Art World

Urs Fischer on His Miami Bus Stop, His Team-up With Katy Perry, and the ‘Most Difficult’ Project of His Life

His spooky new Miami installation, Bus Stop, has people talking.

His spooky new Miami installation, Bus Stop, has people talking.

Rachel Corbett

About every 30 seconds someone passing through Paradise Plaza, the new outdoor shopping area in Miami’s Design District, pauses in front of a bus stop, smiles, and pulls out a phone to take a picture. It’s a typical Miami Beach bus shelter—except for the fact that it is occupied by a skeleton dramatically sprawled across the bench, with a steady drip of water hitting its forehead and pooling into a puddle on the ground. A blank white advertising light box glows on one side.

This work, titled Bus Stop, is sure to have people talking as crowds flood into Miami for fair week, and it is the work of artist Urs Fischer. We spoke to him about the unusual inspiration for the new installation, as well as his recent collaboration with Katy Perry, and why working on his upcoming show in New York has been “the most difficult thing I’ve ever done in my entire life.”

Urs Fischer, Bus Stop (2017). Image courtesy Urs Fischer.

A lot of your work erodes or changes over time. Will the water affect the skeleton here?

No, because it’s bronze. It was carved in styrofoam and arranged, then cast in bronze. But it will get green or brown over time, and probably will start to show the residue in the window.

How did you come to this location?

Through [the developer] Craig Robins. He just opened this whole area, these stores are just temporary, the restaurants. He asked me if I would make a sculpture for this plaza and I said sure. So I made it and now it’s here. This is kind of like the design of a Miami Beach bus stop. It’s a bit reversed and it’s reduced, but it’s a stylized version of a Miami bus stop.

You make a lot of portraits of recognizable figures, including your own collectors. Why are you also drawn to skeletons, which are completely anonymous?

I’ve made skeletons for about 17 years, just not many. Every two years or so I’ll make one. Maybe the first one was in 2000. The skeleton is anonymous so you don’t get trapped in personalities, gender, and age. It’s very reduced. You don’t have a lot of stuff. It’s a portrait or figure with no information, and that’s what’s good about it. But this skeleton is also really animated, it’s not turning away from anything.

You’ve also done fountains before, but they were much more elaborate than this one.

[The ones at Gagosian Los Angeles] were like jets. The fountains I made there were the first ones. Fountains are—I don’t know what fountains are. But they’re alive in some way, they’re an activating thing. A fountain is always a little bit of life, a signifier of life somehow. It’s kind of like how ecstasy and agony are twins, high and low are twins.

The indentation on the ground was made. We designed the shape of the puddle, so there’s overflow there by design. It’s not just a random thing. The pooling is part of the fountain.

Urs Fischer’s new installation, Bus Stop (2017). Image: Rachel Corbett.

What were you thinking about when you made this work?

Actually with this work I was thinking about Edward Hopper. With Hopper you always have this particular space, even when it’s the countryside, you have the house or room or empty rooms; urban scenes, the diner, the people who stand on porches alone or two people that don’t talk, people that kiss. There’s also usually artificial light—either sunlight or artificial light. It’s just a room and sunlight.

Also, the figures operate on the stage in Hopper. There’s always this kind of emptiness, this void and a certain kind of sentiment that comes with it. We know this feeling, we understand this sentiment.

Here, for me, there’s a certain kind of night light in the reflection and glass and water. It’s almost like you’re walking underneath scaffolding in New York and there’s this grimy moment in the water, a certain uncontrolledness, a splash, the trash in the puddle. I like that.

You also have a work up now in New York, a giant clay bust of Katy Perry that anyone can come and alter. How did that collaboration come about?

Katy asked me to do something for her album release, Witness.

For the cover?

No, it was this whole thing, like a Big Brother thing where she was in a container and they wanted to have different songs, different artists and this and that. She wanted to have a station per song in this open warehouse with lots of space, but then logically it was more of an event type space and it got more complicated.

So I said, “OK, let’s do this: I have this idea for the plasticine thing,” and I said, “You pick the pose.” And she said she wants to be naked and we started scanning the next day for that but it’s technically too complicated to have the whole figure, the armature as well. So then I just reduced it to [a bust] because it does the same thing, it feels naked. It’s exposed. Her head’s up and eyes closed, she’s vulnerable and open.

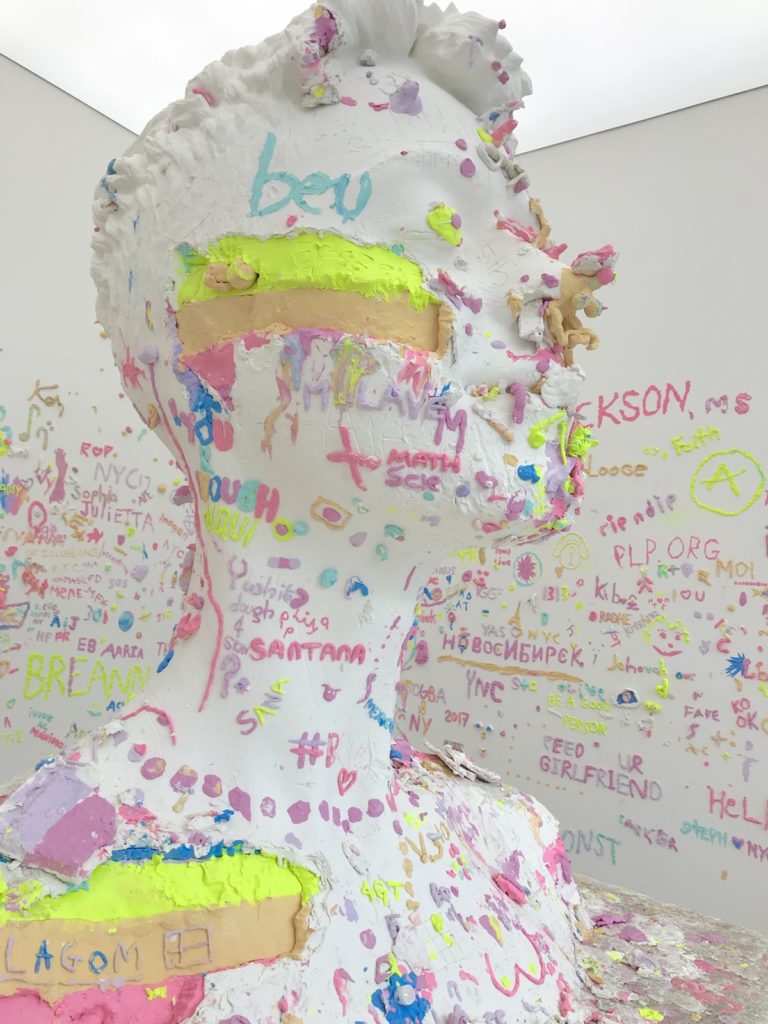

Urs Fischer’s Bliss (2017). © Urs Fischer. Courtesy of the artist.

Why was the full figure too complicated?

In sculpture, if you look at something that’s static you need to idealize it. You scan, then you need to make up how her breasts look, and so on, and it just gets complicated. You just don’t want to deal with it. You could deal with it but then it becomes a real commitment to get things right. You can, but there was no time to do that. We had four or five weeks. We tried to make it happen but I said we can make something else that’s good in this time. And then I had it in my studio a month or two later and I thought we should use it for something. It’s a piece. I’m happy for it to go somewhere so it’s not a waste.

In the beginning, it was very pristine. Then it has gradually deteriorated into neurotic contemporary urban folk art. The colors look so crazy. It drifts away into something that’s just anybody’s. At all times we have around 20 people in there, we have so many people in there. That’s why I rented this pop-up store. I like that there is a place where you cannot buy anything, it’s mainly people who don’t have anything to do with art. They’re tourists, kids, lots of selfies.

Did Katy have any feelings about her own likeness being defaced?

That’s probably what her life feels like anyway. Everybody takes a piece and it erodes and builds into its own reality.

What else do you have coming up?

I have some cool stuff coming up. I’m working on a bunch of shows for May, in New York, Chelsea.

At Gagosian?

If it all works out, yes. We’ve been working on it for a year and a half. Each space has, if it works out, one work in it. It’s very reduced.

So you will show in the galleries simultaneously?

If it works out. It’s extremely simple but it’s the most difficult thing I’ve ever done in my entire life besides marriage and divorce and raising children.