What led to the demise of the Roman Republic? Experts now believe that the eruption of a remote Alaskan volcano may be partly to blame.

The Okmok volcano erupted early in the year 43 BC, spewing clouds of ash into the atmosphere and blocking the sun’s rays, causing two of the coldest years in the past two and a half millennia. The event triggered a famine that exacerbated existing political tensions in Rome and led to the rise of the Roman Empire, according to a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“I find the timing of such a massive eruption in Alaska with respect to such important historical and political changes in the Mediterranean very intriguing,” Joseph McConnell, a climate scientist at the Desert Research Institute in Reno and the study’s lead author, told Artnet News in an email. “Was it all a coincidence? Maybe, but logic would suggest that the very unusual weather caused by the Okmok eruption must have played a significant role.”

There is some debate as to when the Roman Republic met its end, but the assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BC, was clearly a watershed moment in its history. What no one realized then was that 6,000 miles away, on Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, even bigger trouble was brewing as Okmok rumbled to life.

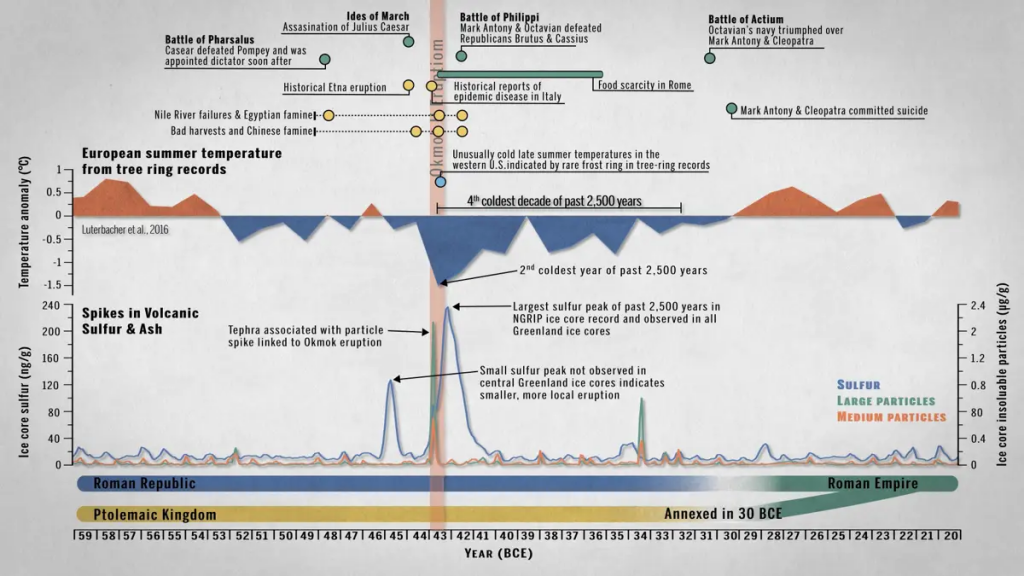

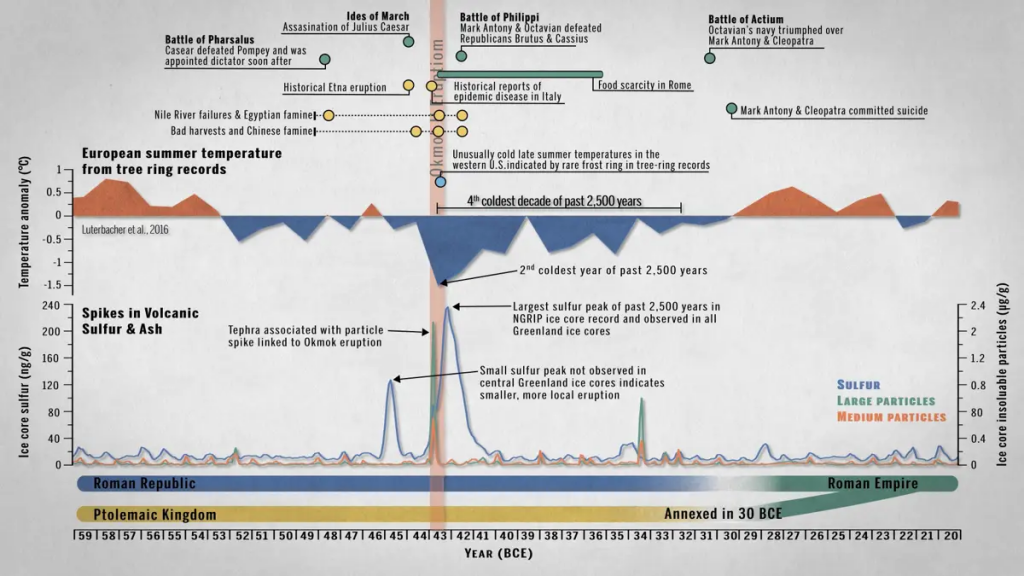

A timeline of events in the Roman Republic and Egyptian Ptolemaic Kingdom around the time of the Okmok eruption. Image courtesy of the Desert Research Institute.

During the civil war that followed Caesar’s death, written accounts remarked on the unusual weather—the sun didn’t shine, and the weather was unusually cold and wet, leading to famine. Historians have previously speculated that a volcano was to blame, and now geoscientists, historians, and archaeologists have been able to physically investigate that theory.

The new study analyzed six Arctic ice cores, drilled vertically from glaciers in the 1990s. Each core has layers, much like tree rings, which allow scientists to drill back in time, examining the ice year by year, based on the varying elements present in the frozen sample. At the Desert Research Institute’s Ice Core Laboratory, the cores were melted down and the water analyzed by sensitive instruments.

Detailed records of past explosive volcanic eruptions are archived in the Greenland ice sheet and accessed through deep-drilling operations. Photo by Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, paleoclimatology professor and researcher at the Centre for Ice and Climate at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

“Because of atmospheric circulation,” McConnell explained, “we can and do develop very detailed records, including of past explosive volcanism and industrial pollution, even from ice cores located in the Arctic far from the sources.”

McConnell and his team soon realized that the ice from 43 BC had an unusual amount of tephra, a material produced in eruptions, which was evidence of one of the biggest volcanic events of the last 2,500 years. But first, they had to figure out where that volcanic ash originated.

The tephra from each volcano is unique, representative of the specific rocks and magma. That means scientific testing can identify the origins of each individual sample. The 35 samples taken from the ice cores didn’t match the rock chemistry of nearby Mount Etna, Apoyeque in Nicaragua, or Shiveluch in Russia. Instead, it was the distant Okmok. Testing samples from the ice and from Okmok on the same instrument confirmed the match.

“There are some events that are tricky. With Okmok, there’s nothing else that looks like it,” Gill Plunkett, a paleoecologist at Queen’s University Belfast, who conducted the test, told the New York Times.

Okmok Caldera, Alaska. Photo by J. Reeder. Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys.

The study used climate models to see how Okmok’s eruption would have affected the Mediterranean, and found that temperatures could have dropped up to 13.3 degrees Fahrenheit, with precipitation increasing up to 400 percent.

The Roman Republic was already on the brink of collapse, and it may have been Okmok that was the final straw. “My understanding is that food scarcity and associated civil unrest was pretty common during the Roman Republic, so it wouldn’t have taken much of a disruption in food production to push the Republic from scarcity to shortage and famine, with disease and riots following close on the heels of famine,” said McConnell.

The effects of Okmok also rippled out to ancient Egypt, its dark cloud of volcanic aerosols possibly causing a drought in Africa. The resulting Egyptian famine likely made it easier for Octavian to defeat and annex the fallen Ptolemaic Kingdom as part of the nascent Roman Empire in 30 BC.