Law & Politics

An Appeals Court Rules That Andy Warhol Violated a Photographer’s Copyright by Using Her Image of Prince Without Credit

The Andy Warhol Foundation plans to appeal.

The Andy Warhol Foundation plans to appeal.

Sarah Cascone

Celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith has won her copyright lawsuit against the Andy Warhol Foundation on appeal.

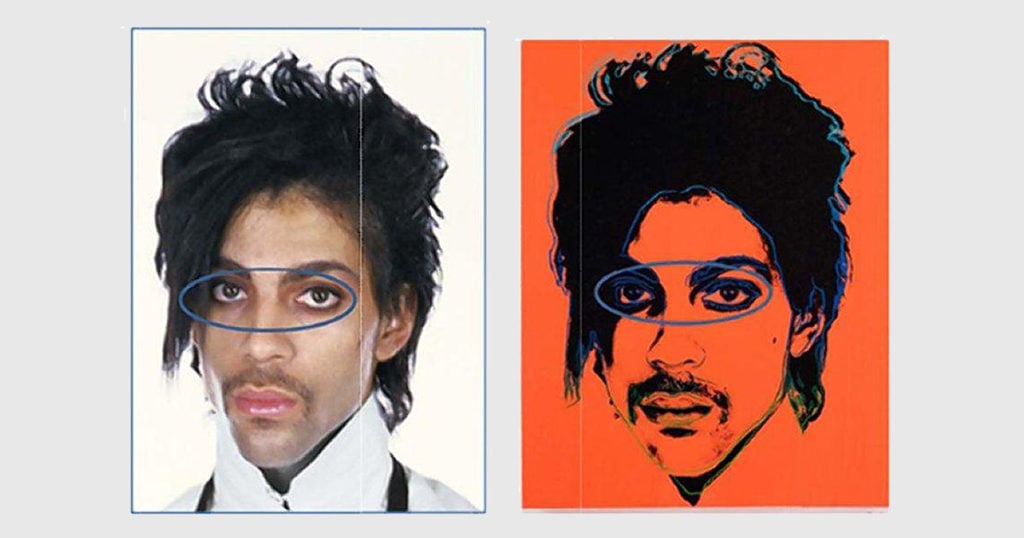

The 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals reversed a 2019 ruling from New York’s federal court finding that Andy Warhol had made fair use of Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince when he created the “Prince Series.” Goldsmith appealed that verdict, arguing that the Warhol artworks were not a transformative use of her image.

“We agree,” judge Gerard E. Lynch wrote. “The Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law.”

The Warhol Foundation plans to appeal the ruling, reports ARTnews.

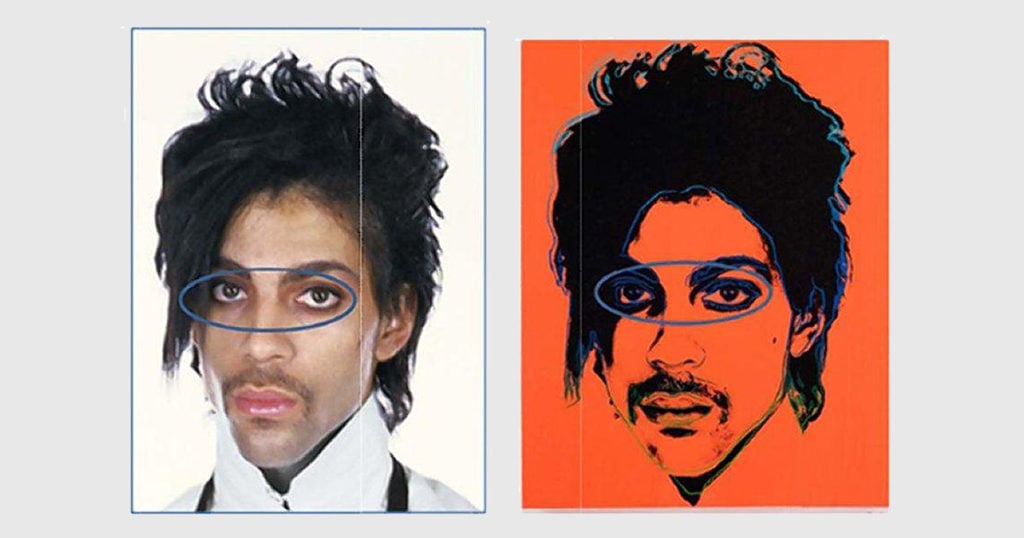

Andy Warhol’s Prince illustration based on the Lynn Goldsmith photograph as it appeared in Vanity Fair, here reproduced in court documents.

The lower court had cited the circuit court’s 2013 ruling in Cariou v. Prince, which controversially found that appropriation artist Richard Prince had not violated Patrick Cariou’s copyright by altering photos from Cariou’s 2000 book, Yes, Rasta, for the 2008 series “Canal Zone.” (Cariou appealed the verdict, and the two artists eventually settled out of court.)

“It does not follow, however, that any secondary work that adds a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material is necessarily transformative,” the circuit court said in the Goldsmith appeal, saying it found that the “Prince Series” is likely legally derivative, and that both artworks serve the same function as a portrait of the singer.

In the earlier verdict, judge John G. Koeltl found the Warhol images were fair ise because they transformed a “vulnerable, uncomfortable person” in Goldsmith’s original photograph into “an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

“That was error,” Lynch wrote. “The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.”

To be a transformative use, he added, the new work must offer “something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work.” He compared Warhol’s distinctive silkscreen aesthetic to filmmaker with an easily identifiable style turning a book into a movie—that doesn’t mean the film is no longer a derivative work.

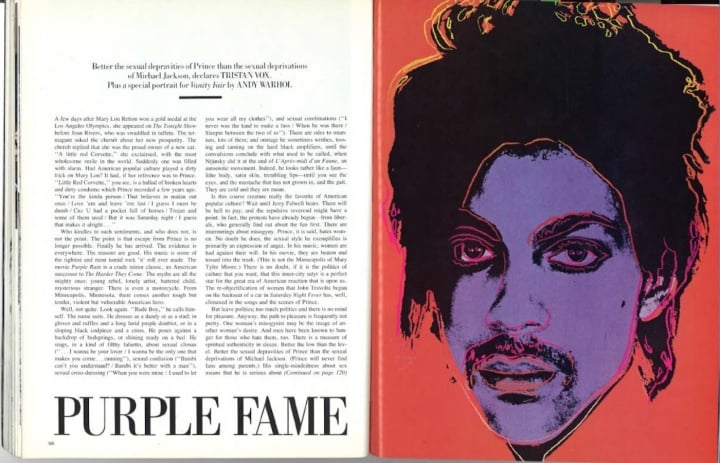

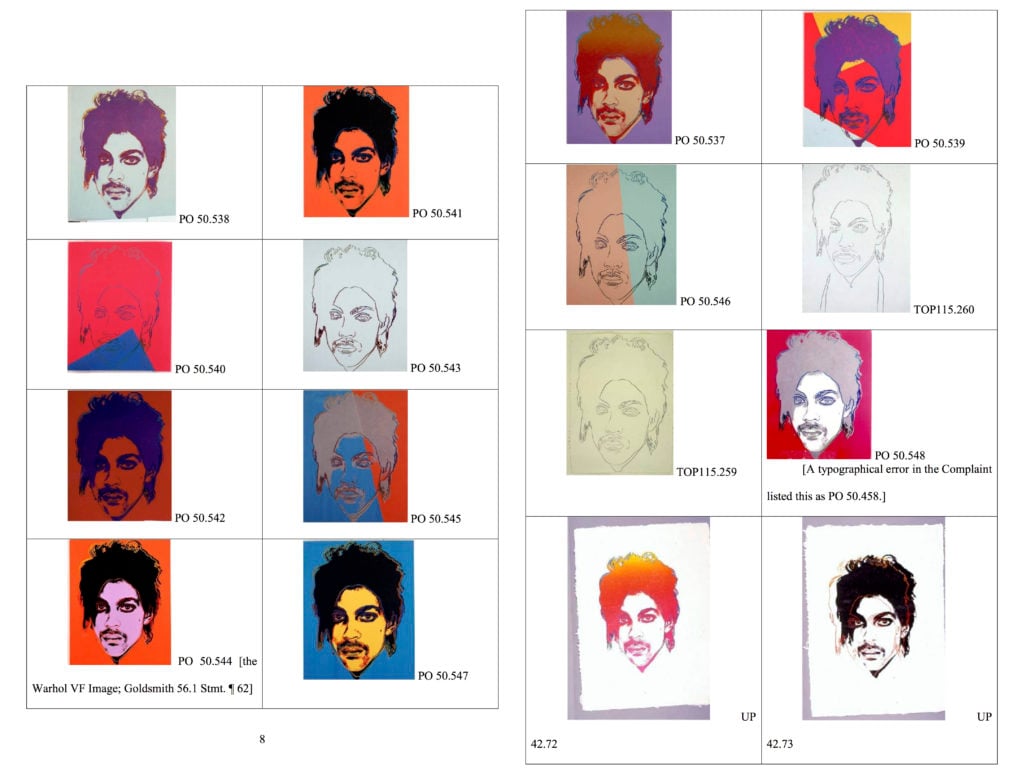

Andy Warhol’s ‘Prince Series,’ as reproduced in court documents.

“Over fifty years of established art history and popular consensus confirms that Andy Warhol is one of the most transformative artists of the 20th century,” the foundation’s lawyer, Luke Nikas, told Artnet News in an email. “While the Warhol Foundation strongly disagrees with the Second Circuit’s ruling, it does not change this fact, nor does it change the impact of Andy Warhol’s work on history.”

In 1981, Goldsmith had a photoshoot with Prince while on assignment for Newsweek, but the images were never published. In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one of her portraits of the singer for artistic use for an illustration commissioned from Warhol. The artist ultimately made 16 works based on the photo—but Goldsmith only learned about them in 2016, after Vanity Fair republished the artworks after Prince’s death, without crediting her.

The Andy Warhol Foundation drew first blood in the ensuing legal battle, filing a pre-emptive lawsuit in April 2017 asking the court for a declaratory judgment stating that the “Prince Series” did not violate Goldsmith’s copyright. A countersuit from the photographer soon followed.