Art World

Want to Commit Art Fraud? An Expert Shares 5 Strategies

The art world has become inundated with tales of fakes, frauds, and unscrupulous behavior. Here is how cons are orchestrated.

Over the last few years, the art world has become inundated with tales of fakes, frauds, and unscrupulous behavior. Starting with the Knoedler scandal, and continuing with the Orlando Museum of Art debacle, a pattern of deceit has emerged. Since the art market is unregulated, it continues to attract individuals who don’t play by the rules—because, basically, there are none. Vigilance and common sense are the keys to staying out of trouble.

The remarkable thing about art fraud is that it can literally happen to anyone. As an art authenticator, I spend my days examining random works by Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Andy Warhol, and I continue to be amazed by the forged images and fabricated provenances that I see. Over time, I’ve witnessed reoccurring scams, allowing me to compile a list of ways to commit art fraud—if you really want to. Obviously, getting away with it is easier said than done. But the following five examples bear watching, lest you get taken in by the deceptions that lie below the surface.

The Orlando Museum of Art, which presented a 2022 show of allegedly fake Basquiats. Photo courtesy Ebyabe/Wikimedia

1. If at First You Can’t Sell a Fake, Try, Try Again

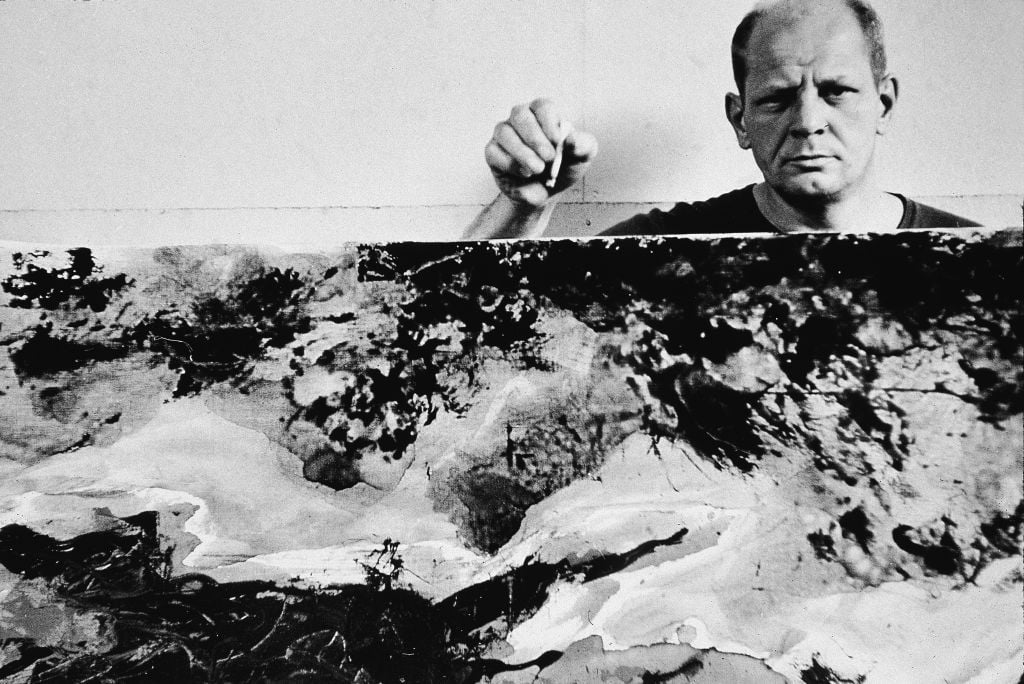

Of the seven artists I authenticate, Jackson Pollock is the most complicated. One of the reasons why is because his forgeries often come from highly improbable sources that are impossible to trace. Just during the last two years alone, I’ve learned of an alleged major “drip” painting that was discovered in Bulgaria (of all places) and another that supposedly belonged to Fidel Castro (of all people). Needless to say, neither one of these paintings turned out to be authentic.

What’s really troubling is the surprising number of “Pollock” canvases which I’ve examined, and deemed inauthentic, that then repeatedly pop up on the market like a game of Whac-A-Mole. Usually, there’s a six-month lag until the same picture shows up again. When it does reemerge, it often winds up on eBay. The seller offers platitudes about its glorious history, its extraordinary investment potential, and their rigorous vetting of the piece. Unfortunately, they conveniently leave out the “minor detail” that it was previously rejected as a fake.

An act of fraud is only committed when you sell a counterfeit painting. Up until then, you can do whatever you want with a fake picture. But if you know it’s fake beforehand, and money changes hands, then you’ve crossed over into felonious territory. The owners of these bogus Jackson Pollocks all know the truth about what they’re selling, which means they’re 100 percent liable. Proving their chicanery is the tough part. Far better to avoid getting entangled in these recycled purchases.

Jackson Pollock in his studio in East Hampton, New York, in 1953. Photo by Tony Vaccaro/Getty Images

2. Sell a Painting Allegedly Found in a Storage Locker

Dealing with a “made-up” provenance is an occupational hazard for an art authenticator. Some of the backstories that accompany fake Jean-Michel Basquiats are outrageous. I often hear about paintings and drawings that were part of a trade between the original owner and Jean-Michel for drugs. Inevitably, no one can produce the name of the drug dealer. Or I’m told that the pusher died years ago. This makes it impossible to verify the story—which is exactly what the owner wants. It’s probably true that early in Basquiat’s career he occasionally swapped his art for narcotics. But good luck proving that a particular work can be traced to a specific individual.

A more common strategy for a con artist is to claim that a painting was found in an abandoned storage locker. Everyone has heard of storage lockers whose contents were sold for non-payment. There are professional pickers who cobble together a living buying and selling recovered items from these containers. On rare occasion they score a valuable find; perhaps a piece of antique furniture or a motorcycle. However, I’ve never heard of a painting by a major artist turning up this way. It simply doesn’t work like that. Anyone who collects art is aware of how valuable Basquiat’s work has become. If you were fortunate enough to own one of his canvases, you would never keep it in a storage unit.

In London in 1950, Artists David Williams and Henley G Blake discuss the restoration of a ceiling canvas painted by Rubens. Photo by George Konig/Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

3. Sell an Overly Restored Work as an Original

Everyone is familiar with the notorious Salvator Mundi painting. To this day, no one has been able to figure out whether it was painted by Leonardo da Vinci, by his assistants (with an assist from the master), or by a completely different artist. The point is that Christie’s sold it as a Leonardo—and obviously the buyer believed this attribution. But what happens if, at a later date, someone uncovers irrefutable evidence that it’s not a Leonardo? Was fraud then committed? The answer is “no,” as long as Christie’s was fully convinced that it was real (and could provide strong evidence to back up its opinion).

This leads to another question: At what point does a work of art cross over from being executed by a specific artist, to being altered so heavily that it’s no longer his work? For example, I knew of a Joseph Cornell box where the wooden shell was fabricated by Cornell, a few of the interior objects were selected by him, and the verso of the box bore Cornell’s signature. Yet, this was clearly an unfinished assemblage. From what I understood, the piece was later restored by someone knowledgeable in Cornell’s work. But the conservator clearly got carried away; the box now contained an overabundance of ephemeral objects and came off as too slick. If you’re going to commit art fraud by completing an unfinished work, make sure you exercise restraint.

The recent story about A.I. being used to complete one of Keith Haring’s last paintings is an example of a painting (which in my opinion) could no longer be considered a Haring for two reasons. One, the validity of an A.I.-generated work has not been established. And two, authentication always comes down to the artist’s intent. Keith Haring’s intention was to leave the painting in its incomplete state—it was meant as a comment on the AIDS epidemic.

The ‘Mona Lisa’ at the Louvre in Paris in 2021. Photo by Li Yang/China News Service via Getty Images

4. Whitewash a Painting

Speaking of the Salvator Mundi, one of the more provocative stories to emerge from the controversy was the owner’s blatant attempt to validate his acquisition. The owner, said to be Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, approached the Louvre with an offer to lend his painting. At first, the Louvre’s curators proffered interest. If nothing else, it would have led to a surge in admissions. But the deal fell apart once MBS’s representatives demanded the painting be hung directly across from the Mona Lisa. The unambiguous message would have been that the Salvator Mundi is a Leonardo masterpiece just like the Mona Lisa.

This sort of thing has been going on for years. The quickest way to confer authenticity on a painting is “guilt by association.” If you own a picture where all signs point to it being genuine—but you can’t prove it—your best approach is to find a way to align it with an institution. It doesn’t have to be MoMA or the Met (though that would be good); any legitimate public or university museum will do. By hanging your painting, the institution is conferring authenticity. This is how the Orlando Museum of Art got into trouble with its show of questionable Basquiats. Bear in mind this is not committing fraud. It’s only fraud if the lender and/or the institution have suspicions about a painting’s validity (and the owner’s intention to sell it).

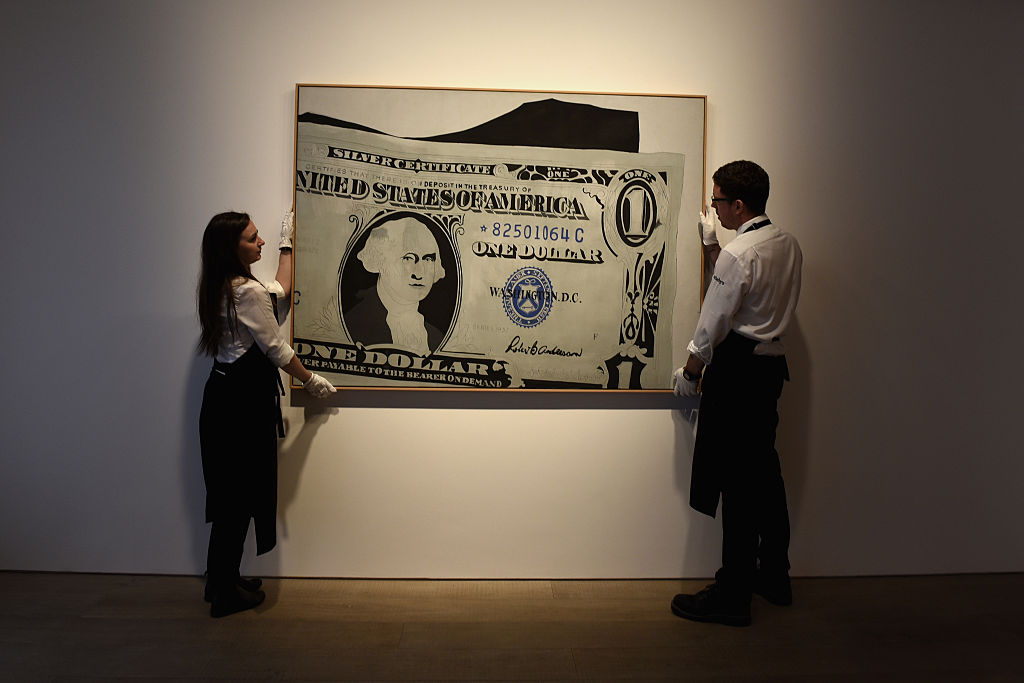

LONDON, ENGLAND -Two art handlers hold Andy Warhol’s Silver Certificate (1962) at Sotheby’s in London in 2015. Photo by Mary Turner/Getty Images

5. When It Comes to Documentation, Less Is More

Scammers go out of their way to create elaborate paperwork. Their logic is that the greater the paperwork, the more likely the painting will pass muster as authentic. Wrong. All this does is create obfuscation. Over time, I’ve been privy to some impressive paperwork, including documents that include so many gold seals and elaborate rubber stamps that they become works of art in their own right.

If you want to commit fraud, one way to do so is by forging an art authentication committee certificate. In recent years, this has become a growth industry. The Andy Warhol market is rife with fake certificates of authenticity from the now-defunct Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. There have also been a blizzard of fake Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat certificates of authenticity, complete with counterfeit Julia Gruen and Gerard Basquiat signatures, respectively.

The trick for a con man is to master the subtleties and nuances of these certificates—which, so, far no one has been able to do. Forgers repeatedly make the same mistakes. They would be well-advised to watch Frank Abagnale, the slippery character played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the movie Catch Me If You Can and learn how to get it right.

Richard Polsky is the owner of Richard Polsky Art Authentication and Richard Polsky Art Fraud Prevention, which specialize in authenticating the work of seven artists: Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Bill Traylor.