Art & Tech

An Underwater Sculpture Park Coming to Miami Beach Is a Stark Warning About What Climate Change May Bring

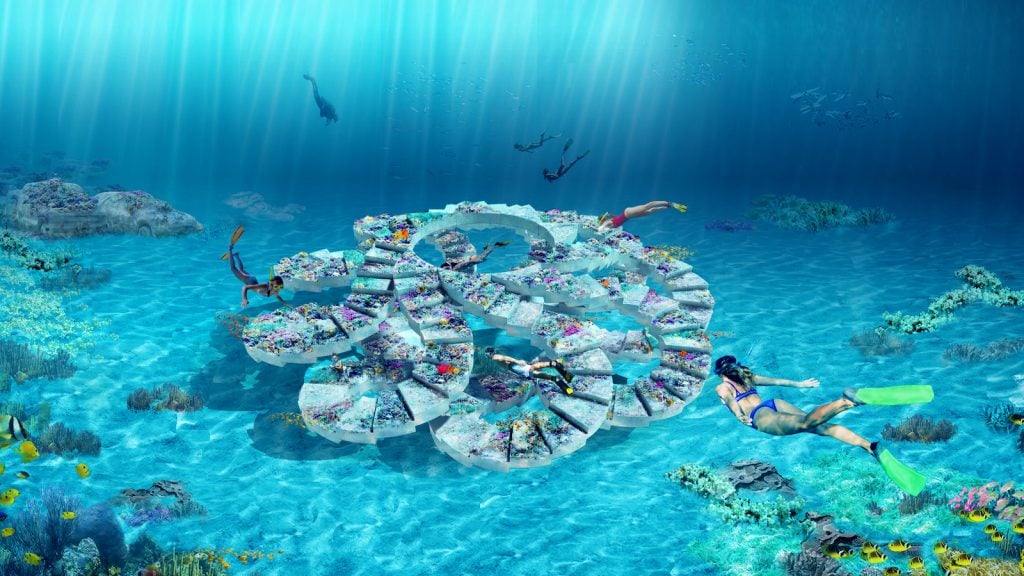

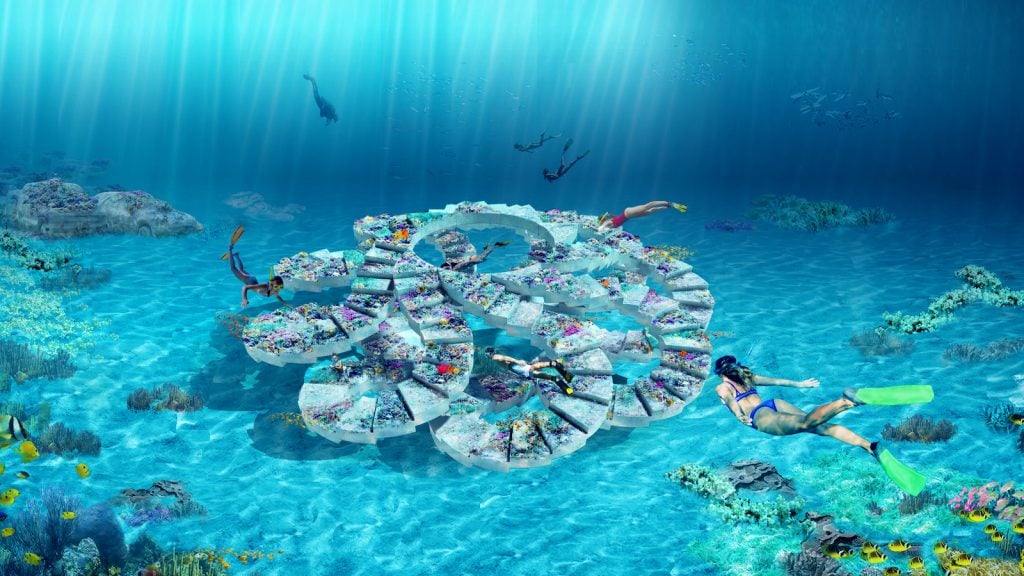

The underwater sculptures will form a kind of reef to help regrow damaged coral.

The underwater sculptures will form a kind of reef to help regrow damaged coral.

Brian Boucher

By the end of 2021, visitors to Miami Beach will have a new cultural attraction to check out—on the ocean floor.

Artists, architects, scientists, preservationists, and city officials are coming together to create an underwater sculpture garden that will form an artificial reef, helping to foster the regrowth of the area’s destroyed coral and serving as a breakwater to protect the beaches from storms. When the project is complete, the seven-mile ReefLine facility will provide a place for snorkelers to experience artworks by Leandro Erlich, Ernesto Neto, and Agustina Woodgate.

Shohei Shigematsu, of Rem Koolhaas’s Rotterdam-based architecture firm OMA, is heading up the master plan as well contributing his own large-scale underwater sculpture.

“Many cities have artificial reefs,” Ximena Caminos, founder of BlueLab Preservation Society and the project’s artistic director, told Artnet News. “The secret ingredient here is the arts, but it’s crucial that this is artist-designed and scientist-informed. We need the city and the scientists and the philanthropists.” Indeed, the list of participants and supporters is long: University of Miami researchers join BlueLab and Coral Morphologic (marine biologist Colin Foord and musician JD McKay) on the project, with the support of the city, the Knight Foundation, the Blavatnik Family Foundation, and the XPRIZE Foundation.

“Miami Beach has a world-renowned environment and beaches, and has in recent years established itself as a true international arts and culture destination,” said Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber in an email, “so we are excited to welcome this resilient, unique project and continue collaborating with the best of the scientific and artistic community to elevate our community.”

Leandro Erlich, Concrete Coral. Courtesy the artist.

Erlich’s project, Concrete Coral, makes a direct commentary on climate change. He will place sculptures of cars—among the worst culprits in global warming—on the ocean floor, transforming them into devices to mitigate the effects of ocean warming on the coastal city. (Last year, Caminos organized Erlich’s “traffic jam” of life-size sand sculptures of cars in Miami Beach.)

Erlich’s sense of scale, Caminos said, is part of what appealed to her for this project, as well as the fact that his work operates, pardon the pun, on different levels. “His works have the depth of a beautiful metaphor,” she said, “but they’re always a bit sneaky.”

The cars in Erlich’s traffic jam project “were so stunning, it was natural for them to have an afterlife,” Caminos said. “If we don’t solve this, the cities will end up underwater. Cars on the ocean floor becomes a vision of what the future could look like if we don’t work together.”