Art World

Was Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ the World’s First 3-D Image?

Sarah Cascone

Leonardo DaVinci’s Mona Lisa (circa 1503–06), displayed behind bullet-proof glass at the Louvre in Paris, is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Less well-known is a copy of the work held at the Prado in Madrid. Now, a scientific comparison of the two paintings suggests that together, they may form history’s first stereoscopic image, reports Design Boom.

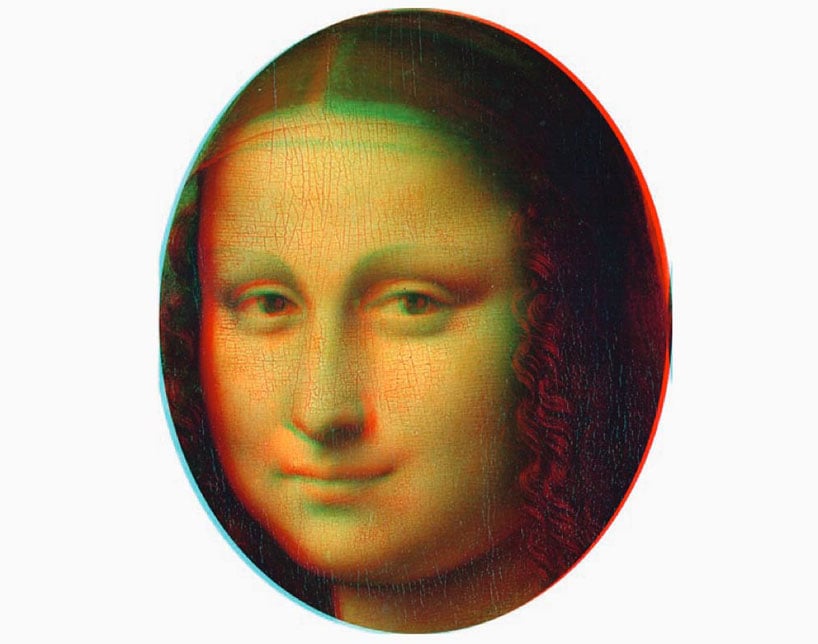

Two researchers, German experimental psychologists Claus-Christian Carbon and Vera M. Hesslinger, have overlaid the iconic painting and its twin, and the resulting red-cyan anaglyph looks uncannily like a 3-D image. The paintings are remarkably similar, although the landscape background is roughly 10 percent larger in the less familiar version of the work.

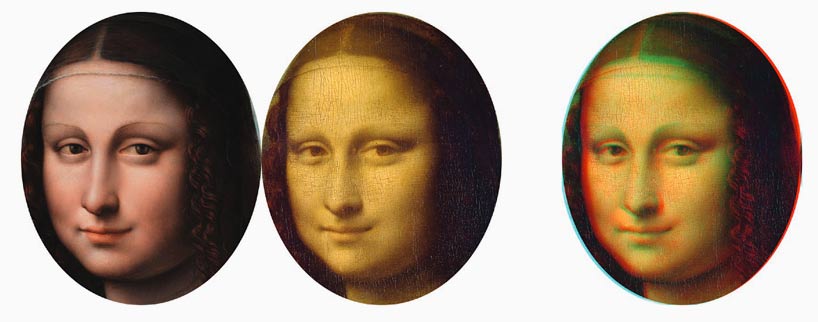

The Prado Mona Lisa, left, and the Louvre version, right.

Long thought to have been the work of a copyist, the Prado Mona Lisa may actually have been painted contemporaneously with da Vinci’s version—indeed, from the very same portrait sitting! The minute difference of perspective between the two paintings, and the slightly enlarged background in the Prado canvas suggest that the two artists were working side-by-side, da Vinci a few steps behind the anonymous painter. A landscape motif canvas stood in for the backdrop, accounting for the smaller scale in the master’s work.

“We reconstructed the original studio setting and found evidence that the disparity between both paintings mimics human binocular disparity,” explained German scientists. “This points to the possibility that the two giocondas together might represent the first stereoscopic image in world history.”

The Prado Mona Lisa, left, the Louvre version, center, and the combined red–cyan anaglyph stereoscopic version, right.

In their report, Carbon and Hesslinger also claim to have discovered that the two paintings “share several corrections also in the tracing and lower paint layers,” bolstering their conclusion that the two canvases were simultaneously executed. In 2012, the New York Times also reported the likelihood that the two paintings were done at the same time.