Art World

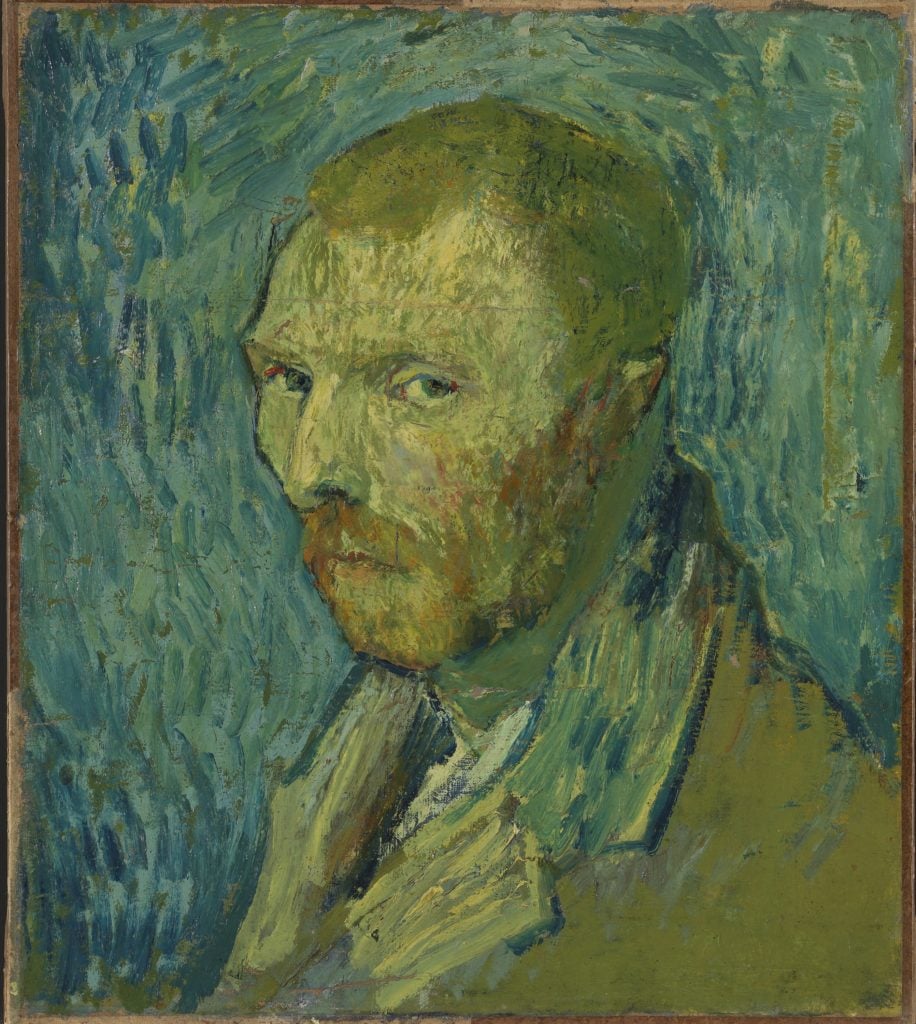

Experts Conclude That This Odd Self-Portrait of Vincent van Gogh Giving the Side Eye Really Is by the Dutch Master

The 1889 work was completed when the artist was in the throes of psychosis.

The 1889 work was completed when the artist was in the throes of psychosis.

Naomi Rea

Leading experts on Vincent van Gogh have concluded that a strange portrait belonging to a Norwegian museum is actually an authentic work by the Dutch master. Extensive research conducted by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has shown that the artist executed the unusual self-portrait while he was suffering from psychosis.

The painting, from 1889, has been in the collection of Oslo’s Nasjonalmuseet since 1910, but its attribution to Van Gogh has been openly disputed since 1970. Over the years, some scholars took issue with crucial missing provenance details, while others deemed its style and dreary color palette out of key with the rest of the artist’s oeuvre.

While provenance research carried out at the Najonalmuseet in 2006 showed that the work had belonged to two friends of Van Gogh, Joseph and Marie Gioux, who lived in Arles, it was still unclear when the couple received the work. And, for a long time, experts couldn’t agree on a date of execution, or whether it was done in Arles, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, or Auvers-sur-Oise.

In a bid to settle the matter once and for all, the museum invited the experts in Amsterdam to study the portrait in 2014. Now, after comprehensive inspection of its style, technique, material, and provenance, researchers have concluded that it is “unmistakeably” by Van Gogh’s hand.

The work turns out to be the only one that can be tied to a letter Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo on September 20, 1889. What’s more, the letter proves that the work is actually a significant one, executed while the artist was having his first major psychotic episode at an asylum in Saint-Rémy. In his letter, Van Gogh describes it as “an attempt from when I was ill.” It is the only known work painted by the artist when he was in the throes of psychosis.

“Although Van Gogh was frightened to admit at that point that he was in a similar state to his fellow residents at the asylum, he probably painted this portrait to reconcile himself with what he saw in the mirror: a person he did not wish to be, yet was,” Louis van Tilborgh, a senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum and an art historian at the University of Amsterdam, says in a statement. “This is part of what makes the painting so remarkable and even therapeutic.”

In mid-July of that year, Van Gogh entered a state of psychosis that lasted until September. At the end of the summer, in a letter dated August 22, he wrote that he was still “disturbed” but was well enough to experiment with painting again. This led experts to conclude that the work was done after August 22 but before September, and it therefore predates both of his famous 1889 self portraits in Washington’s National Gallery of Art and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

The work shows Van Gogh looking defeated, head slightly bowed and gazing sideways at the viewer with a lifeless expression. While the brownish-green pigments and somber palette seemed unusual for the artist who is known for his bright blues and yellows, the palette and brushwork are actually consistent with other works dating from the summer and autumn of 1889, which make sense within the context of the work’s execution.

The work is currently on view on the third floor of the Van Gogh Museum, and will be included in the museum’s upcoming exhibition of artists’s portraits, “In the Picture,” beginning February 21. After the exhibition closes in May, the work will return to Oslo where the Nasjonalmuseet is slated to reopen after renovations in 2021.