Art & Exhibitions

Warhol Wanted This Man, Bad

THE DAILY PIC: The "13 Most Wanted Men" mural, destroyed out of homophobia?

THE DAILY PIC: The "13 Most Wanted Men" mural, destroyed out of homophobia?

Blake Gopnik

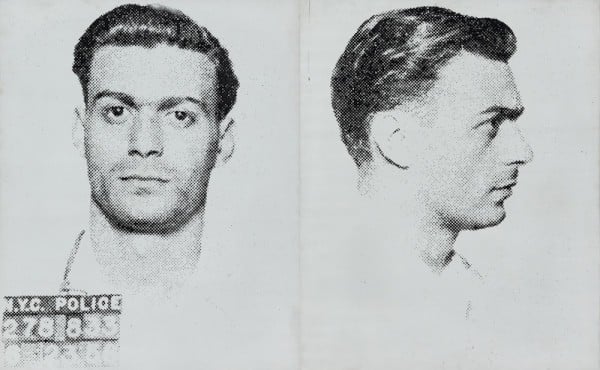

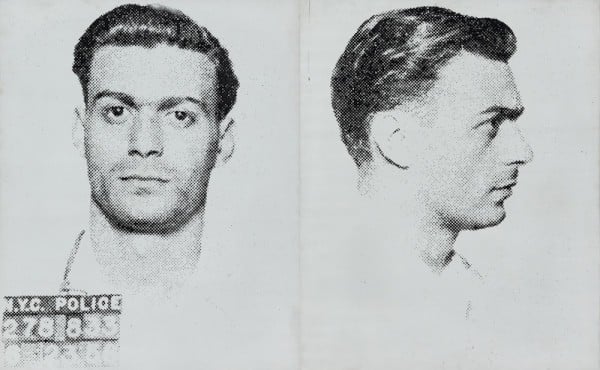

THE DAILY PIC: In July or so of 1964, Andy Warhol remade the silkscreened canvases of his famous “13 Most Wanted Men” mural; this is one of those remakes. The mural had been painted over with silver paint in April, a few days after its 13 “portraits” went up on the facade of the Theaterama building of the New York State Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Queens. A wonderful show about the whole “Most Wanted” affair runs for one more month at the newly renovated Queens Museum, which happens to occupy one of the fair’s original buildings. The exhibition, curated by Larissa Harris, is a model of such things, digging deep into the art in question via the history that surrounds it. You could spend a week unpacking the works and documents in this show, but the Daily Pic can only touch on a bare few of its findings. (You only have to wait another few years to read my full take on the issues, in my forthcoming—eventually—biography of Andy.)

First of all, it’s worth noting that when a pamphlet for the pavilion described the facade as sporting the very latest in “avant-garde” art, it was speaking the truth. Philip Johnson, the famous architect, was in charge of the commissions for the Theaterama facade, and his first approach to Warhol came as early as December of 1962, before the artist had much recognition. (Warhol’s idea for the project had gelled by the following April, so the mural should really be considered a work from early 1963, not ’64. The nine other artists invited included Roy Lichtenstein—who made the project’s only truly site-specific work—as well as Robert Indiana and Ellsworth Kelly.) I think Warhol’s piece, like his entire career, is dedicated to the classic avant-garde aim of breaking rules, both artistic and social. The fact that the mural ruffled feathers so badly gives some idea of Warhol’s success as a rule breaker.

The standard explanation for the destruction has long been that there was felt to be something iffy about this “celebration” of the underdog. Also, that there were too many Italians among the mural’s criminals, and that Governor Nelson Rockefeller didn’t want to risk alienating that important constituency. I have to wonder if the latter makes sense: How would anyone have known the men’s names, let alone that they were Italian, without substantial digging? The “Most Wanted” brochure that Warhol used as his source must have been long out of date, and out of circulation, by the time the mural was unveiled. I think the real issue—such a hot-button that it could not speak its name—was homosexuality. The very idea that men might be wanted, by a male artist no less, was more than a family-friendly World’s Fair could stomach. Better to blame ethnic politics for the destruction of the work than to raise even the specter of gayness.

On March 4, Johnson sent Warhol a worried telegram about the piece, asking him not to comment on it. On April 15, a Long Island newspaper wrote the only report on the newly installed mural, and the writers dropped in a generic reference to “expected howls of protest”. “Things could have been worse,” write the reporters, and then quote Warhol: “I had thought about doing a great big Heinz pickle.” By April 18, the same paper was reporting on the decision to paint over the work: “The ‘pop’ artist … decided yesterday that he doesn’t care about the ‘boys’ either.” Johnson is quoted saying that “there have been some complaints from people who didn’t like the subject matter. But that had nothing to do with the art.”

Warhol’s planning for the piece is steeped in gay culture. Johnson was almost as openly gay as Warhol, and in fact it’s said that his art-savvy lover, David Whitney, was the one really behind the mural commissions. Warhol got his hands on the brochure via the cop boyfriend of a male painter friend, and the brochure’s title, “The Thirteen Most Wanted,” must have tickled his gay funny bone instantly. Its images may have had equal impact: several of the guys it shows are, in fact, notably dishy. Later, after he’d painted over his gangsters, Warhol used a similar title, “13 Most Beautiful Boys,” for a series of filmed portraits of his young hangers on—almost as though he were spelling out the meaning of the vanished work. (He shot way more than 13 of those films, so the only reason to use that number would have been to forge a clear link to the mural.)

The “problem” of homosexuality was very much in the news at that moment. In an effort to “clean up” the city for visitors to the impending fair, officials had embarked on an anti-gay campaign, closing down bars and harassing the queer community. On April 18 itself, the gay writer Frank O’Hara sent a letter about the clampdown to the omnisexual painter Larry Rivers, a close Warhol associate. That’s the same day that the Film-Makers’ Cooperative published a “note to our friends” about how the pre-fair cleanup—which included the arrest of Coop founder Jonas Mekas—was making New York “look like Toronto on a cold winter day.” (As a former Torontonian, I have to issue a formal objection: Toronto doesn’t get all that cold.)

So it looks to me like the same cleanup could easily have extended all the way to the World’s Fair grounds themselves. Of course, it resulted in a decent conclusion, art historically speaking: Warhol’s naughty pictures get replaced with a giant monochrome, the most avant-garde gesture of that moment in art. And, in silver, it acted as a mirror for New York to see itself in.

(Image courtesy Stadtisches Museum Abteiberg, photo by Achim Kukulies; © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive