Art & Exhibitions

An Arles Exhibition Unpacks Van Gogh’s Deep Fascination With the Night Sky

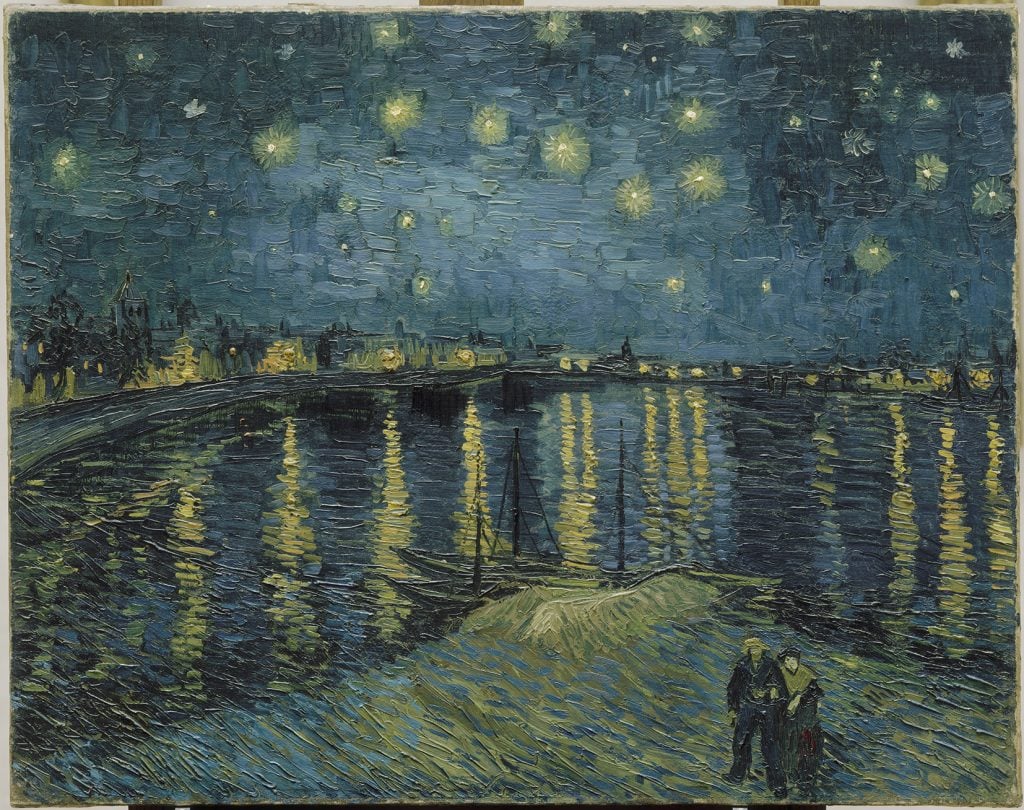

"Starry Night Over the Rhône," Van Gogh's famed nightscape, returns to its city of origin after more than a century.

Van Gogh arrived in Arles, France, in 1888, eager to escape the bustle of Paris. Installed in the Yellow House on Place Lamartine, he found some measure of peace: “There are some really beautiful nights here,” he wrote to painter Émile Bernard. Here, he commenced his most prolific period, painting the city’s wheat fields and street side cafes in golden hues. But he also gazed upward. “A starry night,” he told Bernard, “is something I should like to try to do.”

In September, Van Gogh created Starry Night Over the Rhône, depicting a star-spangled night sky reflected in a beautifully textured body of water. “On the aquamarine field of the sky the Great Bear is a sparkling green and pink, whose discreet paleness contrasts with the brutal gold of the gas,” he described the work in a letter to his brother Theo. “Two small colored figures of lovers in the foreground.”

Installation view of “Van Gogh and the Stars” at Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles. Photo: François Deladerrière.

A new exhibition at Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles is now further illuminating the celebrated Rhône nightscape, which predates the painter’s most well-known composition, The Starry Night (1889). “Van Gogh and the Stars” sees his Arles canvas return to its city of origin after more than a century (it’s in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris) to better explore its scientific, literary, and personal context.

Van Gogh, famously, had a thing for the night sky—from its array of celestial bodies to its depth of hue. His fascination was driven by his observations and surprisingly, his faith: in a letter, he confessed to Theo a “tremendous need for, shall I say the word—for religion—so I go outside at night to paint the stars.”

Camille Corot, L’Étoile du Berger (Evening star, morning star) (1864). Photo: Daniel Martin, courtesy of Mairie de Toulouse, Musée des Augustins.

The 19th-century milieu, which saw well-publicized leaps in astronomy and the growth of science fiction, likely also spurred Van Gogh’s interest and research into the upper spheres, too. Included in the show are works by scientific illustrators such as Étienne Léopold Trouvelot and Lord Ross, and other research that captivated the public at that time.

Starry Night won’t be the only nocturnal scene on view at the show, though. “Van Gogh and the Stars” also traces how his preoccupation with constellations has colored art history through the work of more than 76 other artists.

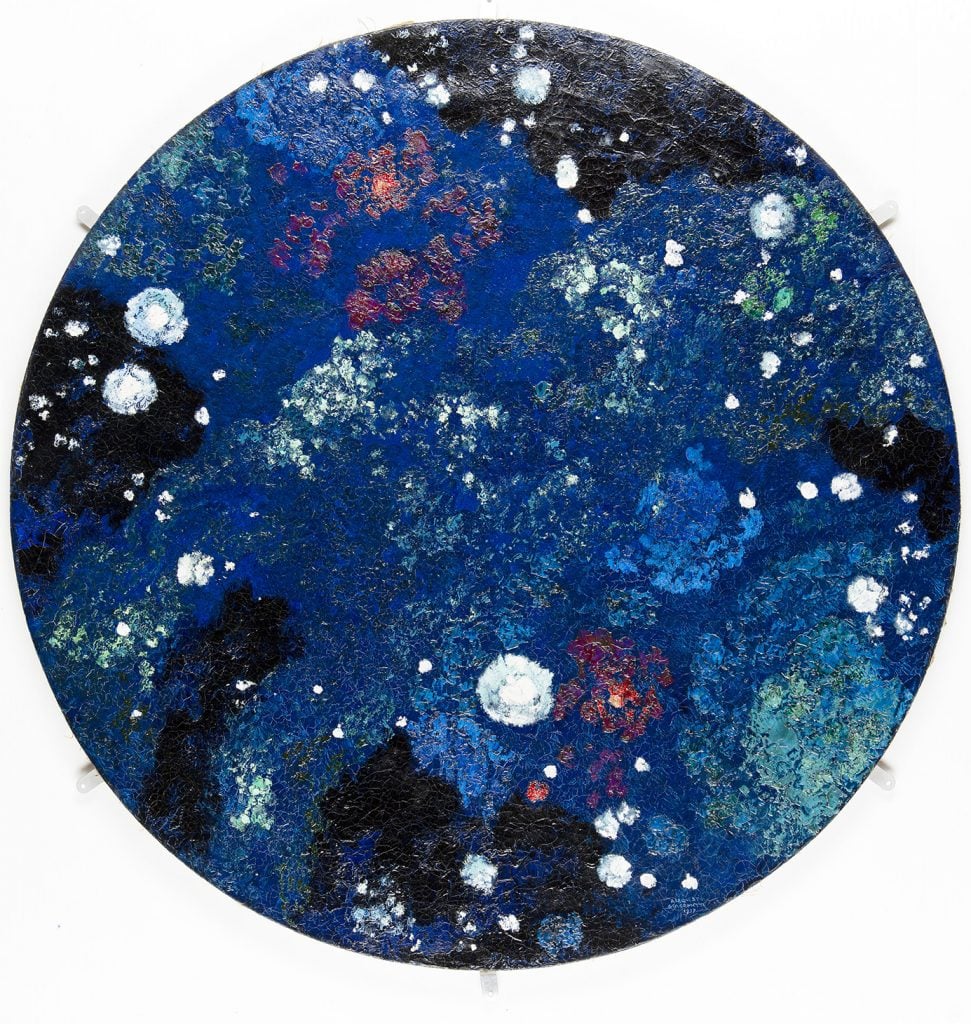

Augusto Giacometti, Sternenhimmel (Milchstrasse) Starry night (1917). Photo: Bündner Kunstmuseum

Chur, Thomas Strub.

Subsequent paintings by artists as varied as Edvard Munch, Helen Frankenthaler, Paul Klee, Robert Delaunay, and Kasimir Malevich are featured here to highlight their own reading of the stars. Augusto Giacometti’s Sternenhimmel (Milchstrasse) Starry night (1917) offers an abstract yet profoundly moving glimpse of the night sky, while Georgia O’Keeffe’s Starlight Night, Lake George (1922) presents a placid view echoing Van Gogh’s reflective Rhône River.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Starlight Night, Lake George (1922). Photo courtesy of Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles.

Van Gogh’s belief that the stars held the key to the afterlife—a belief that emerged from the era’s para-scientific literature—is also paralleled in the works of his creative peers. The show gathers the works of his contemporaries including James Ensor, Odilon Redon, and Constantin Ciurlionis, which reach for metaphysical dimensions.

Paul Mignard, Prémonition (2024), on view at “Van Gogh and the Stars” at Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles. Photo: François Deladerrière.

Even today, the night sky continues to hold fascination for contemporary artists from Anselm Kiefer and Tony Cragg to Alicja Kwade and Dove Allouche, whose pieces also show up here. (A new multi-sensory installation by Amsterdam-based collective DRIFT, commissioned by the museum to run alongside the exhibition, further explores Van Gogh’s grasp of visible and invisible nature.)

“I often think that the night is more alive and more richly colored than the day,” Van Gogh once mused. His perspective, it turns out, was unerring.

“Van Gogh and the Stars” is on view at Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles, 35 Rue du Dr Fanton, 13200 Arles, France, through September 8.