People

Virginia Dwan, Pioneering Dealer Who Bankrolled Some of Land Art’s Most Daring Masterpieces, Has Died at 90

Among the projects she helped fund were Robert Smithson's "Spiral Jetty" and Michael Heizer's "City."

Among the projects she helped fund were Robert Smithson's "Spiral Jetty" and Michael Heizer's "City."

Sarah Cascone

Pioneering art dealer Virginia Dwan, who was instrumental in establishing the Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Land Art movements, has died at the age of 90.

It was Dwan who helped fund such landmark works as Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969), two massive trenches dug in Nevada’s Moapa Valley, and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), a monumental coil of basalt rocks off the shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. She also gave Heizer a loan to purchase the land on which to build his magnum opus, City, which finally opened this month, and commissioned the first version of Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field.

Supporting such complex undertakings required visionary thinking. But it was the sheer scale of these projects that made Dwan want to help realize the works.

“A canvas has boundaries; it has limit to it. And for earthwork, it was the very openness and feeling that there were no boundaries that made it so exciting,” she told Interview magazine in 2015. “For me it wasn’t a leap of faith. I was thrilled.”

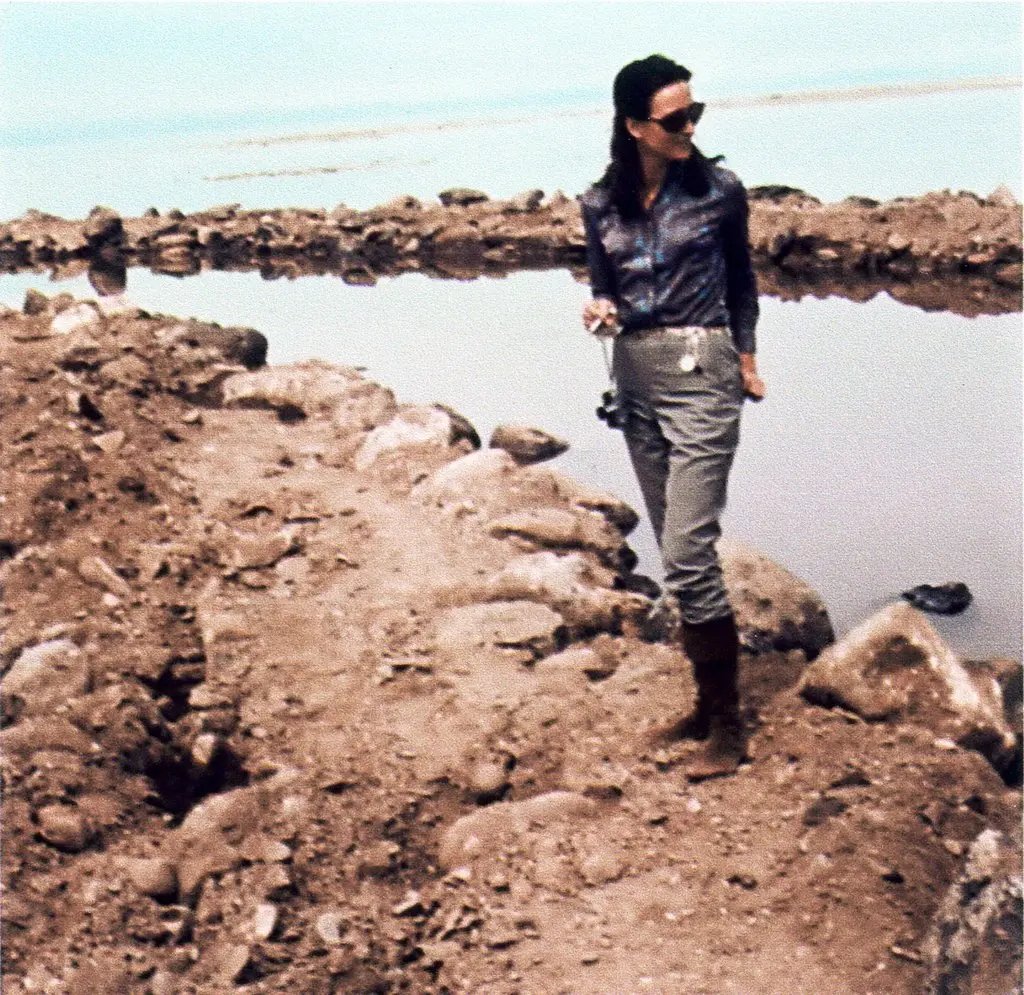

Virginia Dwan at Spiral Jetty (1970), Robert Smithson’s landmark Land Art work. Photo: Nancy Holt, courtesy of the Holt/Smithson Foundation.

Although Dwan, whose death was first reported by ARTnews, didn’t complete her art studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, she opened her first gallery in the city in 1959.

“I had wanted to have a gallery for some time, though I didn’t know anything about it, really,” Dwan told Artforum in 2014. “I just went ahead and did it anyway—the Innocents Abroad sort of thing.”

Born in Minneapolis in 1931, Dwan was one of 17 heirs to the 3M conglomerate, a health care and consumer goods company perhaps best known for its adhesives. It was that inheritance that helped build the foundations for her business, and allowed Dwan to act as a patron to so many artists. (The New York Times once dubbed her “a jet age Medici.”)

Virginia Dwan in her New York gallery (1969). Photo: courtesy of the Dwan Gallery records, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C.

“I have to acknowledge the fact that I had a private income myself which made it possible for me to take a more idealistic stand, or devote myself more to the artist than perhaps a lot of other dealers would do,” Dwan said in an interview with the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. “I knew I was going to be able to keep the doors open.”

Dwan went on to exhibit the likes of Ad Reinhardt, Edward Kienholz, Joan Mitchell, Franz Kline, and Philip Guston. For Mark di Suvero, she cut a hole in the gallery ceiling to accommodate a work that was taller than the space. In 1961, she gave French artist Yves Klein his first U.S. show. Robert Rauschenberg’s first West Coast outing came the following year.

(Despite her status as a female dealer, Dwan, perhaps a product of her time, operated something of a boy’s club.)

Also in 1962—shortly after Andy Warhol famously had his first show at Ferus Gallery, also in Los Angeles—Dwan staged one of the nation’s first Pop Art exhibitions. Titled “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” it featured work by artists including Marisol, John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, and Tom Wesselmann.

“My Country ’tis of Thee” at Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1962. Photo: courtesy of the Dwan Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C.

In 1965, Dwan opened a second location in New York, becoming the nation’s first bicoastal gallery.

“Art history has validated her taste,” James Meyer, then chief curator and deputy director at the Dia Art Foundation, which owns Spiral Jetty, told Vogue in 2016, on the occasion of an exhibition dedicated to Dwan he curated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The show featured selections from the Dwan Gallery Archives at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, as well as 100 of the 250 works that she had promised to the museum, by artists such as Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Agnes Martin, Jean Tinguely, and Sol LeWitt.

Though Dwan’s legacy is undeniable, her career as a dealer came to an early end, due in part to her refusal to compromise by showing more commercially appealing work. She shuttered her L.A. location in 1967, before closing down entirely in 1971 to devote herself to filmmaking and photography.

Later projects included the Dwan Light Sanctuary, a collaboration with solar spectrum artist Charles Ross and architect Laban Wingert, which opened in 1996 at United World College in Montezuma, New Mexico,