Art & Exhibitions

In the Venice Biennale’s ‘Viva Arte Viva,’ Shamanism Sneaks Back Into the Picture

Primitivism makes an unexpected return in Christine Macel's therapeutic vision.

Primitivism makes an unexpected return in Christine Macel's therapeutic vision.

Ben Davis

The “return to order” is a well-worn theme, both in art history and on the contemporary art circuit. Every so often, the political energies within art get unruly or uncomfortable or exhausted enough that the “return” is announced once again. Beauty/feeling/whimsy/fantasy/tradition… it’s back, baby!

When announcing that French curator Christine Macel would organize the 2017 show, the Venice Biennale organizers were more or less explicit that they were looking for a change following Okwui Enwezor’s aggressively outspoken 2015 edition, which went so far as to include a reading of Marx’s Capital in its entirety as a centerpiece.

“In the wake of the Biennale Arte directed by Okwui Enwezor, centered on the theme of the rifts and divisions that pervade the world, and aware that we are currently living in an age of anxiety, La Biennale has selected Christine Macel as a curator committed to emphasizing the important role artists play in inventing their own universes and injecting generous vitality into the world we live in,” Biennale president Paolo Baratta said at the time.

It was a notably muddy statement of intent, seeming to charge Macel with getting away from all the controversial stuff while also addressing it, either by offering solutions or just making people forget about it. It wasn’t clear.

Entrance to the Arsenale, with “Viva Arte Viva” signage. Image: Ben Davis.

That muddiness follows us into the resulting big show in interesting ways. Overall, the 2017 Venice Biennale gives off a highly accomplished, though slightly underthought, vibe. That includes the title, “Viva Arte Viva,” which is almost charmingly hokey: At a time when art might feel overrun by events, it literally sticks “art” at the center of “life.”

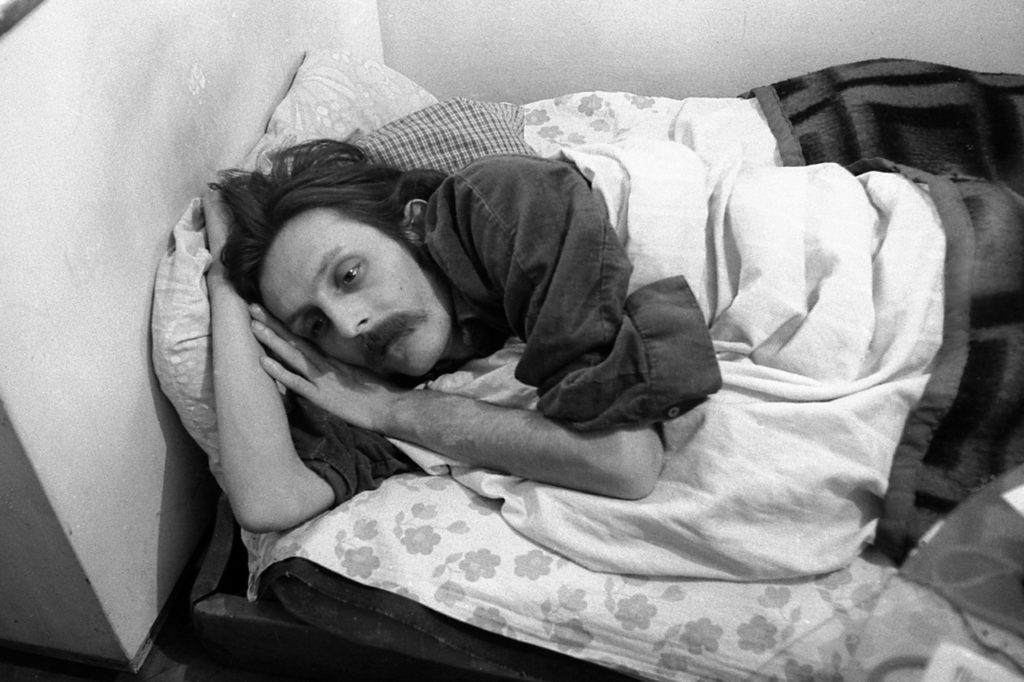

Mladen Stilinovic Artist at work (1977). Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

At the Central Pavilion, the first section of “Viva Arte Viva” greets you with the “Artist at Work” series of Belgrade-born Mladen Stilinović (1947-2016). This is probably the most willfully low-key shot possible to fire at the start of a show, photographs showing the artist… just sleeping.

As an opener, it seems more or less a direct reply to Enwezor’s theatrically “woke” Biennial. But it’s a canny choice for this purpose: Stilinović’s Eastern European conceptualism was, in its original form, a sort of a riposte to the socialist rhetoric of its day (the 1970s), and so can be thought of as political in its own non-comformist, unconventional way.

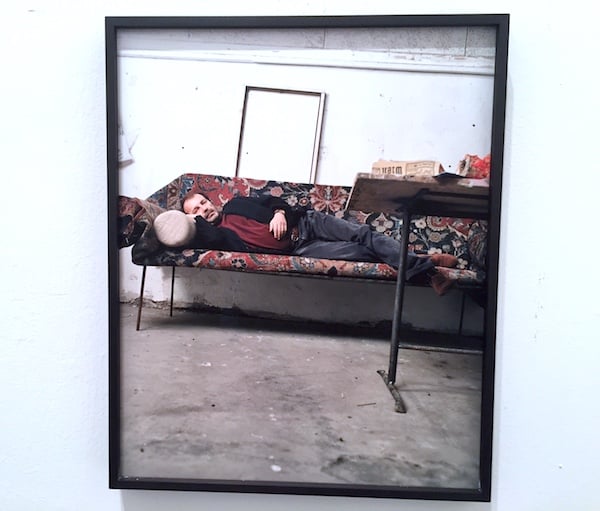

Photo of Franz West asleep. Image: Ben Davis.

Take a further turn into “Viva Arte Viva,” and there’s a photograph of Stilinović’s more famous Austrian contemporary, Franz West (1947-2012), also sleeping. Good art doesn’t try too hard, it seems to say. Good art is refreshing, like a nap. And then there’s artist duo Yelena Vorobyeva and Viktor Vorobyev (both b. 1957), just around the corner, with their life-sized tableau The Artist Is Asleep (1996), just to make it clear.

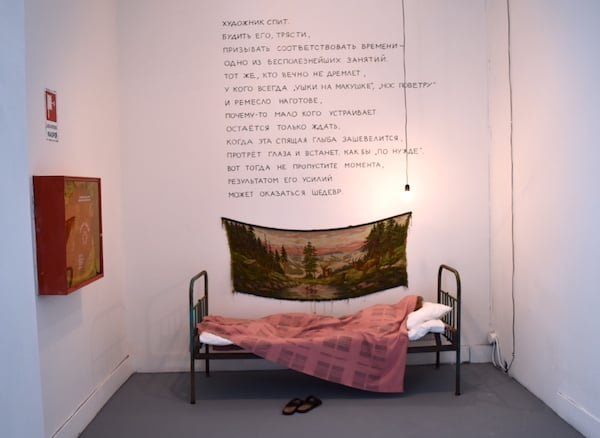

Yelena Vorobyeva and Viktor Vorobyev, The Artist Is Asleep (1996). Image: Ben Davis.

Macel doesn’t just want you to consider art’s soporific powers, of course; she is making a claim for its power to dream.

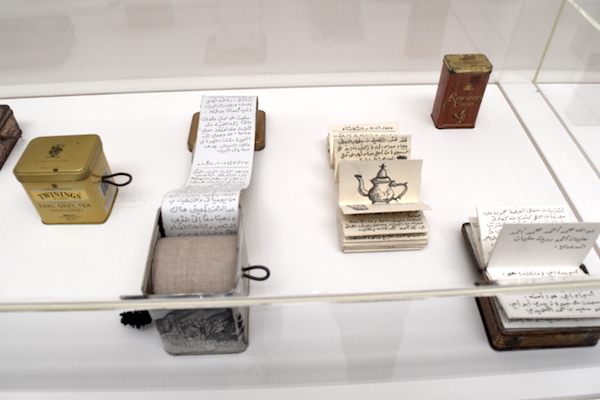

And, at its many high points, “Viva Arte Viva” shows art dreaming with a lonely and articulate beauty. For instance, see the witty little hand-drawn Arabic scrolls, nested into household tins, of the Emirati conceptual art pioneer Abdullah Al Saadi (b. 1967).

Abdullah Al Saadi, Al Saadi’s Diaries (2016). Image: Ben Davis.

Or the wall-filling video mosaic of multiple, coordinated sunsets by American video artist Charles Atlas (b. 1949)—nature at its most stock sublime paired with audio of a raw sermon about the corrupt state of politics from drag star Lady Bunny.

, and <em>Chai</em>. Image: Ben Davis.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2017/05/charles-atlas.jpg)

Charles Atlas’s The Tyranny of Consciousness [left] (2017), and Chai. Image: Ben Davis.

Yet any show of the Venice Biennale’s size and resources can marshal excellent works. The test is whether its vision holds it all together.

You might be able to tell what is on the mind of “Viva Arte Viva” by what is not in it. Contemporary politics are muted, of course; hardly a whisper of current events sneaks in. And yet, despite its not-so-implicit brief to restore the comforting side of art, “Viva Arte Viva” is notably not a “back-to-painting” biennale. There is painting, some of it interesting, but it’s a dispersed substance within the larger brew.

Paintings by Hao Liang. Image: Ben Davis.

“Viva Arte Viva” is also light on technology. Racking my brains for the most in-your-face, high-tech-seeming thing here, what comes to mind is an interactive DVD, Mon Encyclopedia Clartes, that the late French artist Raymond Hains (1926-2005) put together with Macel for his 2001 retrospective at the Pompidou. It is presented for your perusal in the gallery devoted to his raucous body of work, via a deliberately funky old iMac—a sign of antique cool.

The show’s sensibility is very much trying to place you outside of the cycle of the present.

Raymond Hains’s DVD project Mon Encyclopedia Clartes, as presented in “Viva Arte Viva.” Image: Ben Davis.

What Macel’s show is heavy on is craftsiness. For instance, there’s Chinese artist Lee Mingwei’s The Mending Project (2009-2007), which invites visitors to contribute clothing they want mended to the installation.

A tailor at work for Lee Mingwei’s The Mending Project (2009-2017) at the Venice Biennale. Image: Ben Davis.

Nearby is Filipino artist David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time, originally from 1968, recreated as an embroidery project inviting people to stitch whatever scraps that represent their experience onto a shared draped swatch of fabric, forming a collective portrait of the moment. That’s two setpieces involving participatory needlework!

Visitors interact with David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time (1968/2017). Image: Ben Davis.

A relative lack of paint-on-canvas work is made up for by a surplus of textile works, draped painting-like on the walls, and intimately crafted things, presented on shelves or on tables. Even some of the more impressive beats of the show—say, Leonor Antunes’s delicate, shimmering hangings and dangling lamps made in the Murano glass workshops, and Sheila Hicks’s climactic wall of multicolored pompoms—are examples of craft exaggerated to the level of spectacle.

Leonor Antunes’s …then we raised the terrain so that I could see out (2017). Image: Ben Davis.

Craft, with its associations with comforting tradition, connects to what I take to be the larger presiding theme of the show: the power of personal ritual.

This Biennale is full of artists who stage self-invented rites of psychic nourishment (Lee Mingwei’s dream-like ceremony in the Grand Pavilion; Anna Halprin’s choreography meant to aid in community healing), or make their art available as a prop for low-fi self-expression (Rasheed Araeen’s colorful towers of cubes, which you are meant to handle; Dawn Kasper’s transformation of one gallery into a cluttered workshop in which to improvise work), or just present an art of rough DIY edges as if to say, “Hey, take pleasure in the small things.” (Maria Lai’s books bound in bread; Michel Blazy’s display of sports shoes made into planters.)

Michel Blazy’s Collection de Chaussures (2016-17), featuring plants growing out of sports shoes. Image: Ben Davis.

In that sense—coming full circle to the political “age of anxiety”—Macel’s “Viva Arte Viva” reads as an essay on contemporary art as coping mechanism, turning towards small-scale epiphany as the world outside becomes more menacing.

This compensatory narrative brings us to an issue worth addressing: Compared to the 2015 Enwezor show’s unusual, and exciting, emphasis on artists from Africa, Macel’s roster definitely reorients its conversation around artists living or working in the traditional European center (though it has a nice emphasis on Eastern Europe). At the same time, the show puts a curious accent on works that speak with an almost anthropological voice about non-Western cultures.

Just as Stilinović’s “Artist At Work” series introduces the themes of the Central Pavilion, in the Arsenale section of the show Chile-born artist Juan Downey (1940-1993) sets the tone with his video sculpture, The Circle of Fires Vive (1979): stellae of paired video monitors organized in a low-slung circle, playing identical footage he took while living among an indigenous tribe in Latin America during a sojourn in the ’70s.

Juan Downey, The Circle of Fires Vive (1979). Image: Ben Davis.

There’s more work with anthropological themes throughout—but let’s just skip to where the theme reaches its spectacular peak: Brazilian star Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place) (2017), a gallery-filling pavilion made of soft, colorful mesh. The work introduces the section Macel has actually dubbed the “Pavilion of Shamans,” proposing that we live in a time where “the need for care and spirituality is greater than ever,” and looking to artists who connect us to the wisdom of Sufism, Buddhism, and, here, indigenous peoples.

Ernesto Neto, Um Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place) (2017). Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia; photograph: Andrea Avezzù.

Just as Downey’s circle of video monitors was meant to evoke a “shabono,” or gathering place for the Yanomami people, the text beside Neto’s work explains that it was inspired by a “Cupixawa, a place of sociality, political meetings, and spiritual ceremonies for the Huni Kuin Indians.” It is meant to evoke the site of a sacred ayahuasca ceremony—though it mainly ends up as a funky chill-out zone for art tourists.

Visitors lounge in Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place) (2017). Image: Ben Davis.

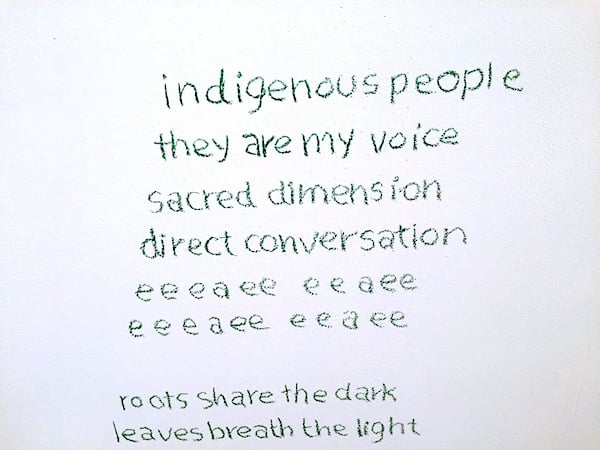

Downey, for one, was very aware of the dangers of anthropological-style imagery in enforcing stereotypes, and tried to cut against them (though critics have argued that, in the end, he failed to escape a “primitivist” frame). Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar is accompanied by a sincere written plea to pay attention to the plight of indigenous Brazilians, and a group of tribal members have willingly accompanied him to the Biennale to perform. Someone, however, might have edited the hand-written texts studding the walls around his pavilion to make them sound a little bit less like ‘noble savage’ boilerplate.

Piece of a poem, written on the wall, to accompany Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar. Image: Ben Davis.

Whatever the case for individual artists, taken with the overall percolating ‘healing ritual’ aspects of Macel’s exhibition, this shamanistic sub-theme returns us to what seems a half-thought-through primitivism: offering redemption for a corrupt Western world in the wise Other.

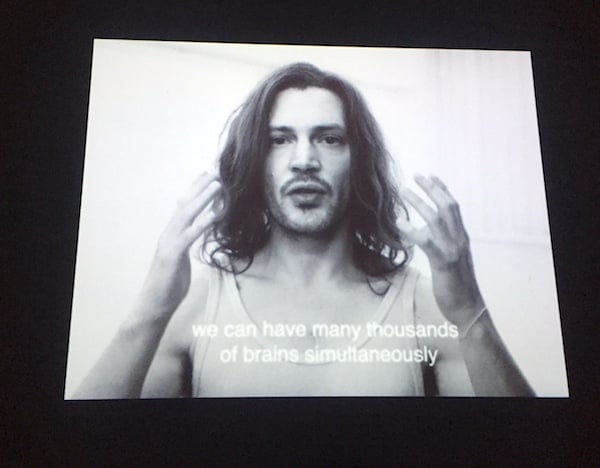

A final, funny thing about this show: My favorite discovery, a 20-minute film by the Canadian artist Jeremy Shaw (b. 1977), could almost serve as an internal critique of “Viva Arte Viva” and its disposition.

Called Liminals (2017), and made specifically for the Biennale, it is a science-fiction pseudo-documentary. A narrator explains the grainy footage: In future times, as the certainty of human extinction comes to weigh more and more on the species, a group called the “Liminals” form a sort of cult, trying to restimulate the parts of their brain that activate the lost sense of religious belief.

Image of Jeremy Shaw’s Liminals (2017) in the Venice Biennale. Image: Ben Davis.

They speak their own nonsense language (subtitled in the film). You watch them thrash around in rituals of ecstatic awkwardness—attempting, we are told, to return to a time before the nightmares of the modern world via the ecstatic rituals of an earlier time.

“Our extinction is a quantifiable certainty,” the narrator of Liminals intones at one point. “Thus, the quest of the Liminals, and of periphery Altraist cultures in general, to incite evolutionary advancement in an effort to save humanity is more consistent with the types of reactionary developmental syndromes found in societies during End Times than a plausible attempt for redemption. Nonetheless, their diligence and commitment to such fantastical ideas is rather fascinating.”

The neat thing about Macel’s Biennale in relation to Enwezor’s is that it seems to suggest that certain emphases in contemporary art—on magical thinking, on personal myth, on local epiphany—represent exactly a “reactionary developmental syndrome.” In the face of an unspoken and intractably apocalyptic sense of the world, they look to rekindle forms of imaginary redemption, taking on a slightly unworldly feeling as a result. And it’s true: The commitment to such fantastical ideas is rather fascinating.

“The Venice Biennale 2017: Viva Arte Viva” is on view in Venice through November 26, 2017.