Archaeology & History

Could the Mysterious Voynich Manuscript Actually Be About Sex?

A new study posits that the ancient work encodes "women's secrets."

It’s been an unusually long time since anyone claimed they have cracked the century-long case of the Voynich Manuscript’s cipher. In a new article for the Social History of Medicine, however, Macquarie University research fellow Keagan Brewer and his co-author Michelle L. Lewis seek to corroborate previous suspicions that the enigmatic illustrated text served as a medieval guide to the female reproductive system—based on its imagery and context, as opposed to its text.

The 240-page document in question takes its name from Wilfrid Voynich, the Polish book dealer who purchased the manuscript in 1912. It’s written in a code language, which wouldn’t be so hard to decipher if only experts knew exactly what language it translates to. Researchers from the University of Alberta incorrectly guessed Hebrew in 2018, and another from the University of Bristol insisted in 2019 it was written in defunct “Proto-Romance,” a claim which was debunked months later.

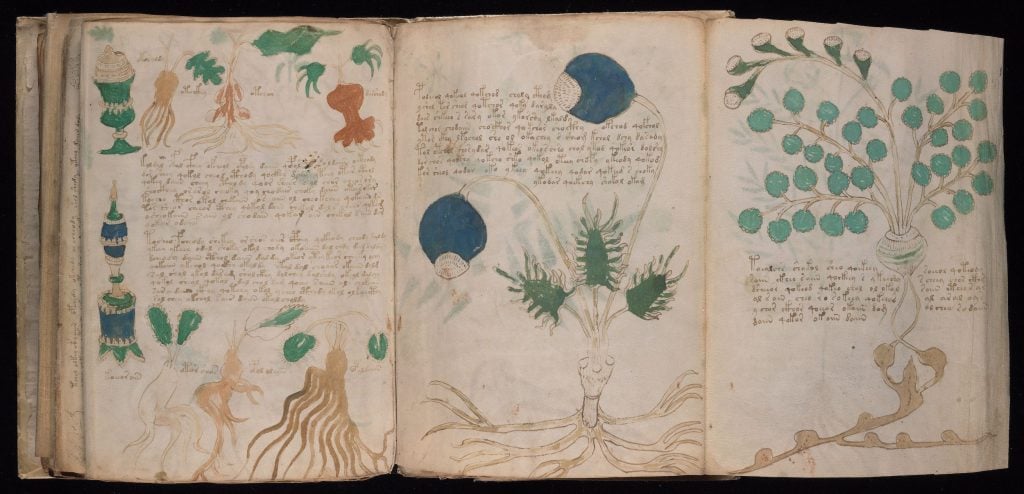

Voynich Manuscript (15th Century). Image via Yale University Library.

Carbon-dating indicates the manuscript was almost certainly written on the skins of animals that died between 1404 and 1438, as Brewer notes in an article published alongside his paper. Beyond that, experts can’t even trace the manuscript’s provenance. Its earliest known owner, a friend of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, didn’t acquire it until at least 1552. Brewer notes that certain symbols like zodiac signs and the silhouette of a unique castle wall called a swallowtail merlon “indicate the manuscript was made in the southern Germanic or northern Italian cultural areas.”

The manuscript is rife with drawings of naked women, some brandishing objects towards their crotches, which Brewer believes belies a gynecology guide. “I cannot fathom why it would be about anything else given that there are plants (which means it’s a medical manuscript) and women pointing objects towards their vaginas,” Brewer told the Daily Mail. “Many commentators on the manuscript ignore the latter fact, but they’re right there for everyone to see.”

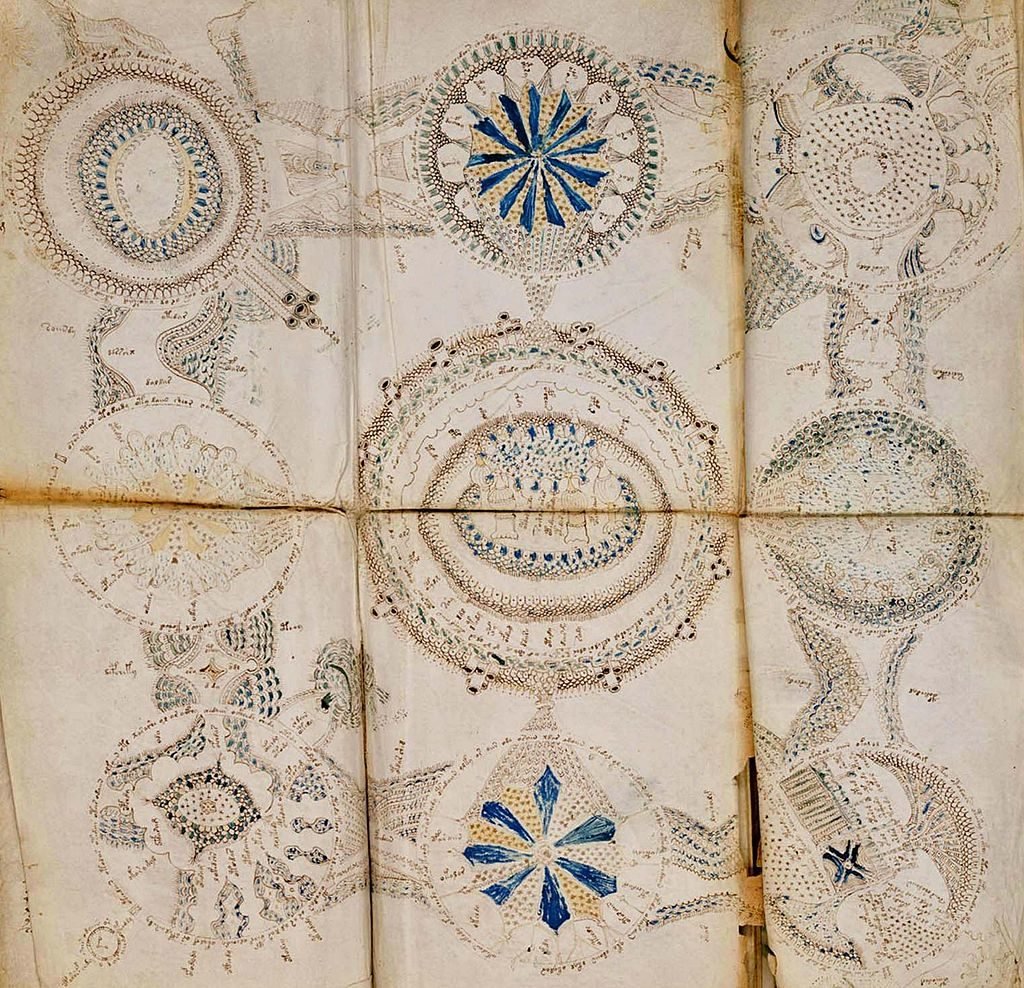

The Rosettes of the Voynich Manuscript. Photo by: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images.

First, he and Lewis studied Bavarian physician Johannes Hartlieb, who is often mentioned alongside the Voynich Manuscript because he lived in a time and place consistent with its creation and worked in the same field that the manuscript purportedly dabbles in. Hartlieb worried what women would do if they knew how to control their own bodies, so he suggested writing such medical texts in “secret letters,” or code. “As a man who valued heterosexual marriage and women’s ‘modesty,’” Brewer noted, “he was perfectly conventional for his milieu.”

That insight substantiates the inference that this text is about female anatomy and contraception. Brewer and Lewis’s visual analysis of the Rosettes—the manuscript’s most elaborate, nine-part illustration—take their claim even further.

“In late-medieval times the uterus was believed to have seven chambers, and the vagina two openings,” Brewer explained—the Rosette’s nine clear components, they think, illustrate “coitus and conception,” per the study. Five flutes shooting off the top-left circle might reference Persian physician Abu Bakr Al-Rāzī’s late medieval claim that virgins had five such veins in their vaginas. The duo also spotted references to Aristotle and German slang.

“What we hope to have demonstrated in this paper,” the authors conclude in their study, “is that amid the abundance of gynecological and sexological writing drawn up in late-medieval Europe, there were large numbers of medical writers and readers who considered ‘women’s secrets,’ or diverse aspects thereof, worthy of obscuration, sometimes in addition to other subjects such as alchemy, magic, and demons.”