Art & Exhibitions

How Impressionism Became Expressionism: A New Exhibition Traces Claude Monet’s Influence on the New York School

The Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris juxtaposes 10 works by Monet with 20 by American titans.

The Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris juxtaposes 10 works by Monet with 20 by American titans.

Javier Pes

Abstract Expressionism, the movement that cemented New York’s status as the new center of the art world after World War II, is coming home—to Paris. The quintessentially American art movement’s debt to Europe is the subject of a new exhibition at the city’s Musée de l’Orangerie.

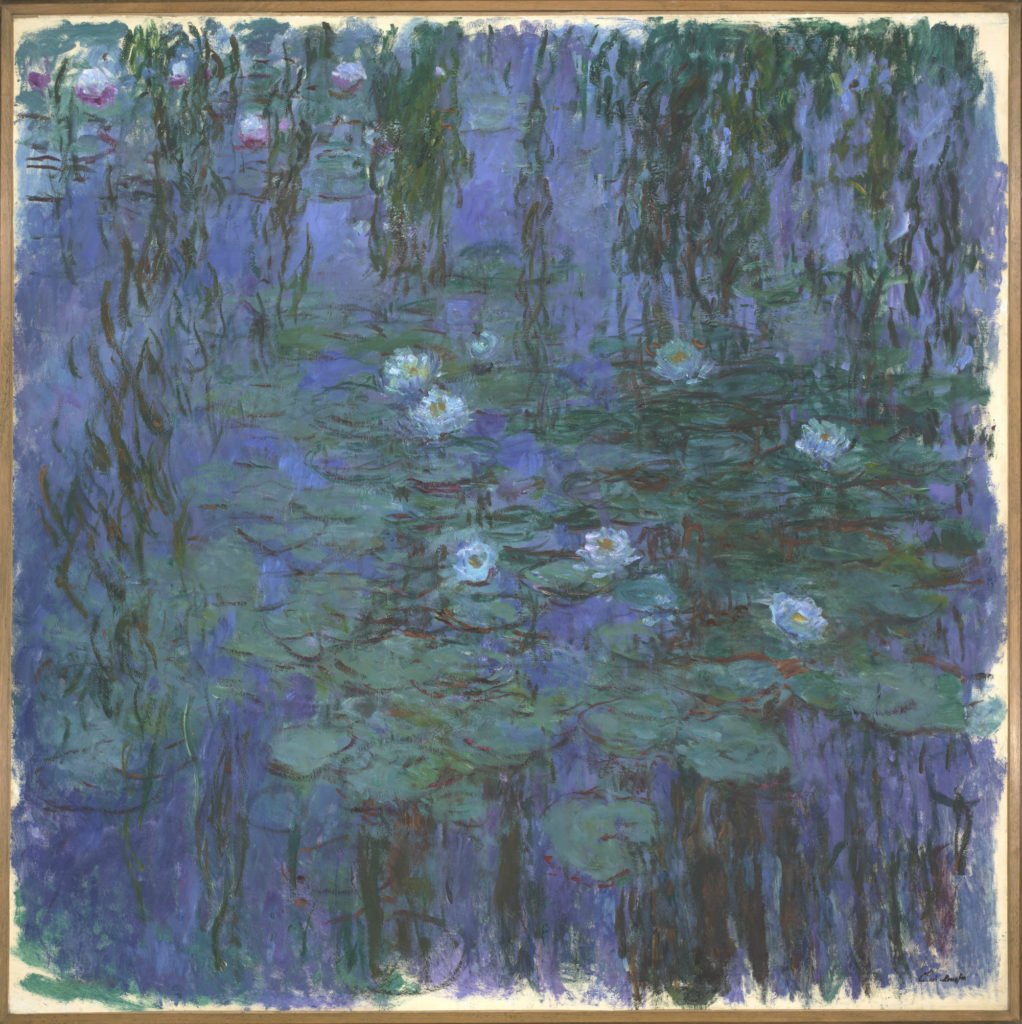

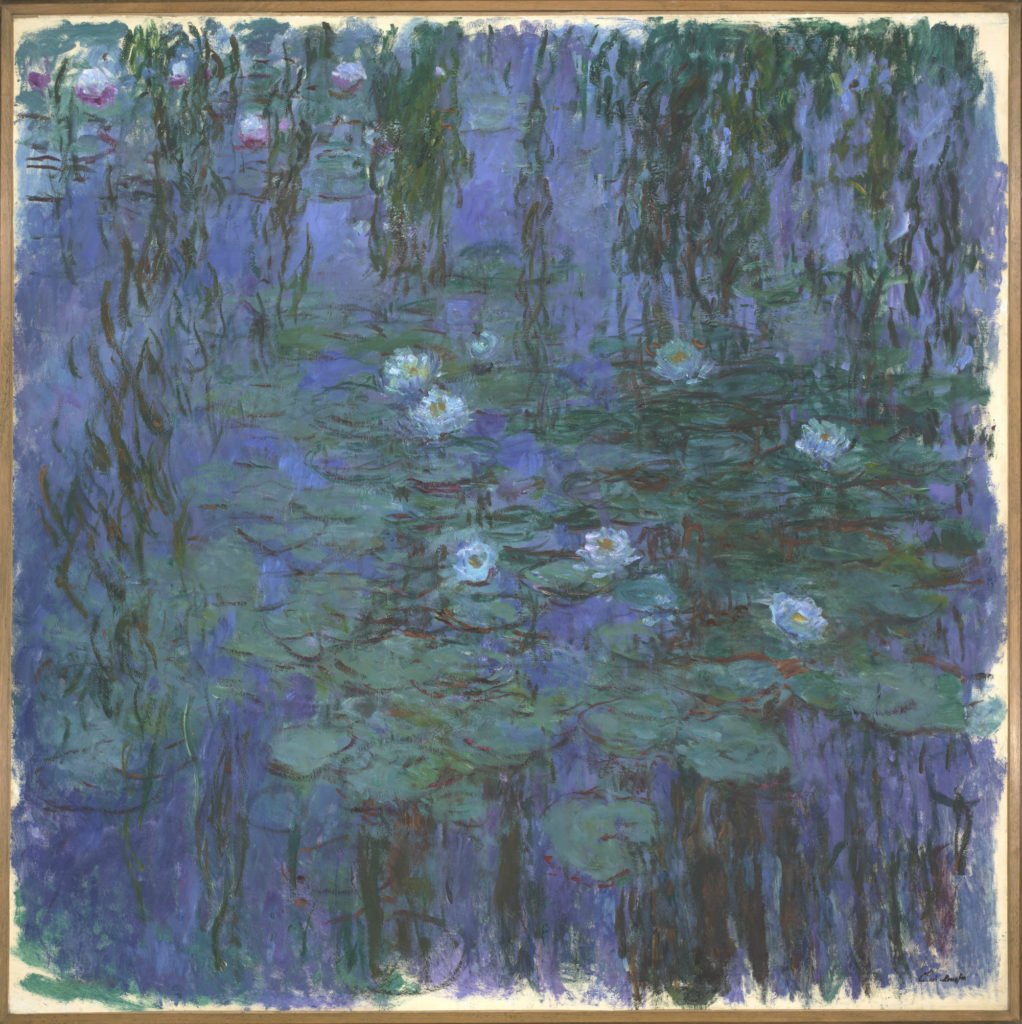

“The Water Lilies: American Abstract Painting and the last Monet,” which opens on April 13, juxtaposes 10 of the French artist’s beloved paintings with 20 major works by American artists including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Barnett Newman. The show will open with a large-scale work by Ellsworth Kelly, who was particularly vocal about Monet’s influence.

The show’s curator Cécile Debray, the chief curator and director of the Musée de l’Orangerie, notes that many American art critics saw Monet as a bridge between Impressionism and the New York School. After Clement Greenberg saw Monet’s water lilies on a visit to Paris in 1954, he opined that both Newman and Clyfford Still were following in the footsteps of the elder French artist.

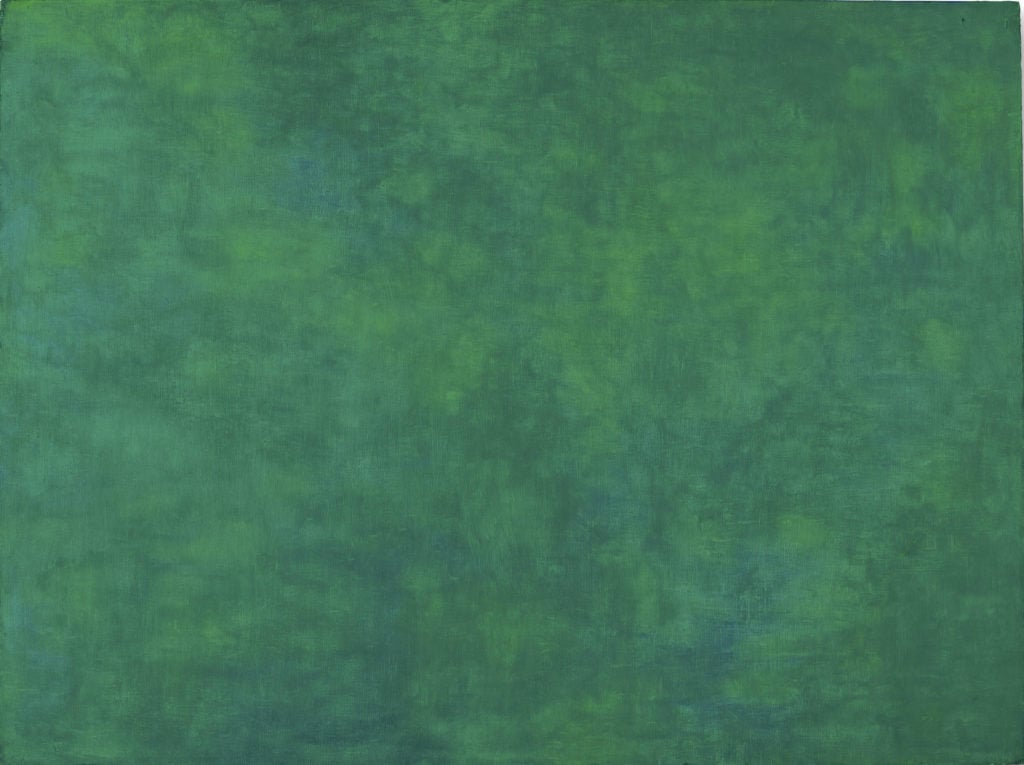

Ellsworth Kelly, Tableau Vert (1952), The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of the artist, 2009 Photograph courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago Artwork, copyright Ellsworth Kelly Foundation.

Indeed, in the years after World War II, Monet’s garden at Giverny and his paintings in Paris became a site of pilgrimage for young American artists studying in France. One of them was Kelly, who saw dozens of the artist’s unsold works on a visit to Giverny in 1952. He was so impressed by their scale and gestural brushwork that he painted an homage: Tableau Vert (1952), now owned by the Art Institute of Chicago, which kicks off the Paris show.

Joan Mitchell’s all-over abstraction was also informed by her exposure to Monet. In 1955, the artist began dividing her time between New York and France, and in 1968, she moved there permanently, buying a home just a few miles from Monet’s in Giverny.

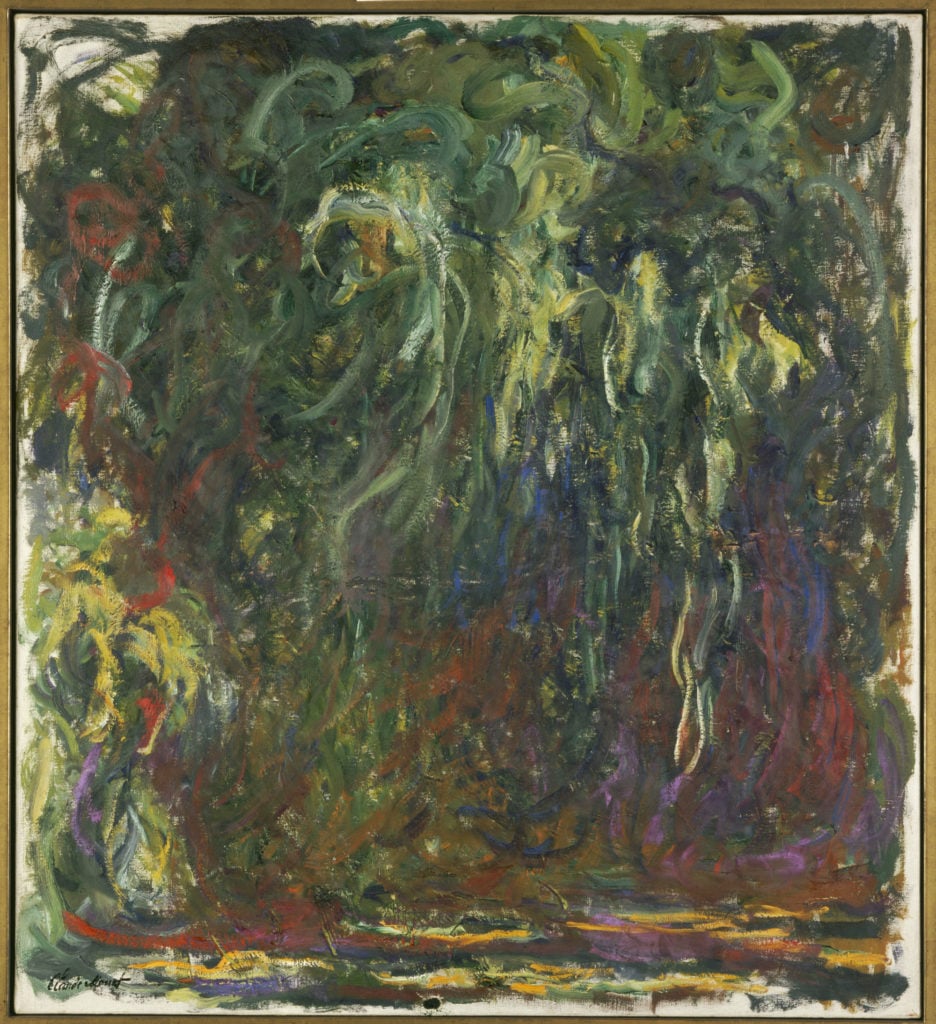

Claude Monet, Le Saule pleureur (1920-22) Musée d’Orsay, donation Philippe Meyer, 2000, Photograph copyright RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Michèle Bellot.

Although it took time for Monet to gain traction in the US, the Museum of Modern Art’s director Alfred Barr belatedly gave his blessing to acquire the museum’s first water lily paintings in 1955—not coincidentally, around the same time that Abstract Expressionism was at the peak of its influence in New York. A stampede of demand followed. Midwestern museums including the Nelson-Atkins in Cleveland and the Minneapolis Institute of Art rushed to buy Monet’s late works the following year.

The Paris exhibition is chock full of large-scale works—many of which are rarely seen together and travel infrequently—by heavyweights including Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Philip Guston, and Sam Francis. Important loans came from New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, among other institutions.

The show is supported by the American Friends of the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Terra Art Foundation.

Philip Guston, Dial (1956). Whitney Museum of American Art, copyright the Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

“Waterlilies: American Abstract Painting and the Last Monet,” runs from April 13 through August 20 at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.