Pop Culture

The Real-Life Artists Behind ‘The French Dispatch’ Share What It Was Like to Paint for Exacting Auteur Wes Anderson

The team studied up on Félix Vallotton and scurried to find out-of-season cherries.

The team studied up on Félix Vallotton and scurried to find out-of-season cherries.

Sarah Cascone

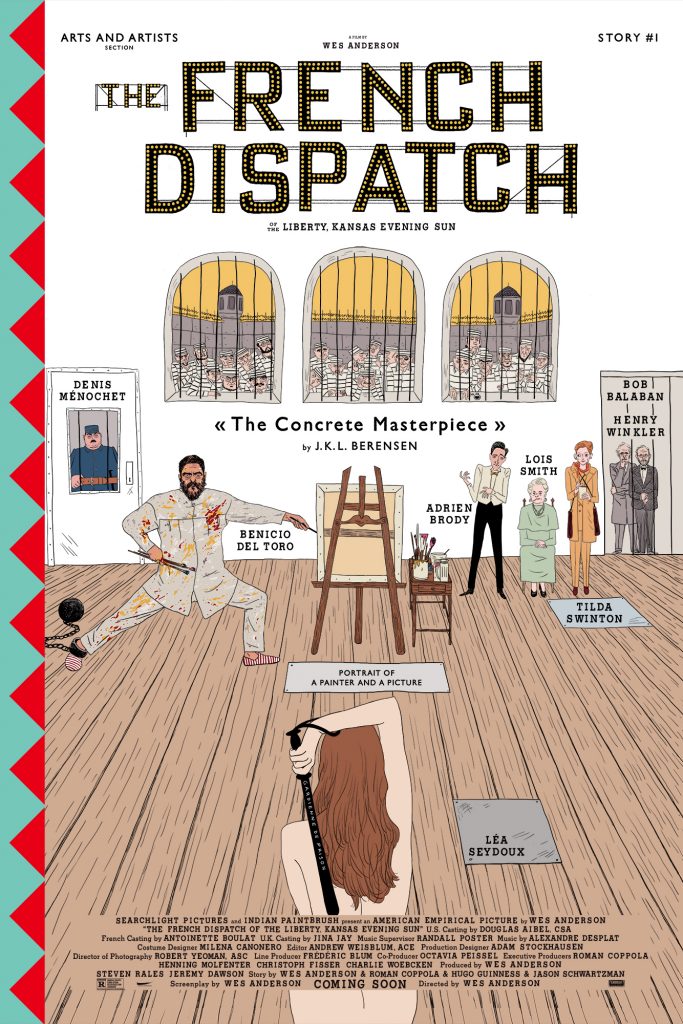

The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, the latest effort from noted auteur Wes Anderson, transports viewers to the mid-20th-century French village of Ennui-sur-Blasé in an anthology film where each chapter represents a feature article in the titular New Yorker–style magazine (complete with covers by illustrator Javi Aznarez).

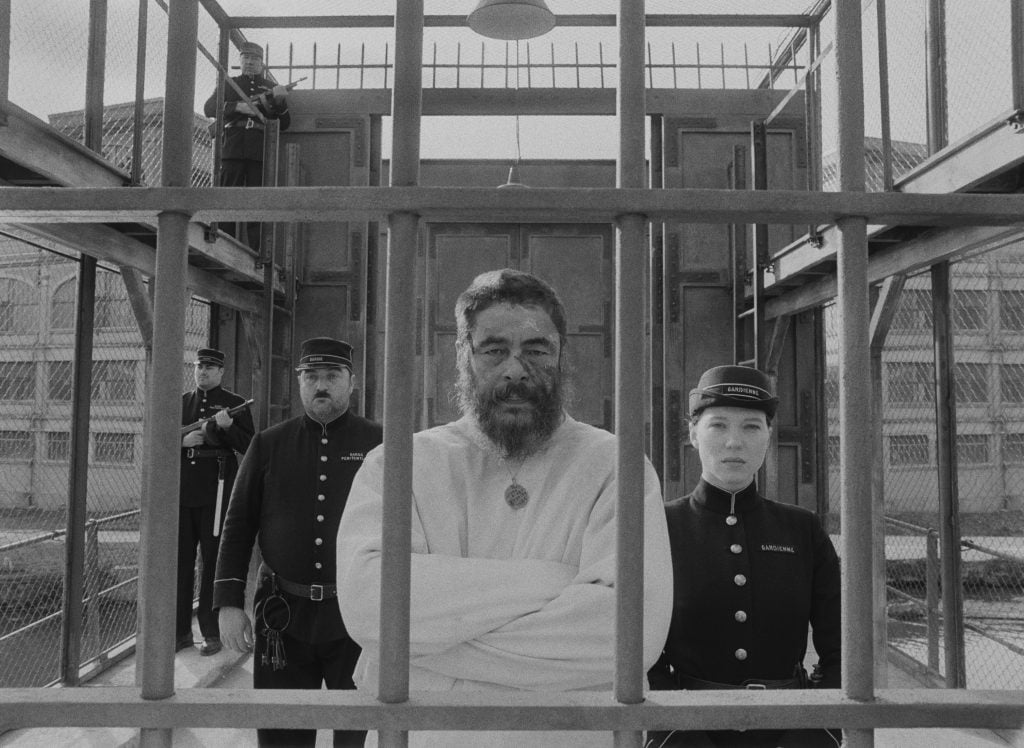

One of those stories is “The Concrete Masterpiece,” told in the form of an art lecture by staff writer J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton), a character inspired by art historian Rosamund Bernier. It’s about Moses Rosenthaler (played, at different ages, by Benicio del Toro and Tony Revolori), who becomes a world-renowned artist while serving a murder sentence at the Ennui prison.

To bring the character to life, Anderson enlisted a trio of IRL artists—Sandro Kopp assisted by Sian Smith and Edith Baudraud—to execute Rosenthaler’s on-screen oeuvre, which includes early paintings in a more traditional figurative style that make way for the radical abstractions made during his incarceration.

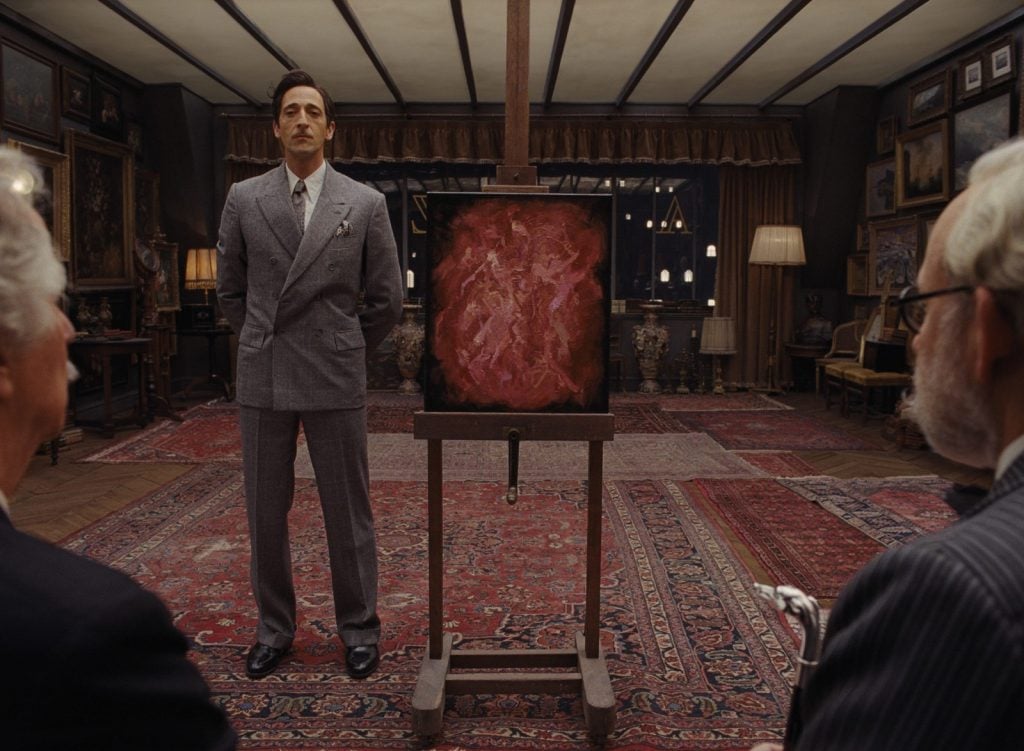

It is one of these later works, Simone Naked, Cell Block J Hobby Room, that catches the eye of another inmate, Julian Cadazio (Adrien Brody), an art dealer serving time for tax evasion. (Rosenthaler’s prison guard-turned-lover, Simone, played by Léa Seydoux, is the model.)

Cadazio convinces a reluctant Rosenthaler to let him represent him—“It’s what makes you an artist. Selling it”—and quickly turns him into an art-world sensation, irresistible not only for his groundbreaking artistic vision, but also for his mental illness and violent tendencies.

It was up to Kopp’s team of artists to create paintings that lived up not only to that vibrant backstory, but also satisfied Anderson’s exacting eye for detail and distinctive filmmaking style.

“Wes has known my work for awhile—he hosted a show of mine at Lehmann Maupin in 2012, and we’ve been mates,” Kopp, also Swinton’s partner since 2004, told Artnet News. “He knew I’ve painted both abstractly and figuratively, and I’ve also worked in film in a variety of different capacities before.”

Adrien Brody as Julian Cadazio with Moses Rosenthaler’s Simone Naked, Cell Block J Hobby Room in The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

That included doing an onscreen painting for one of Swinton’s films, Okja, directed by Bong Joon-ho in 2017. But creating an entire career’s worth of work for Rosenthaler was a project of an entirely different scale that he knew he couldn’t tackle alone.

Enter Smith, who had met Kopp in 2010 on the set of We Need to Talk About Kevin, also starring Swinton. Director Lynne Ramsay had enlisted then 18-year-old Smith, who is her niece, to act as an assistant for a couple of weeks—a gig that ended up lasting for the three-month shoot.

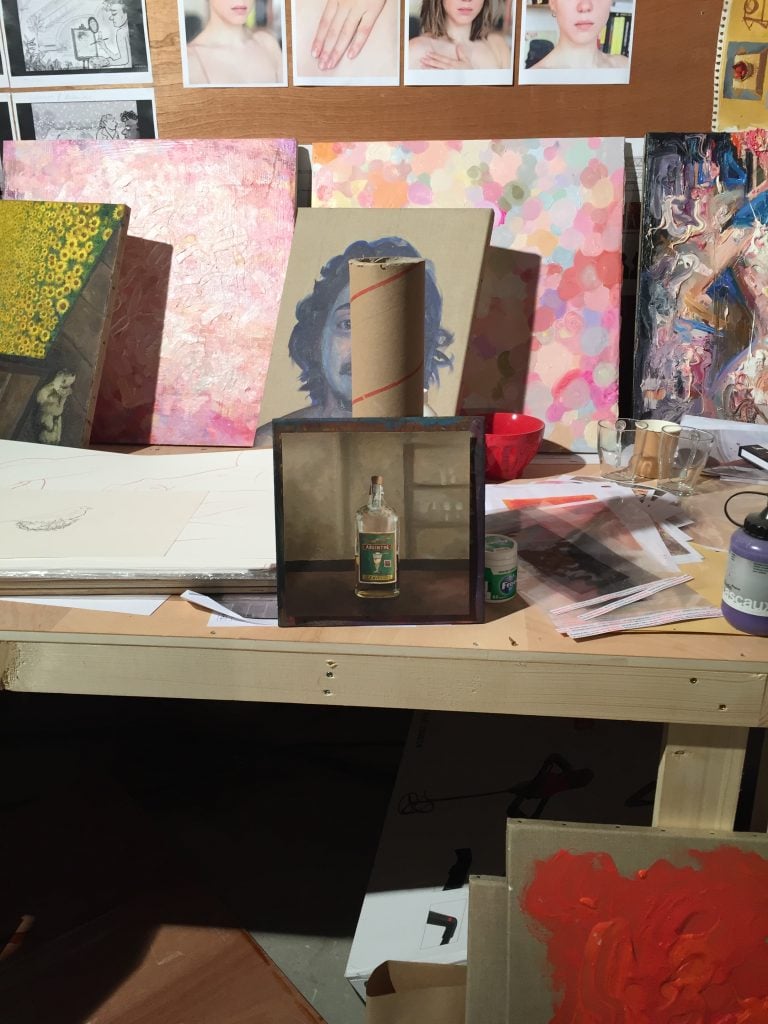

Kopp called Smith up shortly after she graduated the New York Academy of Art in 2018. Within a week, she was on a plane to Angoulême, France, where production on The French Dispatch took place in an old felt factory.

Sian Smith making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

“I’m a huge Wes Anderson fan, so obviously I jumped at the opportunity,” she told Artnet News. “It was this crazy busy environment, but so creative and very inspiring.”

Fresh off the intensive oil painting curriculum at the academy, Smith was tasked with creating Rosenthaler’s smaller early works. With Baudraud’s assistance, Kopp took on Simone Naked, as well the 12-foot frescoes that are the artist’s late masterpiece—and feature in the story’s dramatic climax, in which Cadazio bribes the prison guards to stage a hotly anticipated reveal for a select group of wealthy art collectors. (Cadazio is inspired by dealer Joseph Duveen, and the main collector, Upshur “Maw” Clampette, played by Lois Smith, by Dominique de Menil.)

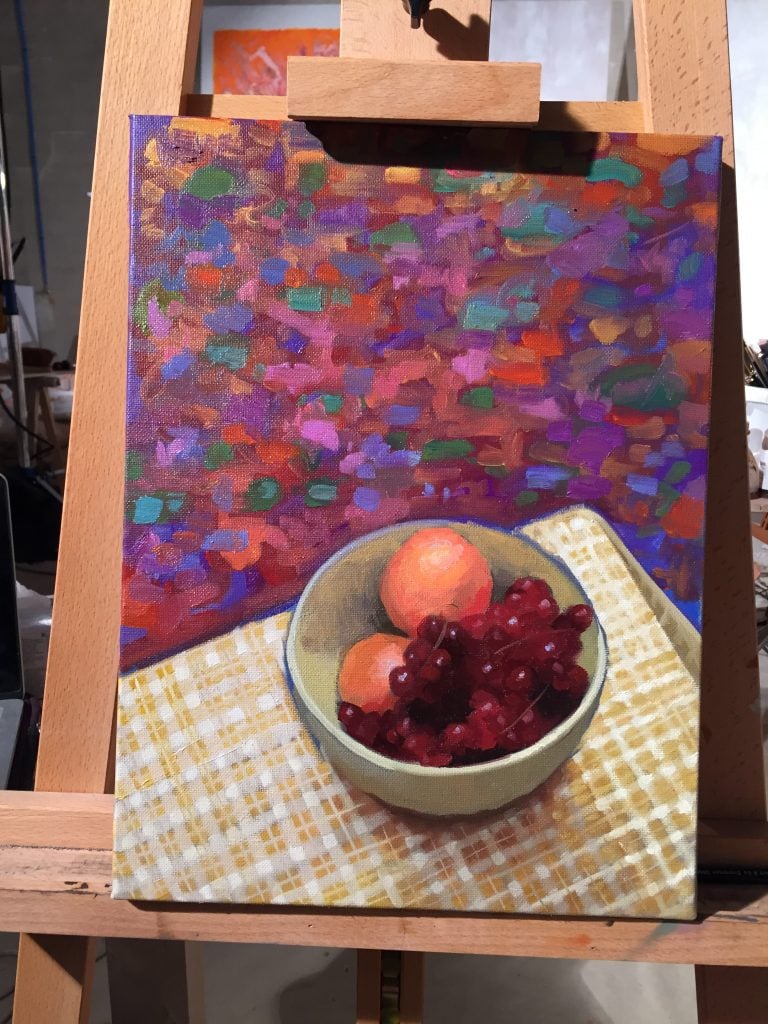

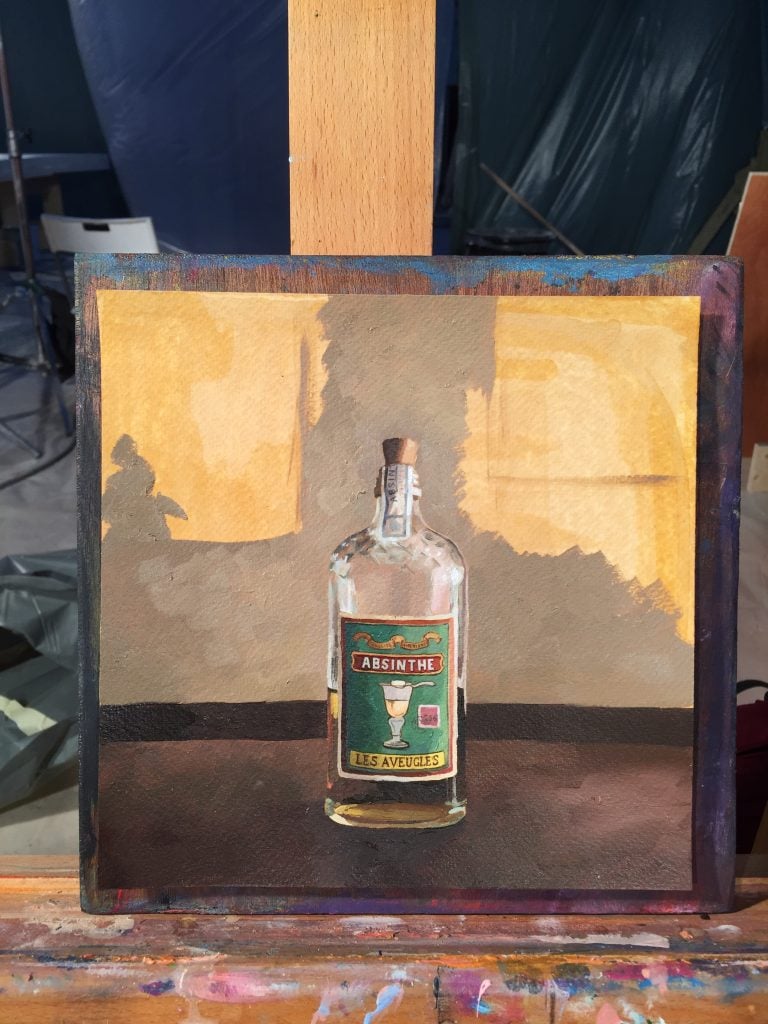

The artists worked for over a month on the production. Anderson provided the basic storyboard images, but wanted the figurative works, inspired in part by the work of Swiss painter Félix Vallotton, to be painted from life—which sent Smith on a wild goose chase, looking for out-of-season cherries to finish Rosenthaler’s The Fruit Bowl.

Sian Smith, Sandro Kopp, and Edith Baudraud with the paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Couldn’t they have just worked from a photograph as a reference, you might wonder?

“No, no, no, no, not on this production,” Kopp said.

“I spent a day wandering around the tiny town trying to find them, and I asked the props department to look when they were going to Paris,” Smith said. “In the end, we couldn’t find any cherries, so we used red currants!”

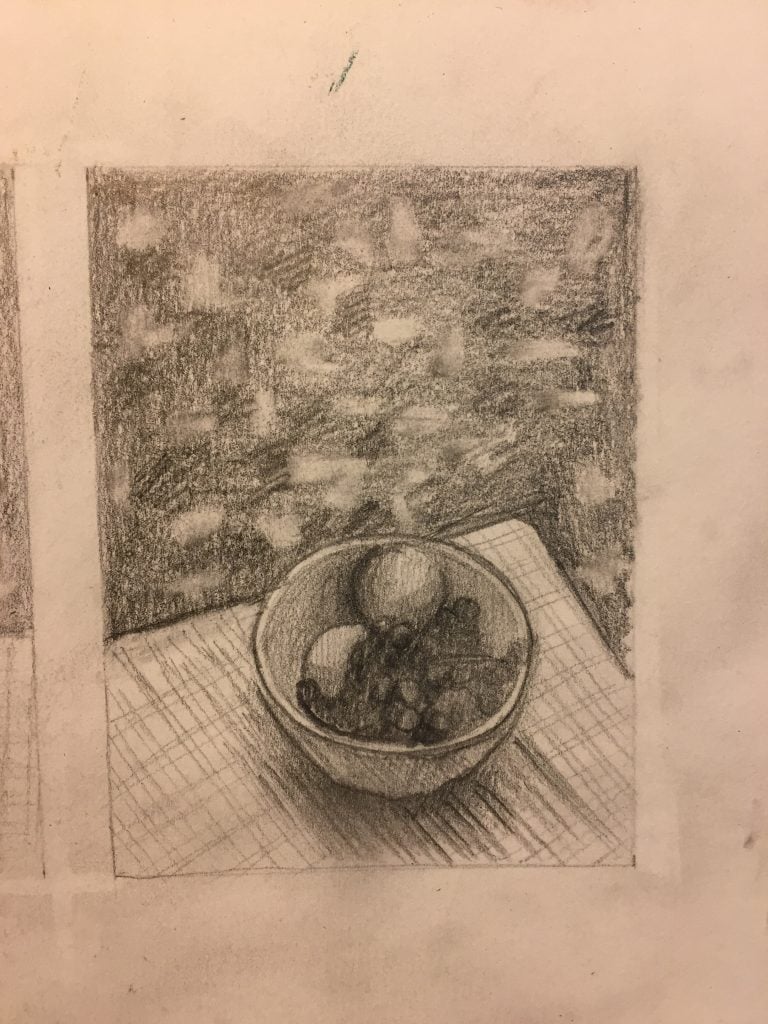

For each painting that appeared on-screen, the artists had to work and rework the composition to meet Anderson’s exact specifications.

The Fruit Bowl, Sian Smith’s Moses Rosenthaler painting for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

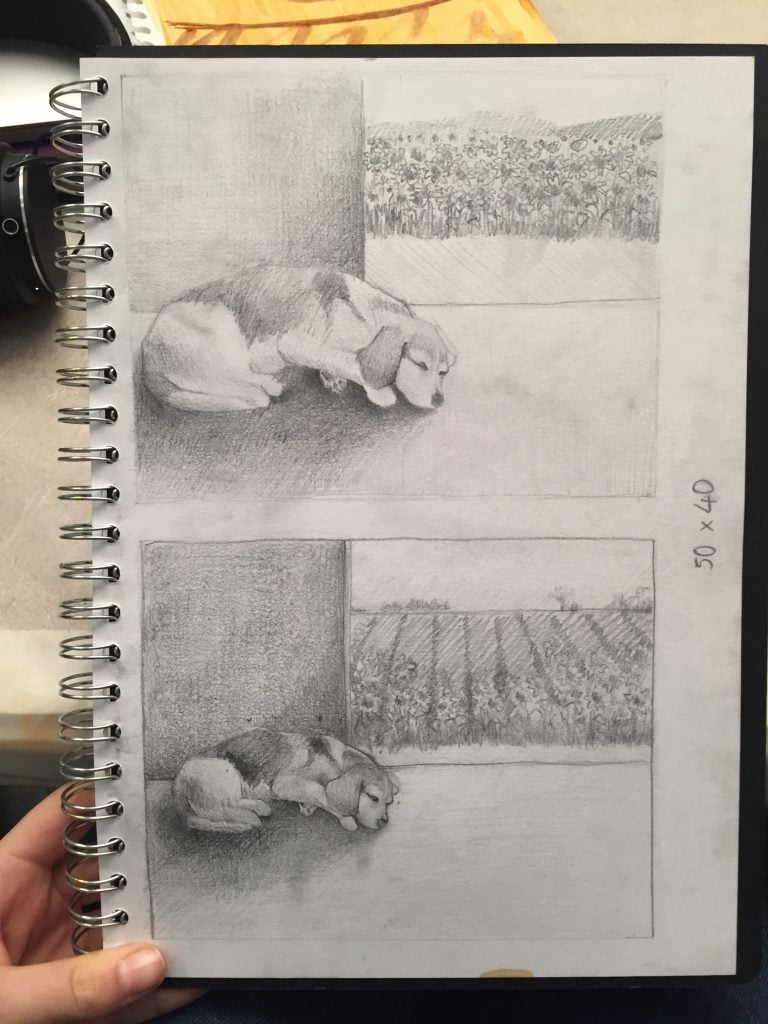

“Wes had this really clear idea in his head. He knew exactly what he wanted—we did so many sketches for each painting,” Kopp said. “I did nine different versions of Simone Naked, Cell Block J Hobby Room.”

When it was time to finally shoot the piece, Kopp still felt the work that wound up on screen was unfinished. Convinced he could do even better, Kopp actually continued reworking the composition after filming ended, since a new painting could be swapped in during post-production—but Anderson ultimately kept the one used on set in the final product.

Even more demanding was The Perfect Sparrow, a tiny drawing Rosenthaler is said to have completed “in 30 second with the burnt-off end of a matchstick,” according to the script. But when Kopp asked Anderson what he had in mind, the director pulled up an incredibly detailed Dürer etching.

One of Sian Smith’s Moses Rosenthaler preparatory drawings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Kopp estimates he drew some 50 sparrows, with Anderson cherry-picking the perfect elements—the wing, the shadows, the head—from different versions and compositing them in a final drawing that would be the perfect Perfect Sparrow.

“And then I watched the film, and it’s not my sparrow! Wes said ‘I liked your sparrow, but it didn’t read on the screen.’ I don’t even know who did the final sparrow,” Kopp said. “It was hilarious!”

Making Rosenthaler’s large-scale late works, on the other hand, had a very different process.

“It was about a very instinctive, visceral, almost violent way of painting—headphones on, buckets full of paint. There were broken brushes,” Kopp said. “I was just trying to be a channel for raw energy.”

Sandro Kopp making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo by Sian Smith.

That process had its challenges too, however: the work had to be entirely redone when the first version didn’t dry properly, causing the thick paint to crack and fall off. To meet the tight production deadlines of the film set, Smith helped Kopp and Baudraud bring the works to completion.

Today, the artworks that made it into the final film are on view at 180 the Strand in London, in an exhibition of French Dispatch costumes, sets, and props. And for the paintings that didn’t make the cut, Kopp has an upcoming show titled “Desperately Seeking Simone” at Berlin’s Ebensperger gallery—it turns out that bringing Rosenthaler to life has become the next step in his own personal practice.

“They do feel like my paintings, and I have continued to work in that manner,” Kopp said, noting how inspirational the movie had proved for him. “The film touches on some emotional and deep truths about what it means to be an artist. The story is beautifully crafted and beautifully written.”

See more from the film below.

The Moses Rosenthaler’s “Concrete Masterpiece” by Sandro Kopp with Sian Smith and Edith Baudraud at “The French Dispatch Exhibition” at 180 the Strand in London. Photo courtesy of 180 the Strand, London.

Moses Rosenthaler props from The French Dispatch, including Simone Naked Cell Block J Hobby Room by Sandro Kopp at “The French Dispatch Exhibition” at 180 the Strand in London. Photo courtesy of 180 the Strand, London.

Tilda Swinton as J.K.L. Berensen with Moses Rosenthaler’s paintings in The French Dispatch. Photo by courtesy of Searchlight Pictures © 2021 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved.

Making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Sian Smith with one of her drawings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Benicio del Toro (center) as incarcerated artist Moses Rosenthaler in The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Sandro Kopp making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo by Sian Smith.

One of Sian Smith’s Moses Rosenthaler paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Tilda Swinton as J.K.L. Berensen with Moses Rosenthaler’s paintings in The French Dispatch. Photo by Sandro Kopp.

Sian Smith making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo by Sian Smith.

One of Sian Smith’s Moses Rosenthaler paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Sandro Kopp making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo by Caris Yeoman.

Moses Rosenthaler paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Adrien Brody as Julian Cadazio and Benicio Del Toro as Moses Rosenthaler in The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Sandro Kopp working on the artwork for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

The painting studio for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Sandro Kopp working on the artwork for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

One of Sian Smith’s Moses Rosenthaler preparatory drawings for The French Dispatch. Photo courtesy of Sian Smith.

Sandro Kopp making paintings for The French Dispatch. Photo by Caris Yeoman.

The French Dispatch. Image courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

“The French Dispatch Exhibition” is on view at 180 the Strand, Temple, London, October 14–November 14, 2021.

Sandro Kopp will give a free artist talk about his work on the film, and his career in general, at the New York Academy of Art, 111 Franklin Street, New York, at 6 p.m. on November 9, 2021.