Art & Exhibitions

Urban Justice Center Turns Art into a Weapon for Social Change

Art can be a powerful tool for social advocacy.

Art can be a powerful tool for social advocacy.

Sarah Cascone

Formerly incarcerated men participating in Gregory Sale’s “Rap Sheet to Resume” at the Urban Justice Center.

Photo: screenshot from video produced by the Urban Justice Center.

What happens when art meets social justice? That’s what New York’s Urban Justice Center (UJC) looks to explore its its new series pairing advocacy work with art by socially engaged artists.

The series kicked off last week with an exhibition by Favianna Rodriguez and Gregory Sale that challenges viewers to question their preconceived notions about incarcerated people, minorities, migrants, and the poor, among other hot-button topics.

“Art is a way to resensitize the way we think about tough and complex issues,” explained exhibition curator and artist Marisa Morán Jahn during a tour of the show.

Rodriguez’s series “The Art of Disruption” is based on her own experience growing up in Oakland as a Latina immigrant with both African and Asian heritage.

Favianna Rodriguez works on a piece in support of migrants for the Urban Justice Center.

“We tend to put people in these boxes,” Rodriguez said during the opening. “We have to look at the humanity, the true, complex experience of people of color.”

In one painting, the monarch butterfly, a migratory species, stands as a symbol of migrants. “Migration is a part of the human experience,” Rodriguez explained of the work, which she hopes will “challenge implicit bias” against migrants.

Another work quotes feminist thinker Emma Goldman: “If I can’t dance I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” For Rodriguez, the fight for social change should be uplifting. She fears that “we are stuck in pain-oriented narratives, instead of celebrating and feeling joy.”

Formerly incarcerated individuals participating in Gregory Sale’s “Rap Sheet to Resume” at the Urban Justice Center.

Photo: screenshot from video produced by the Urban Justice Center.

Sale, for his part, has spent the last ten years working with individuals who have been impacted by incarceration. At the UJC, he was able work with 14 former inmates, as well as Susan Goodwillie, a social worker, and Johnny Perez, a reentry specialist for the center, on the project “Rap Sheet to Resume.”

“Rap Sheet to Resume” was conceived as a way to help those released from prison with the struggle of reentry and reintegration. “As more and more people are released, what are we doing to support them?” asked Sale.

The workshop was both a creative outlet and a practical exercise designed to help the former inmates identify their transferable skills and communicate them on paper for potential employers.

Favianna Rodriguez, I Am An Onion With Many Layers To Peel.

Photo: Favianna Rodriguez.

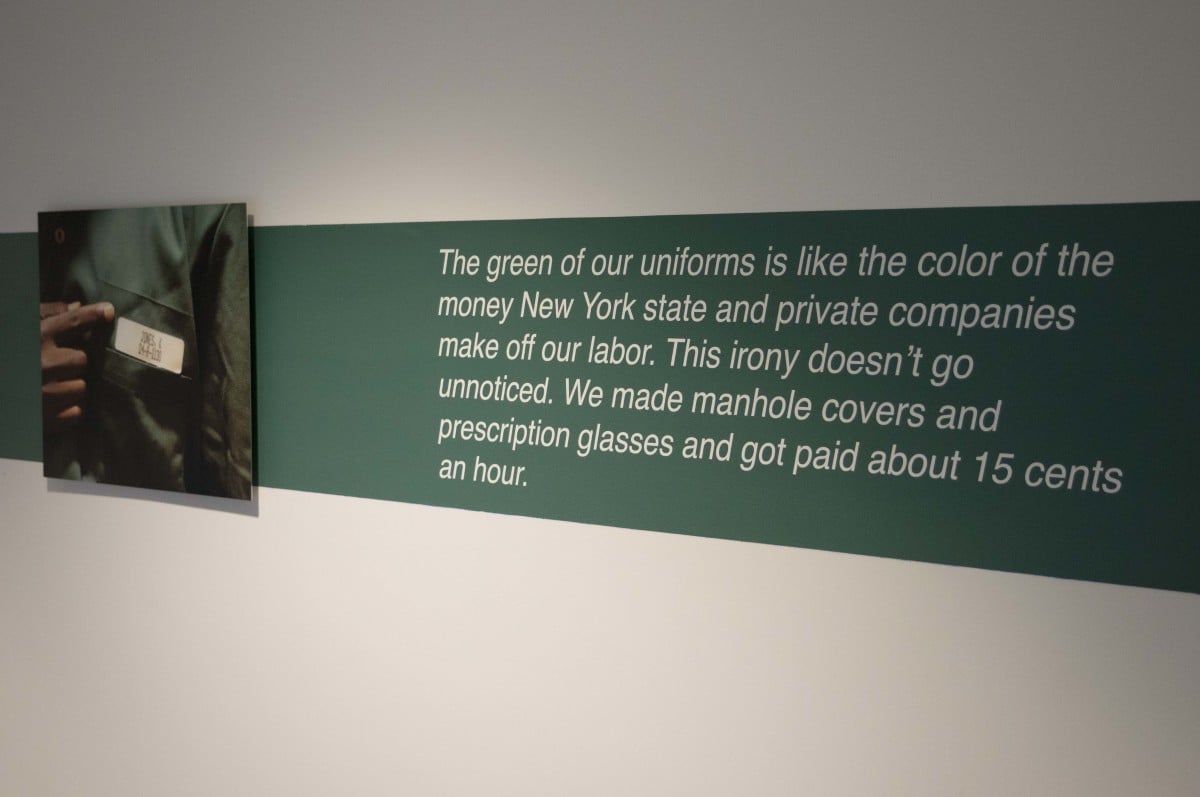

Reflecting on their time behind bars, the participants selected a drab green color reminiscent of prison jumpsuits to represent their former lives, and a hopeful sky blue to reflect their dreams for the future. The two colors are painted on the walls of an UJC hallway in a site specific work.

“There is a change I see happening where people are starting to realize that those of us who have criminal histories can do a lot of good,” reads a quote on the wall from participant Emmanuel Kelly. “I hope that people will give us a chance. Actually I see it coming, because doors are opening for us.”

Gregory Sale, installation for “Rap Sheet to Resume” at the Urban Justice Center in New York. Photo: Jason Dillon, courtesy Gregory Sale.

Prison reform is indeed gaining steady support, with President Barack Obama calling on federal agencies to “ban the box” that forces former inmates to disclose their criminal convictions on job applications.

Sales also presents “Life Is Life,” works he created with 10 prisoners sentenced to life behind bars without parole. The participants wrote their life stories, beliefs, regrets, and even their own obituaries, which became the basis for the works on view.

“They wanted people to think twice about how they were locked up and the key was thrown away,” said Sale. “America’s waking up to how broken the system is.”

The exhibition of work by Favianna Rodriguez and Gregory Sale is on view at the Urban Justice Center, 40 Rector Street, ninth floor, New York, October 29, 2015–February 26, 2016.