Art World

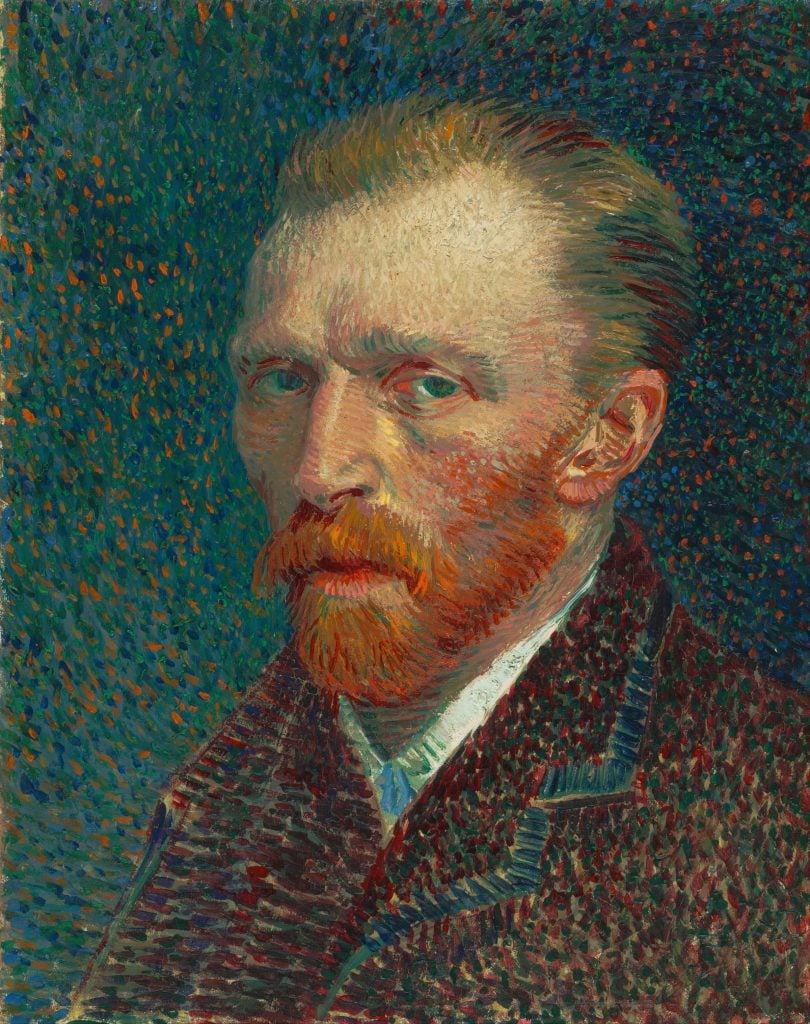

A New Book Reveals Vincent van Gogh and His Little Sister’s Powerfully Moving Correspondence About Their Struggles With Mental Health

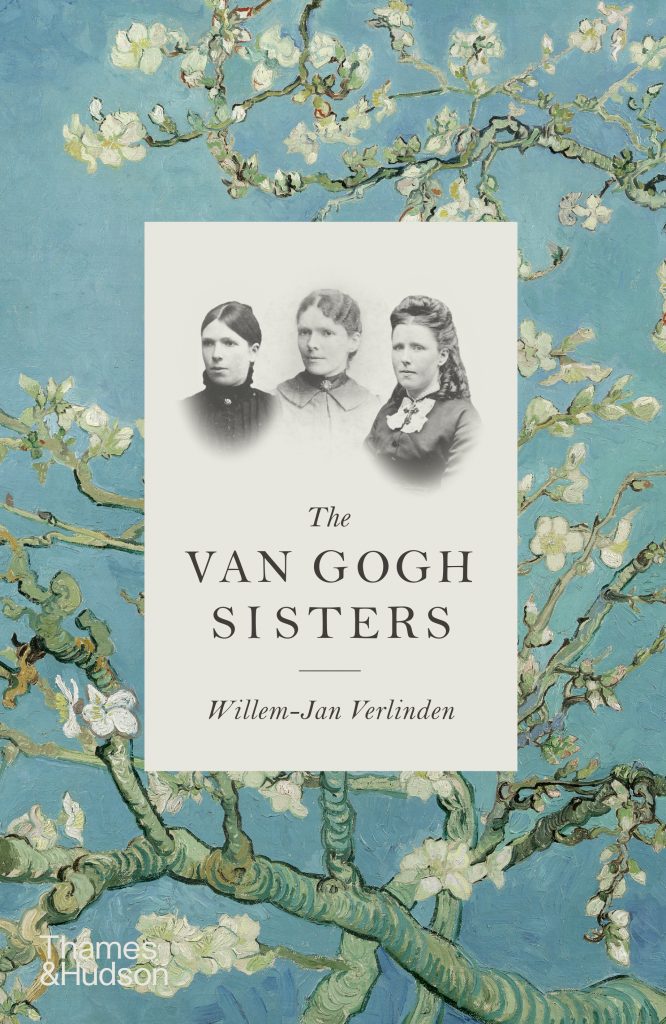

Read an excerpt from Dutch art historian Willem-Jan Verlinden's new book, 'The Van Gogh Sisters.'

Read an excerpt from Dutch art historian Willem-Jan Verlinden's new book, 'The Van Gogh Sisters.'

Willem-Jan Verlinden

Vincent van Gogh’s close and professionally fruitful relationship with his art dealer brother, Theo, is well known. But Vincent also had three sisters—Lies, Anna, and Willemien—with whom he shared dynamic, yet under-recognized correspondences throughout his life. In 1881, Vincent told Theo he had been in “constant” contact with Willemien, who also had artistic aspirations and suffered from mental health problems. Read more about Vincent and Willemien’s relationship in the excerpt that follows.

Paris, Leiden, 1888–1890

“My dear sister, Thank you very much for your letter, which I had been looking forward to. I’m reluctant to give in to my inclination to write to you often or inveigle you to do so. All this correspondence doesn’t always help to buttress those of us of a nervous disposition when we are immersed in the kind of melancholy you were referring to in your letter and which I too experience now and again.” Vincent composed this letter to Willemien over the course of four days in Arles in June 1888.

[…]

Wil and Vincent were close in spite of the distance between them as Vincent traveled from Holland to England, Belgium and eventually France, and Wil stayed largely with her mother or relatives in the Netherlands. They were frank with one another and wrote not only about art and literature, but also about love and finding a partner. Vincent often reminisced about his lost youth. When he wrote about it, his tone was melancholy. “My fates have ordained that I shall make rapid progress in growing into a little old man, you know, with wrinkles, bristly beard, a few false teeth &c. but being as I am I often work with pleasure, and I see the possibility glimmering through of making paintings in which there’s some youth and freshness, although my own youth is one of those things I’ve lost. If I didn’t have Theo it wouldn’t be possible for me to do justice to my work, but because I have him as a friend I believe that I’ll make more progress and that things will run their course.” Other passages on the same subject touch on the forces that drive his work. “As for me,” he wrote, “I keep having the most impossible and unsuitable love affairs which, as a rule, leave me battered and bruised…[but] through my love of art true love disappears.”

Courtesy of Thames and Hudson.

Vincent and Willemien formed a strong bond when they lived together at the parsonage in Nuenen. But for a time after their father’s death in 1885 and his quarrel with Anna, Vincent wanted nothing to do with Willemien. He wrote to Theo around that time: “I find them at home (I know—contrary to your opinion and contrary to their opinion) very far, very far from sincere, and since there are also other things I object to for what I believe are sound reasons, I think Pa’s death and the settlement of the estate is a point at which I will withdraw very discreetly… Do you remember how sympathetic I was to Wil when I wrote to you when Moe was ill. Well, it was over in a trice – and it’s frozen again… I can see that you’re doing your best to reconcile us. Even so, my dear fellow, I really wish her no harm and I really won’t do them any harm. Only I have no desire to try and persuade them, firstly because they don’t understand, but secondly don’t want to understand.”

However, after moving to Paris in late February 1886, Vincent found himself missing his mother and Wil, and resumed his correspondence with his youngest sister. He was proud that she and Lies were looking after the ailing Mrs. Du Quesne in Soesterberg. From the long letters he sent Wil from France we can deduce what she must have written about it to him, illuminating their shared interests. He wrote to her as an elder brother, protective and ready to advise, but his letters were also humorous and cheerful. He and Wil often exchanged ideas on literature, love, color, the sun, southern Europe and, needless to say, art. Their correspondence in this period was warm and communicative. Wil was interested in her older brother’s ideas about his work not only from a personal point of view but also because she apparently drew inspiration from his style and choice of subject matter for her own experiments with drawing. After receiving two drawings from Wil, [her friend, the feminist translator] Margaretha Meijboom wrote to her: “I am returning the Sunflower to you. I do not think it as good as the previous ones. The draughtsmanship of the Mother and Child lacks confidence. These are not ordinary people, but nor are they fantastical beings. The mother with her yellow paper flower is simply dreadful. Her saying, ‘The sun has set in my son’s garden,’ is incongruous there. The style, too, is inconsistent. One moment you are up in the air, fearless and proud, and then suddenly you go and sit on the ground. All in all, it makes me dizzy because of the many bad transitions. And, to my mind, you could certainly present the idea in nicer, more suitable packaging. I would advise you not to send it. Am I getting ‘the children’ on loan? I’d say I deserve it for my blunt grumble about ‘the Sunflower.’” Margaretha’s frank evaluation of these drawings indicates that Wil shared her artworks with her friends, and was open to criticism. Indeed, she apparently made a point of explaining how she chose her subject matter and working methods: “Now I understand that the inconsistencies in your drawing of that mother were deliberate, and the Sunflower too, but your intentions were not clear and that is why it looked wrong. At least to me, but then I do not consider myself an authority.”

Vincent van Gogh, Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers (1889). Courtesy of the Van Vogh Museum.

Margaretha was apparently fond of Vincent and saw something of herself in him. In 1888 she wrote, “Glad that Vincent’s doing so well. I should be delighted if he were to come again. I have always felt an affinity with him and his struggle with the world.” Wil forwarded some of Vincent’s letters to Margaretha, who commented on one: “Vincent’s letter is quite extraordinary. I had not realized he was so cultured, Wil! Or so deep and well-read! And how highly he thinks of Theo! I can imagine that it must have been extremely gratifying to have that glimpse into his soul. I completely disagree with his views on love. Life has forced me to accept what he calls love. Well, I can live with that, but there is also another kind, purer, loftier and nobler than he has in mind, which makes one’s whole life sunny and bright whenever it shines through the mist, as powerful and invincible as a storm, yet still not egoistic, which takes you much further as an artist, whereas his concept [of love] does not offer much, I believe. Besides that, I agree with him that an artist learns more from life than from study… Nice what Vincent says about serenity and about burning rather than suffocating. The same idea in a different form came to mind when we were sitting at the seaside. Tired as I was from all the struggle and turmoil, I nonetheless thought ‘sooner be crushed by waves than wither away on a rock.’”

Margaretha was commenting on a letter that Vincent had sent to Breda in October 1887 and Wil had forwarded to her. In it, Vincent had advocated that young women should lead relatively conventional lives. He rejected the idea of studying in order to become a writer or painter, and offered his sister advice on how to find happiness, suggesting that she should enjoy herself, live life to the full and avoid anything that might give rise to pessimism. But he appears to have been ambivalent. On the one hand, he was trying to curb Wil’s ambition, whereas Margaretha was encouraging her. At the same time, he wrote, as Margaretha acknowledged, “Whatever is inside must come out.”

Vincent and Wil were each aware of the other’s struggles with their mental health and their discussions of the topic were frank and compassionate. On 31 July 1888, Vincent wrote, “Are you in good health? I hope so. The main thing is for you to spend a lot of time outdoors. I’m often troubled by not being able to eat, more or less like you that time. But I manage to steer clear of the rocks. If you’re not strong, you have to be smart; you and I, with our constitutions, should take that to heart.” Vincent was referring to the months in 1884 when Wil was confined to bed with severe abdominal pains. He wrote to her again in late April or early May 1889—in French, which he preferred to Dutch by then—and told her that he would be admitted to the hospital in Saint-Rémy “for three months or less,” after having suffered three “attacks.” He had lost consciousness on those occasions “for no plausible reason” and had no recollection of what had happened or what he had said or done. Later, Vincent wrote that he felt unable to explain exactly what he was suffering from: the symptoms included anxiety attacks, a feeling of emptiness, fatigue and depression with no apparent cause. He adopted the formula prescribed by his literary hero Charles Dickens to banish thoughts of suicide: a daily glass of wine with some bread and cheese, and a pipe of tobacco. In October 1889, he told Wil that, according to the doctor Theo had sent to examine him, he was not insane, nor was his moodiness precipitated by alcohol. His seizures were epileptic. His mother’s sister, Clara Carbentus, had been diagnosed with the same disorder a few decades before.

Excerpted from The Van Gogh Sisters, by Willem-Jan Verlinden © 2021 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London. Text © 2021 Willem-Jan Verlinden. Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc.