Art World

Vicky Colombet Finds a Sense of ‘Home’ in Her Aerial-Inspired Paintings

The French-American artist's solo exhibition "Flying Back Home" is now on view at Fernberger Gallery in Los Angeles.

The French-American artist's solo exhibition "Flying Back Home" is now on view at Fernberger Gallery in Los Angeles.

Katie White

French-American artist Vicky Colombet (b. 1953) has made the flight between New York and Paris many times. But the sight of the mammoth waves of the Atlantic Ocean from tens of thousands of feet above, abstracted into inky scribbles and scrawls in shades of blue has never failed to amaze her.

The vastness of these elemental forces— the ocean, the cosmos, the earth itself—is what inspires much of the artist’s enigmatic abstractions. Earlier this month, the artist opened “Flying Home” her West Coast solo debut at Fernberger Gallery in Los Angeles. Colombet presents some of her most nuanced works to date, monumental pieces made of pigment, oil, and alkyd on linen in a limited palette of blues and blacks.

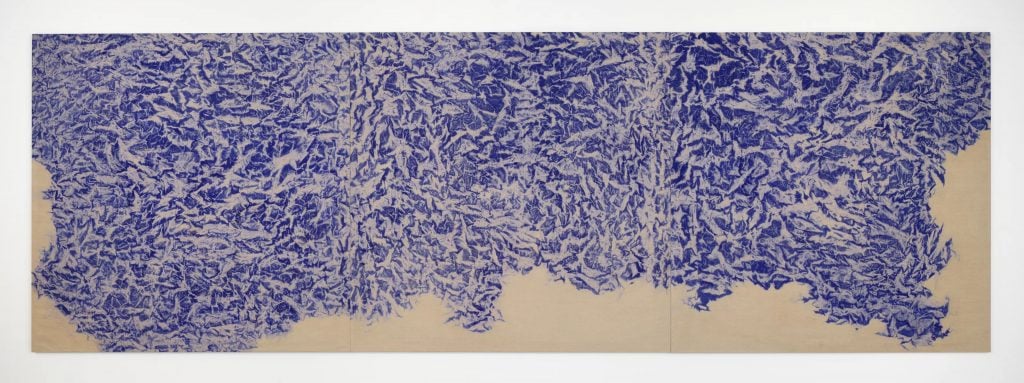

These works are a continuation of the “Pils et Paysage” (“Folds and Landscape”) series she began in 2015. Here Colombet stretches her highly controlled works to new limits. Anchoring the show is the monumental triptych Flying Home #1569, which sprawls some 20 feet wide across three canvases and stands at over six-and-a-half feet tall.

Vicky Colombet, Flying Back Home #1569 (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Fernberger Gallery.

Her process borders on the scientific with Colombet grinding raw pigment—blue green, cobalt, cobalt blue sapporo, iron oxide black, ivory black, and ultramarine light titanium white—into solvents, toying with chemical responses to create the unique effects of color on linen that define her works. Her rhythmic painted gestures are elusive and mysterious (she paints with the canvas flat) and her abstracted forms interact with negative space like Rorschach tests. These works can seem aerial in perspective, like mountain ranges seen from on high, or the ocean, or cracked desert earth. But other times, the gestures call to mind herds of animals, flocks of birds, and even cave paintings.

Today, the artist works between a studio in New York City and another in the countryside of Hudson Valley. We recently spoke with the artist about the metaphysical questions that drive her and why her biggest works aren’t yet big enough.

Inside Vicky Colombet’s studio, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Fernberger.

Your show is titled “Flying Back Home.” You’ve lived a very global life. What does that title mean to you? What does home mean to you? How does that show up in these artworks?

I became an American in 2013. France is where I was born, where I come from, and America is where I am, where I live. The past and the present. But I can say that I am flying back home in both directions. It is always inspiring to look at the sea from a plane and to observe the French and American landscape from above before landing. Many of my paintings look as if they were aerial views.

I have traveled quite a bit. And I learned that landing and arriving Home in the Buddhist practice with the Zen monk Thich Nhat Hanh, is to be strong, stable, and at peace. Being Home is wherever I am.

Vicky Colombet in her studio, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Fernberger.

How does your relationship with nature, with your surroundings upstate, materialize in your artworks? Has your relationship to nature changed over the course of your life?

In my work, I’m often not referring to a particular landscape per se, but rather trying to create a visual catalyst that prompts our thinking of places and how we imagine them. For years, I worked on a series of paintings about Antarctica, and I have never been there. The beauty of the ice disappearing before our eyes, endangering the wildlife as well as the entire planet. Nature, time, water, light, and contemplation are conveyed through abstraction. Not to copy or reproduce a landscape but to channel the soothing and obvious idea of painting like the river and letting the elements—wind, water, and Earth—take place there through fluidity, brush, and pigments. These are intuitive paintings. My relationship with nature has evolved across all these years. I need nature more than ever—the healing gift of nature. For Schopenhauer, “Pleasure from knowledge of observer’s nothingness and oneness with Nature” was the ultimate definition of the sublime.

Inside Vicky Colombet’s studio, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Fernberger.

Who are some of the artists who you’ve learned the most from or found the most inspiring?

Fra Angelico, Piero Della Francesca, Giotto, Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, Ellsworth Kelly. The beauty, the quest for light and the beyond, and the extraordinary complexity of simplicity.

Tell us about your studios.

In the early 90’s I had a large studio in Barcelona with no heat, and did very large paintings there. And then a large studio in the south of France with no heat and the rain leaking in where I did large and small paintings.

Now I have a very small studio in the city and a larger one in the country. They are complementary. I would define the small studio as a thinking place, where I can slow down and draw, and paint small, intimate paintings. I feel more contained and safer, the walls are close. My imagination pushes through the walls.

In my larger studio, there is action. I feel the speed, the space that invites movement and allows larger paintings and bigger projects. But I am still pushing through the walls. Never big enough.

Inside Vicky Colombet’s studio, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Fernberger.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work?

I like to listen to music and I also like to listen to the birds and frogs outside my studio upstate and the silence. Sometimes I look at the notes I took while reading. And words are often an inspiration.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

I just work and work until I find a path. Or even a glimpse of a path.

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most, and why? Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

I work with pigments which are for me the quintessence of painting. They’re also a metaphor for the particles of the universe. Every pigment has its own property and chemical response when mixed with fluid mediums. The same way you would observe the difference between a granite or a limestone landscape. Every pigment reveals a different landscape formation. If you pay attention to it, it opens a world of visual possibilities. I also work with goat and squirrel brushes which are very smooth and don’t leave brushstrokes, which reinforces the mystery. This split-second of a moment where you stop and look to try to decipher. Is it a painting? And because you are not sure, you begin to imagine.

Inside Vicky Colombet’s studio, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Fernberger.