Art History

Watteau’s Beloved Depiction of Dreamy Aristocratic Love is a Rococo Gem. Here Are 3 Things You May Not Know About It

This month marks the 300th anniversary of Jean-Antoine Watteau's death.

This month marks the 300th anniversary of Jean-Antoine Watteau's death.

Katie White

Outdoor celebrations—mythological bacchanals, picnics, and the like—have been a favorite subject of artists for centuries, as you already know if you’ve been keeping up with us. And among the best at capturing lavish outdoor frolicking, especially of aristocrats, was the French Rococo artist Jean-Antoine Watteau. He not only made a career of it, he practically founded a whole new genre.

Among his most famous paintings is the Embarkation to Cythera (1717), which shows opulently dressed couples waiting to board a golden gondola (more on that soon). The painting was heralded in its day, as it depicted a period of joyful insouciance after the dark year following the death of Louis XIV. But the era Watteau captured (or perhaps imagined) was brief, and as the ancien regime began its long collapse, Embarkation to Cythera came to be seen as the embodiment of the kind of out-of-touch indulgence that French Revolutionaries could not bear. (The Louvre went so far as to hide the painting for its protection.)

Nevertheless, by the mid-19th century, there soon emerged a nostalgic view of the picture, with viewers and writers pining melancholically for its sweet innocence (even if that innocence was just a figment of aristocratic imagination).

Watteau didn’t live long enough to see that moment come to pass: his exuberant career was cut short when he died at the age of 36 on July 18, 1721.

To mark the 300th anniversary of his death—and to give us all a bit of summer park hang inspo—we decided to take a closer look at this unabashedly idyllic painting. Here are three surprising facts that might make you see the Embarkation to Cythera in a whole new way.

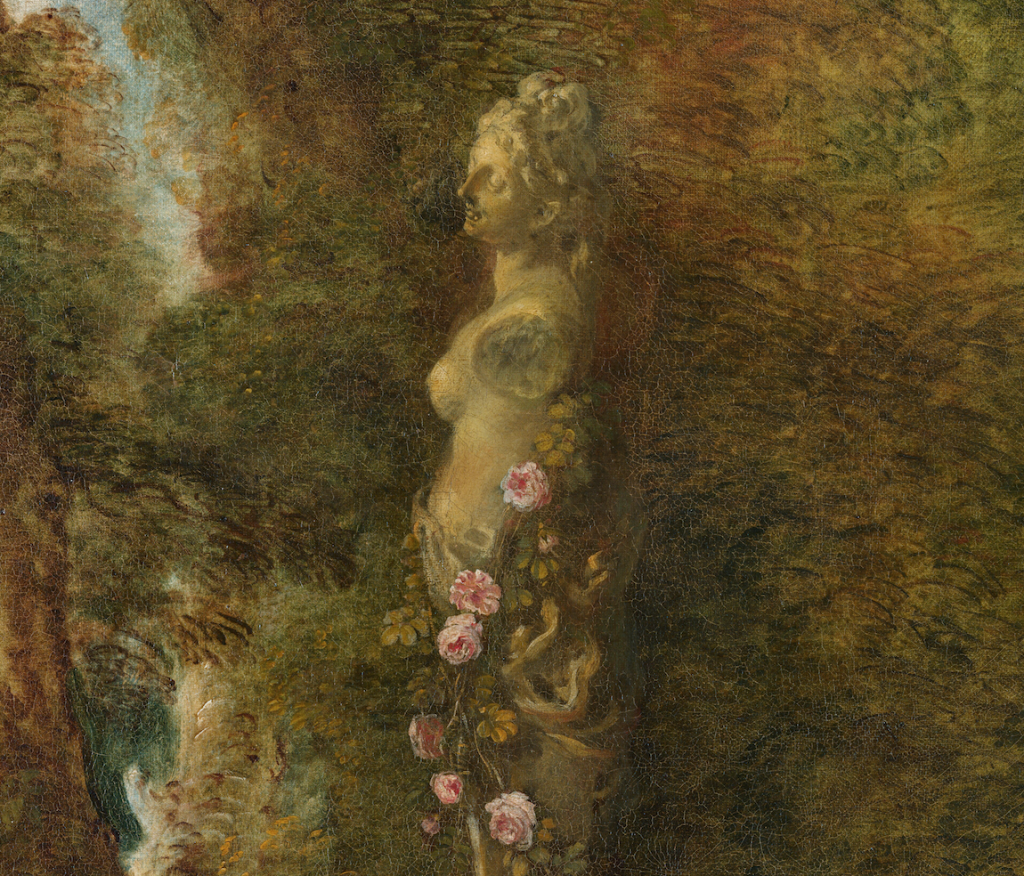

Detail of Jean-Antoine Watteau’s The Embarkation for Cythera (1717). Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

Embarkation to Cythera came after years of procrastination on the part of Watteau. In some senses, he was forced to paint it.

Accepted to the Academy in 1712, Watteau was expected to mark the accolade by submitting a picture. Unlike most artists, the Academy allowed Watteau to pick any subject of his liking. But rather than set to work, Watteau spent the next five years completing numerous commissions that buoyed his growing reputation.

In January 1717, the Academy finally called the artist to task and demanded the work. That August, Watteau presented his splendid, if hastily wrought, Embarkation to Cythera. (He also made two more versions of the painting, one earlier in 1717, now in the collection of Städtische Galerie in Frankfurt, and another in 1719, which is on view at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin).

The painting delighted the Academy even as it defied its neat categorizations, forcing its trustees to invent a new classification to describe it: fête galantes. The genre features wealthy men and women in the most elegant of fashions, amorously canoodling in wooded parks. Later, it became synonymous with the Rococo. Yet despite the work’s positive reception, the painting failed to earn Watteau the most esteemed title, that of history painter.

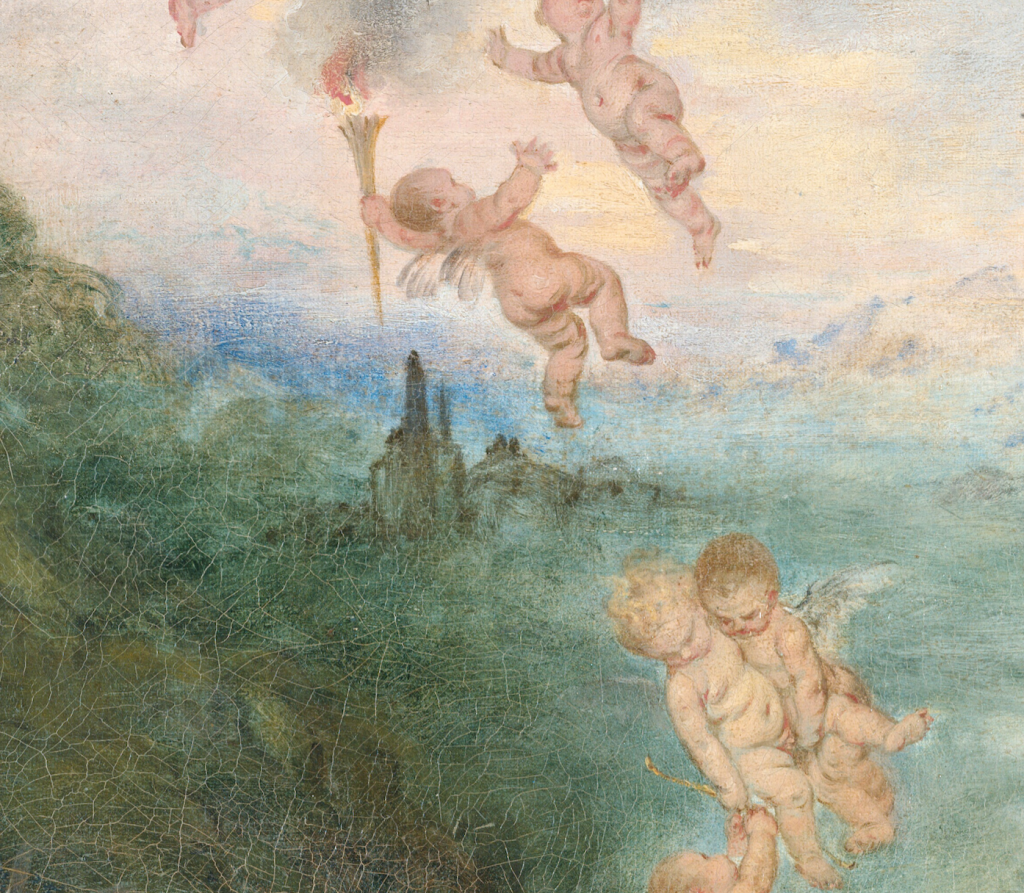

Detail of Cupid with his quiver beside an amorous couple. Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

Ambiguity is the defining trait of Embarkation for Cythera. For decades, scholars have argued back and forth over whether this well-heeled party is truly departing for Cythera, the mythological birthplace of Aphrodite, or about to depart from the island, which is so associated with love. And it’s not hard to understand the confusion. The setting in which these myriad couples appear is adorned with many attributes of the goddess, including a statue of her likeness wrapped in roses.

Many scholars argue that this detail of a sculpture of Aphrodite means the party is about to leave Cythera—not embark for it. Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

Cupid, meanwhile, appears at the side of one demure young woman and seemingly nudges her towards love, perhaps suggesting that they have already arrived.

Meanwhile, a cluster of cherubs swirling over a gondola seems to be encouraging these amorous couples towards an island in the distance.

Detail of what might be the island of Cythera in the distance(1717). Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

This confusion may have been productively intentional, and Watteau refused to elaborate on the composition. Still, others have interpreted the ambiguity as reflective of the dance-like experience of courtship. They say these varied phases—from uncertainty to embrace—show the progress a couple takes from shy conversation (at the right-most of the scene) to the embrace of the more mature couple about the step onto the boat.

Is the golden gondola in The Embarkation for Cythera a reference to Venice? Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

A wondrously unreal quality suffuses the painting, as wispy clouds in a hazy blue sky, set against an immense and dramatic landscape, give no sense of season or time of day.

It’s possible Watteau was looking at Greek mythology for inspiration. Or maybe he was looking much more close to home.

Watteau was fascinated by the commedia dell’arte, as evinced by his famed painting Pierrot of the following year. Here, his fascination is with theater surfaces, and the composition, which appears like a stage set, depicts a cascading procession of elaborately costumed actors receding into the background.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pierrot (1718). Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

Some historians have suggested that the theme of the painting may have been suggested by the play Les Trois Cousines by Florent Carton Dancourt, in which a voyage to Cythera is undertaken. Houdar de la Motte’s 1705 opéra ballet of La Vénitienne (1705) may more likely have been the inspiration: the production features a pilgrimage to Cythera, but also includes the commedia dell’arte characters Watteau took such interest in. In this reading, the golden gondola in the background may be a reference to La Serenissima, the haven we also call Venice.