Art World

Vincent van Gogh Was Definitely Crazy, but Doctors Aren’t Sure Why

One author blames foxglove in a new book.

One author blames foxglove in a new book.

Sarah Cascone

Over 100 years after his death, today’s medical professionals agree that Vincent van Gogh suffered from psychosis, but they still aren’t sure why, reports the New York Times. Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum is currently holding an exhibition on the topic, called “On the Verge of Insanity” (through September 25), and brought together 35 doctors, psychiatrists, and art historians around the world to examine the evidence.

“It’s difficult to make a diagnosis, so the real progress we’ve made is that specialists in the field are talking about it, and they’ve never done this before,” University of Amsterdam art history professor Louis van Tilborgh, who is a researcher at the museum, told the Times. He characterized the debate over the artist’s diagnosis as “fierce.”

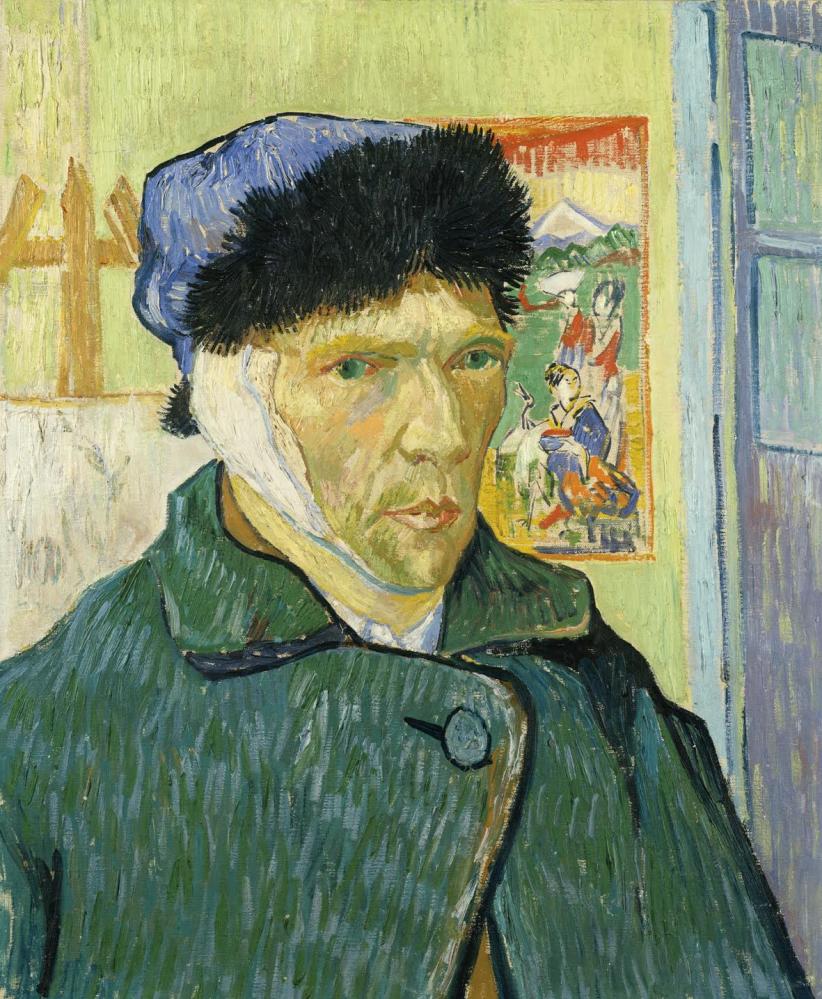

That’s because there are any number of potential causes that led Van Gogh to famously sever his own ear in 1888, and to kill himself two years later. Among the theories floated over the years are bipolar disorder, temporal lobe epilepsy, syphilis, borderline personality disorder, cycloid psychosis, and schizophrenia.

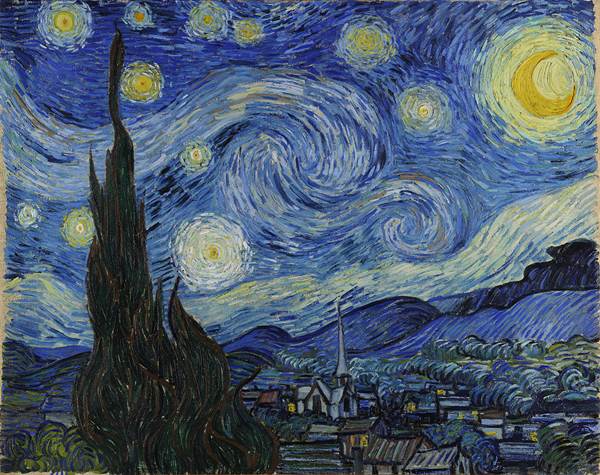

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889). Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art.

The two-day conference at the museum drew on Van Gogh’s many letters, art-historical information, and medical evidence to try and arrive at a diagnosis. The experts reportedly ruled out schizophrenia, because van Gogh suffered from short psychotic episodes, which he reflected upon in his letters afterward.

“He has repeated episodes of psychosis but recovered completely in between,” medical ethics professor Arko Oderwald told the Telegraph. He said the ear incident “could come from alcohol intoxication, lack of sleep, work stress and troubles with Gauguin, who was going to leave.” (The two artists were close friends, and Van Gogh had hoped that their living together would be the start of a larger artists’ colony.)

The experts were ultimately unable to definitively pin down the underlying cause of Van Gogh’s illness, which led to several extended stays at mental hospitals in his final years.

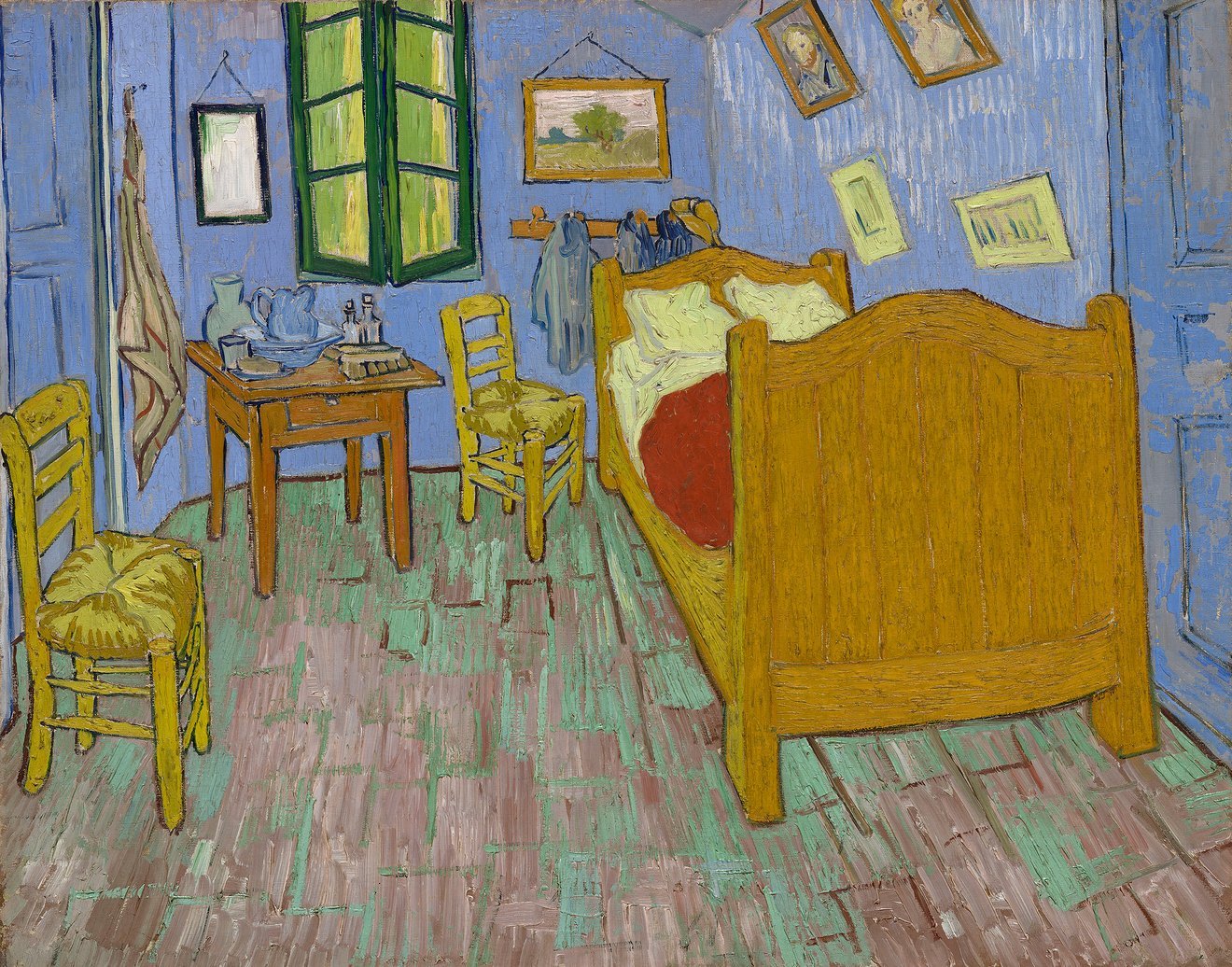

Vincent Van Gogh The Bedroom (1889). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“The essential symptoms for psychosis that we agreed on that he had were hallucinations, acoustic hallucinations, optical hallucinations and also delusions, hyper-excitation with confusional states, incoherent speech and unclear memory about the episodes,” explained Werner Strik, director of Bern, Switzerland’s, University Hospital of Psychiatry, to the Times.

In his forthcoming book Breaking Van Gogh, James Ottar Grundvig posits that Van Gogh’s mental decline can be attributed in part to foxglove, which was used as a remedy for mental health patients at the time, but that contains “a natural toxicity that affects the heart.” The medicine, taken “in concert with lead poisoning from the oil paints, along with his consumption of absinthe…” he wrote, “put Van Gogh on an accelerated destructive path that would lead to death.”

With all this in mind, Oderwald noted, “One single thing cannot explain the entire picture of what happened to Van Gogh.”