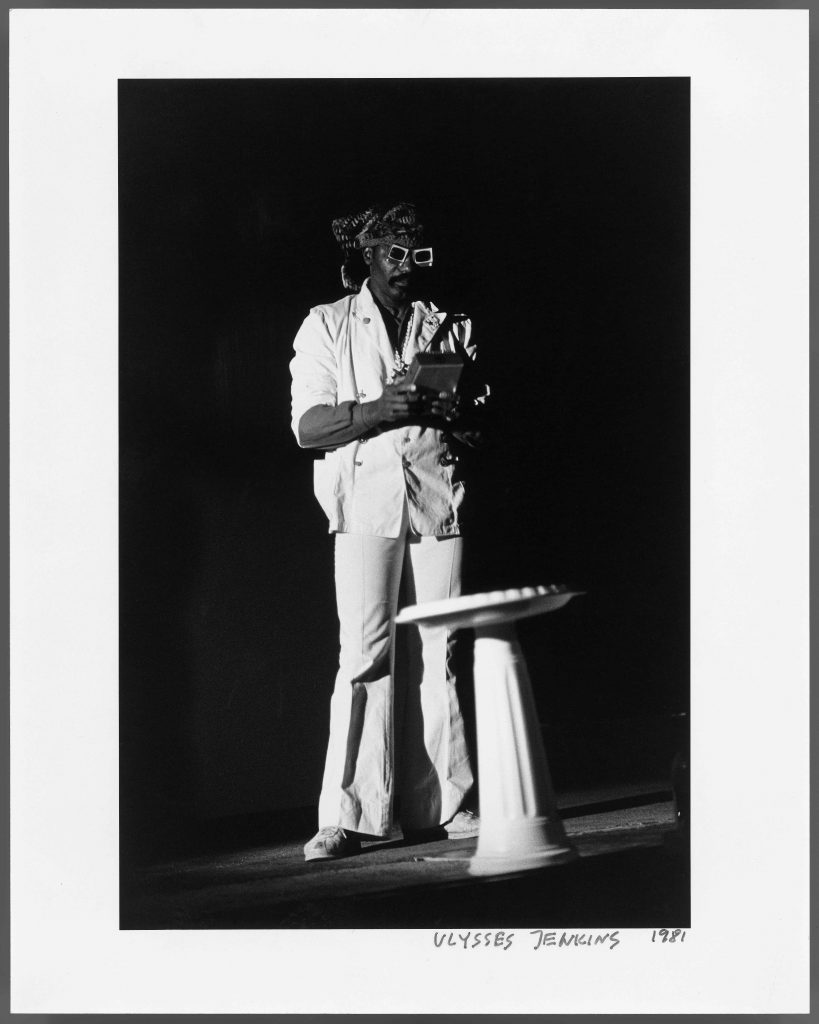

Ulysses Jenkins, Two-Zone Transfer, performance (1978). Courtesy of the artist and the Hammer Museum. Photo: Ilene Segalove.

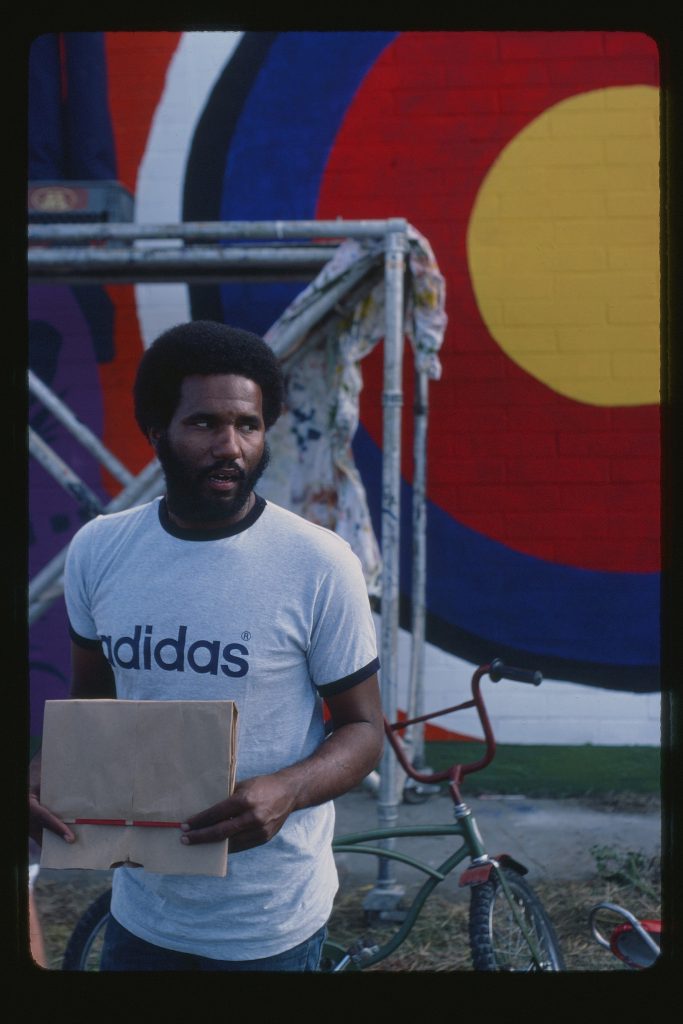

Before moving into video and performance, Jenkins was a painter and muralist. He worked as part of an intergenerational team with painter and educator Judith F. Baca on the historic Great Wall of Los Angeles. Jenkins studied under painter and printmaker Charles White, assemblage artist Betye Saar, and media theorist Gene Youngblood in the late 1970s. Kerry James Marshall was his classmate and collaborator.

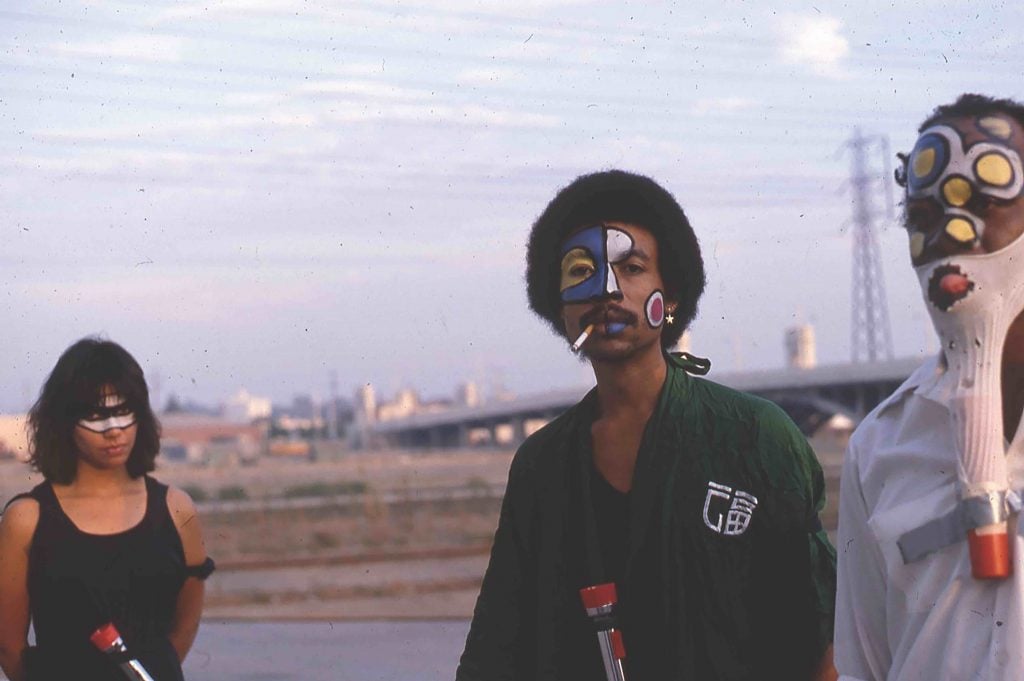

Jenkins contributed to an arts ecosystem based on collectivity by participating in the influential artist group Studio Z with artists David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Senga Nengudi, John Outterbridge, and filmmaker Barbara McCullough in the 1980s, and founding the artist studio and performance group Othervisions. Jenkins also collaborated with the East L.A.-based Chicanx collective Asco members Harry Gamboa Jr., Juan Garza, Daniel Joseph Martinez, and Patssi Valdez, and with filmmaker and community educator Ben Caldwell as part of Electronic Cafe, a tele-collaborative network connecting informal public multimedia communications venues founded by Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz.

Jenkins’s burgeoning interest in video began when he co-founded the media collective Video Venice News in 1972 and documented the Watts Summer Festival.

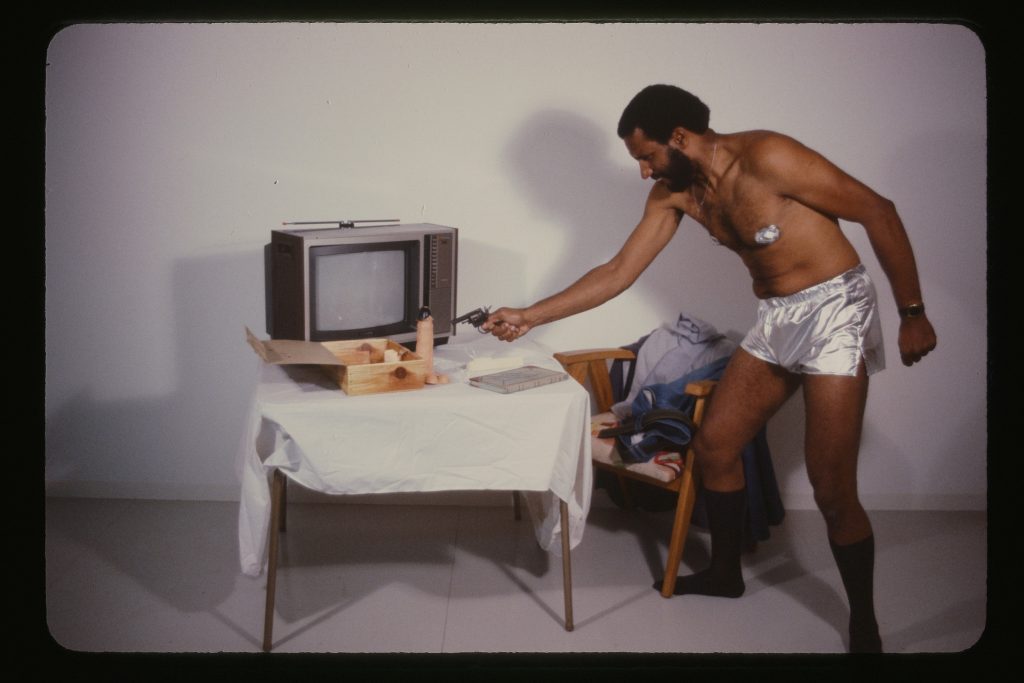

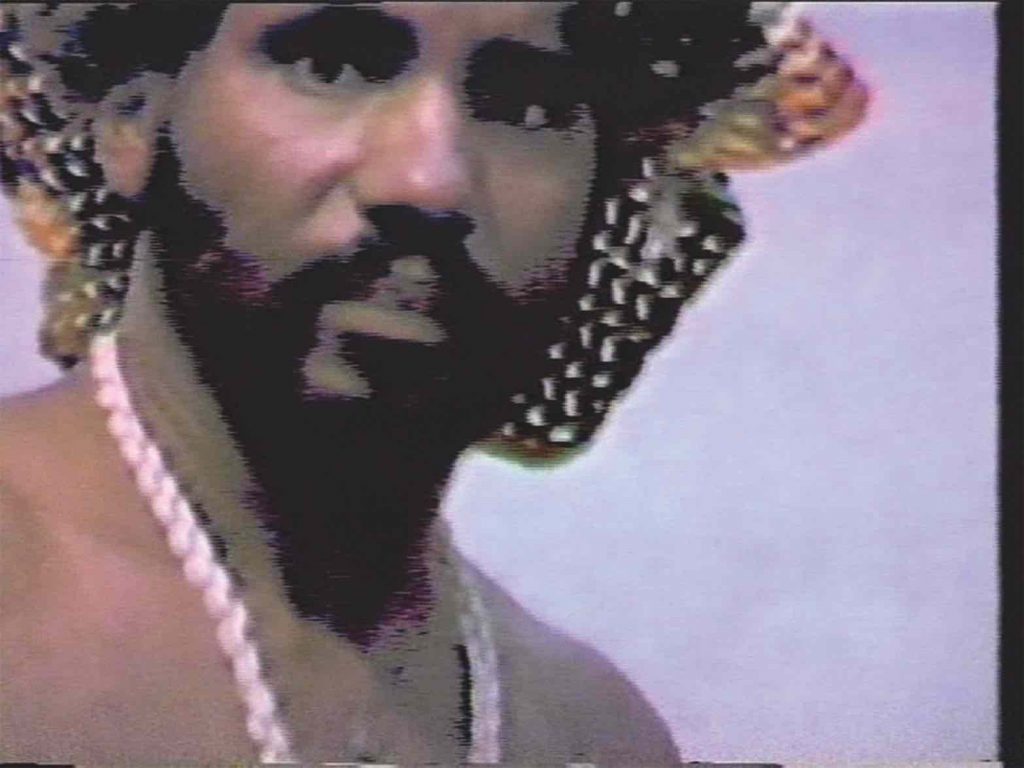

Ulysses Jenkins, Two-Zone Transfer, video still (1979). Courtesy of the artist, Electronic Arts Intermix, and the Hammer Museum.

Jenkins saw this as a way to employ video to counteract the negative images of Watts propagated by the mainstream media. Remnants of the Watts Festival (1972–73) is both a document of a community, and documentation of Black art. The video features on-the-street reporting and conversations with community members, as well as interviews with festival organizers like Claude Booker, curator of the art exhibition section, who gives a walkthrough of the exhibition, detailing works by John T. Riddle Jr., Betye Saar. and Spencer Cheney, the latter of whom was incarcerated at the time of the exhibition.

Jenkins pushed his relationship to the video form further as a performer and artist with Inconsequential Doggerel (1981), a fever dream that deconstructs a standard narrative structure by doubling down on image and sonic repetition to disrupt linearity and subjectivity.

In a conversation on the occasion of his first major retrospective, “Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation,” Jenkins told us about how then-new technology facilitated his shift into video and performance, the influence of films on this work, and his identification as a griot.

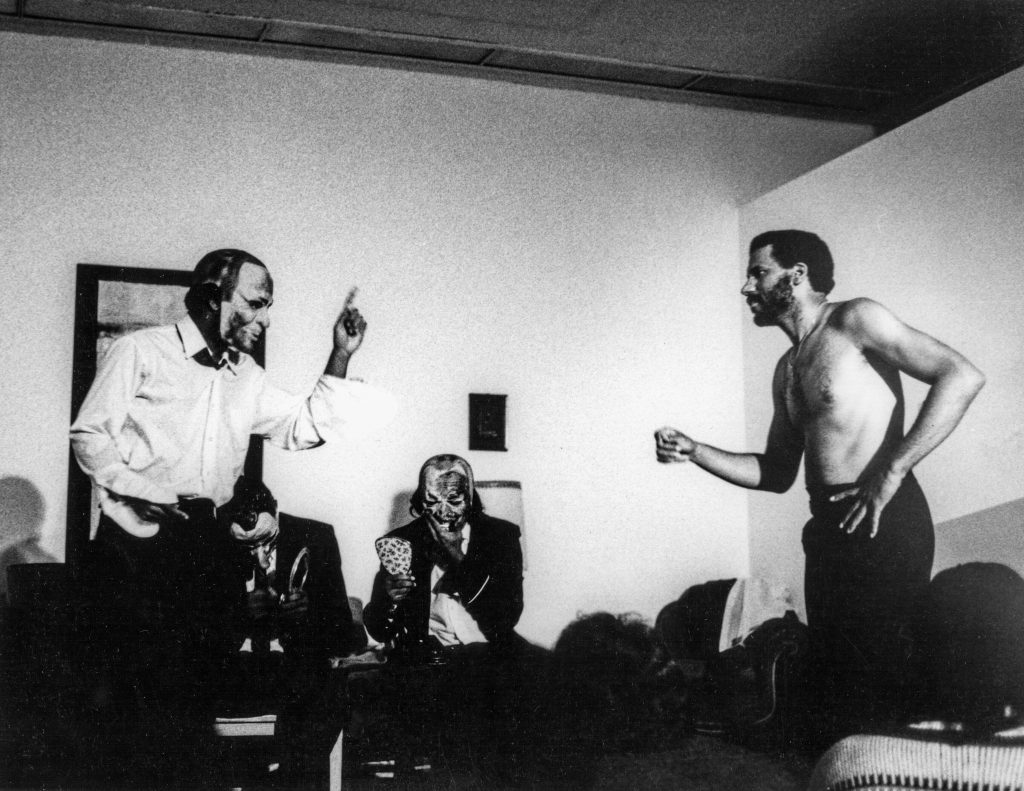

Ulysses Jenkins, Two Zone Transfer (1979), video still. Courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix.

Can you talk about your move from muralism and painting to performance, video, and an interdisciplinary practice?

The early ‘70s and the late ‘60s were the beginning of the independent film movement. Because of that, I was influenced by two films—Easy Rider and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song—and the type of social and political activities that were constructed in those films.

When I was painting a mural in Venice, Rat Trap, I got asked by a good friend of mine, Michael Zingale [if I would] be interested in his video workshop on the boardwalk in Venice. At first, I said, Well, what do I need that for? But my curiosity got the best of me, so I went down and started checking out that workshop and got something we figuratively called the “Video Jones”—getting attached to the equipment and technology. This was a brand new technology at that time, Sony’s Portapak. You could go to the workshop and check out the Portapak for a few days, and in those few days, you got really attached to your capability to record, erase, re-record, play back instantaneously. That was a marvel.

The work you did with Video Venice News and Remnants of the Watts Festival had a community-reporting orientation. But eventually, you really identified with, and identified yourself as, a griot character. What empowered you to take on that kind of role?

When I was at Otis [College of Art and Design] and I was in graduate school, the Caucasian grads kept telling me, “You’re not gonna be anything doing that Black shit.” And I said, What? I mean, how could you even say that? In an institution that has Charles White, that has Betye Saar. Myself, Kerry [James] Marshall, Greg Pitts, Ronnie Nichols—these are all the guys who are in Two Zone Transfer—were all studying with Charlie. And I’m seeing these two happened also at the time to be the only two African American art professors in L.A. A lot of people don’t quite understand the importance and the variance they brought, not only to the school, but to the Black community, and especially the Black arts community.

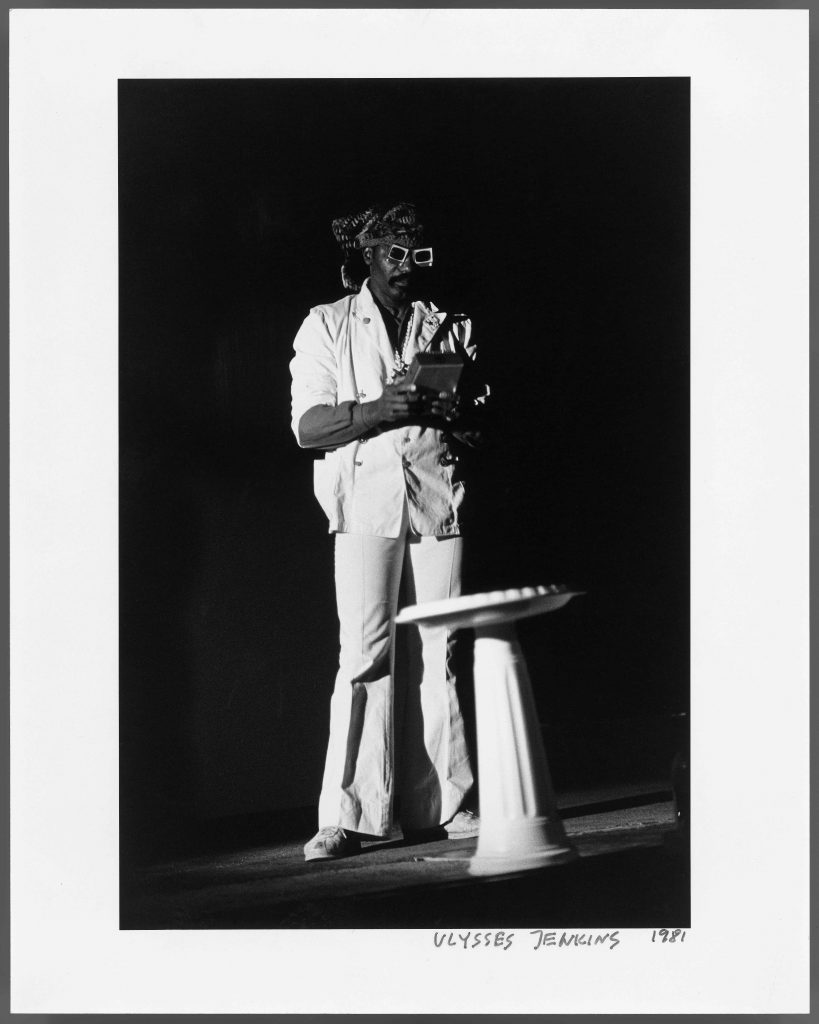

I didn’t realize at the time that I did Mass of Images, which was prior to Remnants of the Watts Festival and Two Zone Transfer, that I was actually already doing the griot. The griot was a storyteller for culture, for family events, religious events. In Africa, it was the person who came to the village and spread the news. So once I understood that, I realized that if I was going to keep doing performance, I needed a character. I needed a character that I could not only be proud of, but [that] could be representative. I think a lot of young artists may not understand that we have to separate ourselves, to an identity that we can feel proud of. That’s what being an actor really is. You’re portraying something that somebody else has written. I started to actually be able to construct a methodology that would work for me as an African American artist that I could claim as my own. I felt that I could “represent” as a griot.

Ulysses Jenkins, Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem (1979). Performance at Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Nancy Buchanan.

I want to take it back a bit to your time studying under Charles White and Betye Saar. In your memoir, Doggerel Life, you mention that Saar “took me through the depth of my cultural being.” You went to college as an undergrad in the South and then came back to California, which I imagine left an impression on you. Can you talk more about what you were learning and what you were dealing with internally?

[With Betye], the whole idea was, How do you perceive our culture from [an internal] point of view? Not many, if any, people were teaching that. To that extent, Betye was espousing that kind of expression in her work, and asking if you can identify with your own culture via the rituals that she’s presenting in her work. I think that’s the power you get spending time with her work.

If you see the Remnants of the Watts Festival video, there’s a piece of Betye’s that’s in the exhibition section. That particular exhibition was at the time one of the few and only places where African American artists in L.A. could show their work to the public. I was fortunate enough to actually exhibit a painting of myself in the nude, standing in the middle of the road, giving the finger. My angry Black man thing.

Well, we all have it in us.

My mom didn’t want it in her house.

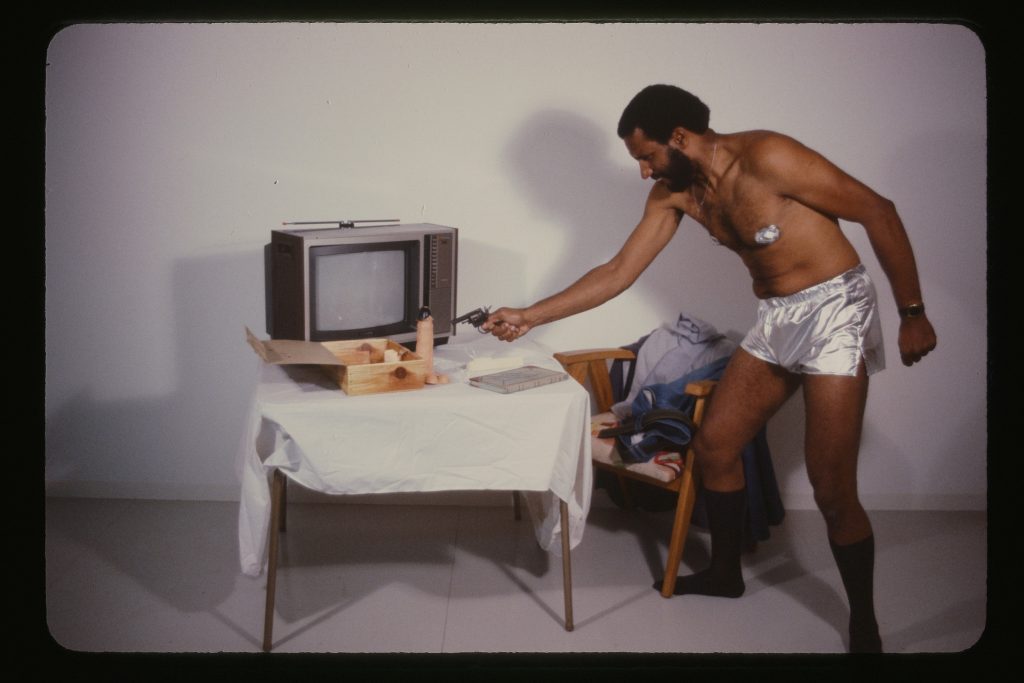

Ulysses Jenkins, Peace and Anwar Sadat performance documentation (1985). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: BASIA

I love that there’s this theme of diasporic traveling in your work and the ways in which you actualize this traveling through space and time through the context of video, whether in performance-oriented works like the 24-hour happening Dream City and the resulting video of the same name, or in the Video Griots Trilogy, connecting the Black diaspora and Indigenous people. You use time and duration and the traversing of space in both literal and symbolic ways.

I appreciate your comment. First and foremost, people tend to think that we as Black people don’t have anything else to say but what’s happening in the hood. I wanted to break away from that particular notion or construct. So I started making those videos here in L.A., such as Self Divination. That theme continues through [the Video Griots Trilogy] with Mutual Native Duplex and The Nomadics.

In each one of those, I am also exploring different technical processes that go along with how I make those videos. Getting back to the griot concept, I’m extending that process in terms of the ways in which I can actually express the message of the griot. When you get to The Nomadics, the narrative is not spoken per se. There are songs, there are melodies, and music from those cultures. When you see The Nomadics, as the soundtrack changes, so do the cultures.

I’m at a point where I have to actually explain what I’m doing. People tend to just look at video like it’s television. How do you get people to try to venture further into what they’re looking at?

Ulysses Jenkins, Without Your Interpretation rehearsal documentation (1984). Courtesy of the artist.

I think it’s very clear that you’re playing with the mediation of images. Not just what they’re communicating, but how they’re communicating, as well as playing with form. But yes, in 2022, to watch this much video work is also an exercise in thinking about how image-making has impacted how we see the world and how that has evolved with the coming of the digital age.

Well, I get all of that from my painting background. I was fortunate enough to meet Nam June Paik. I had been studying his work as well. I always thought that Nam June was painting, but with video. When he started doing a lot of chroma key [green screen], that is what I was also trying to do, especially with Inconsequential Doggerel.

It is similar to the process of printmaking. I knew that if it were to last, the video would have to be copied. And in making a copy, you lose resolution. So I figured every time that video was reproduced, it would be a new video. Colors would change, electronics would also change. In a sense, what you see today is just a new version of that video, based on the utilization of the technology.

“Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation“ is on view at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles until May 15, 2022.

Ulysses Jenkins, Dream City (1983). Courtesy of the artist and the Hammer Museum.