What I Buy and Why

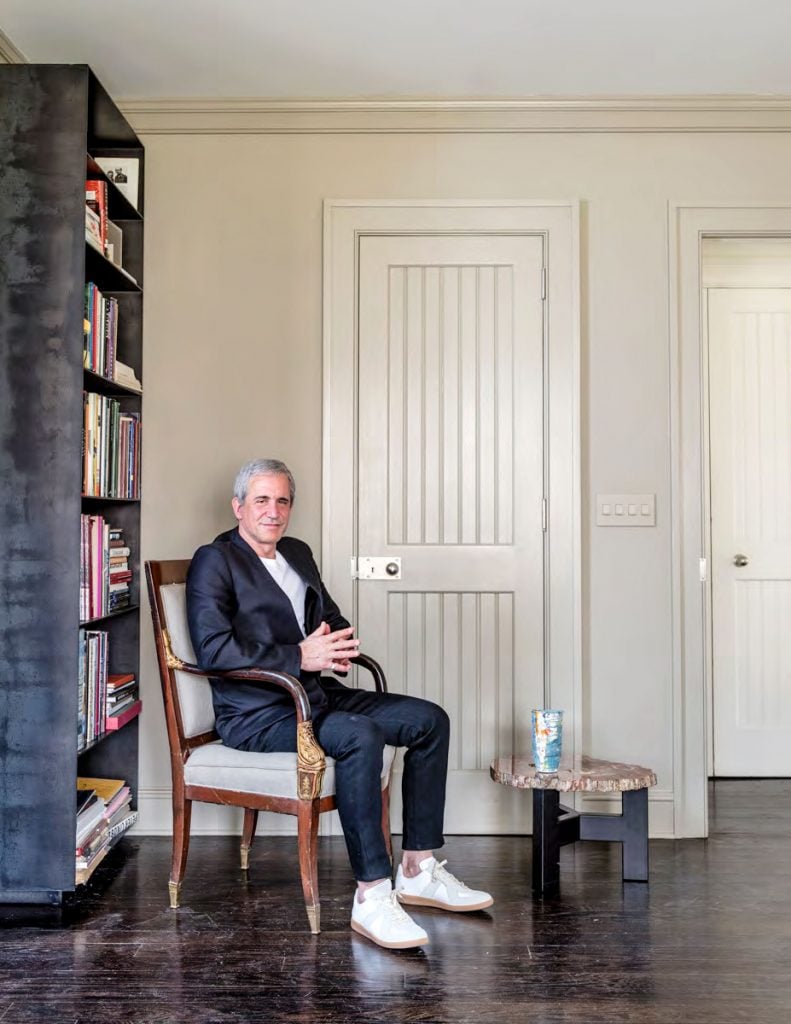

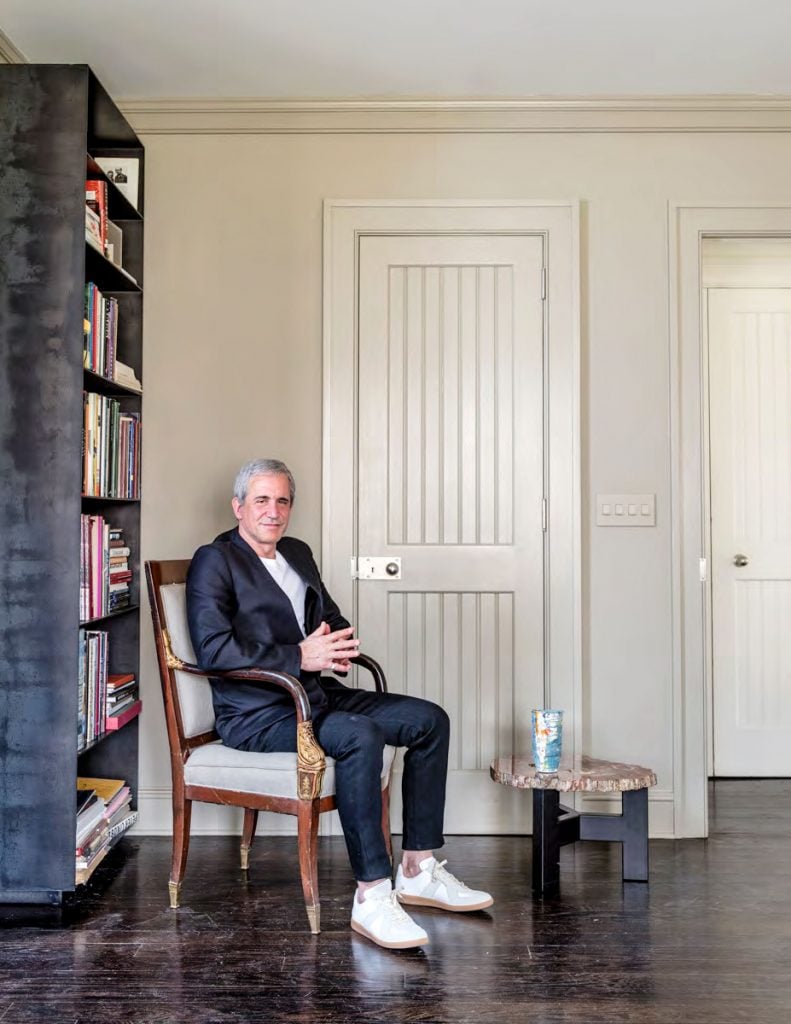

Creative Director Dennis Freedman on His Never-Ending Quest for Avant-Garde Italian Design

An exhibition highlighting more than 50 pieces from his collection will open April 20 in New York City.

An exhibition highlighting more than 50 pieces from his collection will open April 20 in New York City.

Lee Carter

Dennis Freedman, founding creative director of W magazine and former creative director of Barneys New York, embarked on his collecting journey during work trips to Europe in the late 1990s. In the ensuing 25 years of visiting auction houses and befriending furniture dealers across the continent, he’s emerged as a significant collector of avant-garde and experimental designs, particularly Italian Radical furniture design of the late ‘60s and ‘70s. He often makes his acquisitions early in a designer’s career, when prototypes or scale models are still available rather than finished works.

Fernando and Humberto Campana, Sushi Sofa (2003) prototype, in Dennis Freedman’s East Hampton living room, which also features a painted panel (ca. 1969) by Archizoom Associati, Gerrit Rietveld’s Pair of Zig-Zag Chairs (ca. 1950), and a 1967 Ico Parisi table. Photo: Stefan Ruiz. Courtesy of Dennis Freedman.

In the early 2000s, Freedman discovered Brazilian brothers Humberto and Fernando Campana after seeing their work at MoMA and ventured to São Paulo to meet them, as well as scoop up a prototype of Sushi Sofa (2003). Freedman also became enamored with the new crop of Dutch designers—e.g. Joris Laarman and Jeroen Verhoeven—and acquired their work before they were represented by galleries. Freedman further developed a passion for Surrealist furniture created by overlooked women artists, such as Martine Boileau and Marie-Claude de Fouquieres.

Between April 20 and August 11, 2023, design gallery R & Company will showcase more than 50 highlights from the Dennis Freedman Collection. These include Joris Laarman’s aluminum Bone Chair (2006), acquired directly from the designer; an original Locus Solus pool lounger (1964) by Gae Aulenti, Deborah Thomas’s Chandelier (ca. 1983), constructed from glass shards; and Alessandro Mendini’s Monumentino da Casa (1974), one of three surviving examples of the famed non-chair.

Alessandro Mendini, Monumentino da Casa (1974). Wood and laminate. Courtesy R & Company.

We asked Dennis Freedman to catch us up on his adventures in collecting…

What was your first purchase?

My first purchase was an early production (ca. 1972) of the Capitello lounge chair by Studio 65, which I bought in 1998 at an auction at Christie’s South Kensington. It was the first sale of Italian Radical design organized by the 20th-century expert Simon Andrews, and I happened to be in London at the time. This was long before online sales!

There were very few collectors of this critical work, and I realized that I had the opportunity, on a very modest budget, to build a substantial collection. It took 20 years, but I managed to do it. Many of the Italian Radical works in my collection have now been acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

I paid around $5,000 for that purchase, and it remains in excellent condition, with a beautiful golden patina that it has acquired through time.

Studio 65, Capitello (ca. 1972–1978). Polyurethane foam and Guflac. Photo: Brad Bridgers. Courtesy of Dennis Freedman.

What was your most recent purchase?

Along with 20th- and 21st-century European design, I have been buying the work of younger artists, including Jessi Reaves, Anicka Yi, Josh Kline, Alex Da Corte, Woody De Othello, among others. My most recent purchase was a 2021 video work titled Soliloquy, by Martine Syms. I closely follow the programs of gallerists like Oliver Newton and Margaret Lee at 47 Canal, Todd von Ammon, Brendan Dugan at Karma, and the brilliant Bridget Donahue.

Martine Boileau, Table and Four Chairs (1960). Norsodyne polyester resin and glass fibers. Courtesy of R & Company.

Tell us about a favorite work in your collection.

I am most excited when I discover the work of an artist that has been overlooked or under-appreciated. In the storage room of the great Parisian dealer Yves Gastou, I found a game table and four chairs made in bronze-tinted resin by the French sculptor Martine Boileau. It had been in the collection of Elie de Rothschild and was included in the landmark 1962 exhibition “Antagonismes 2: l’objet” at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. If Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse had collaborated on a suite of furniture, I imagine it would have looked like this. It has not been seen in public since. I am very excited to have it included in the upcoming exhibition of my collection at R & Company.

Which works or artists are you hoping to add to your collection this year?

I think I would give up everything to have one of the early ceramic totems by Ettore Sottsass, which were first shown in 1967 at the Galleria Enzo Sperone in Milan.

Dennis Freedman’s New York City living room features (from left) a floor lamp by Pucci de Rossi (1990s), a 1992 Acid Bauhaus chair by Guerriero Alessandro, Alex Da Corte’s photograph True Life (2013), and Alessandro Mendini’s Monumento da Casa (1974). A Ziggurat table lamp by Fabrizio Cocchia sits atop a Quaderna 2600 table by Superstudio, both from 1970. Photo: Stefan Ruiz. Courtesy of Dennis Freedman.

What is the most valuable work of art that you own?

To be honest, I don’t know. I’ve never had a significant amount of money and have built my collection by developing early relationships with artists and designers. The whole obsession with how much an artwork or a piece of furniture costs or realizes at auction isn’t of much interest to me. I have found that many of the very best museum quality pieces were the least expensive at the time I purchased them. Connoisseurship and vision count much more than money.

In Freedman’s study sit a 1969 Gae Aulenti yellow table lamp, a 1969 fiberglass coffee table by Studio Tetrarch, and a miniature blue model for Gianni Pettena’s 1967 Rumble sofa. Photo: Stefan Ruiz. Courtesy of Dennis Freedman.

Where do you buy art most frequently?

I frequently find rare pieces at some of the less obvious auction houses—places like Dorotheum in Vienna, Bukowskis in Stockholm, and Aste Boetto in Genoa. I also go to certain dealers like Yves Gastou, Robert Murphy (RCM Galerie), and Marc-Antoine Patissier in Paris.

What work do you have hanging above your sofa?

Over my sofa in New York City is a 7-channel video by Tabor Robak, called Xenix. I was happy to see that MoMA acquired one for its collection. It’s a brilliant and complex piece.

Joris Laarman, Bone Chair (2006). Photo: Joe Kramm. Courtesy R & Company.

What is the most impractical work of art you own?

I think, perhaps, the prototype Up 7 by Gaetano Pesce qualifies. It is quite a large, non-functional object made of unstable foam. Bits of it have fallen off. However, since it has always resembled a piece from antiquity, its deteriorated condition only adds to its beauty. It is the only piece that could not travel from the exhibition of my Italian Radical design collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston to the Yale Architecture Gallery, because the curators were concerned it would not come back in one piece.

In Freedman’s East Hampton home, Gaetano Pesce’s foot sculpture rests behind a 19th-century Austrian daybed and cast-bronze Crab and Lobster chairs (2003) by Bronislaw Krzysztof. In the background (left) sits Alex Da Corte and Borna Sammak’s As Is Wet Hoagie sculpture (2013) and on the right a 1980s floor lamp by Alessandro Mendini for Studio Alchimia.

What work do you wish you had bought when you had the chance?

When I was a student at Parsons in New York, I saw that one of Thomas Struth’s great photographs from his “Museum Photographs” series, Louvre 4, Paris, was being sold at Sotheby’s New York. It captures a woman in a royal blue coat, standing in front of Gericault’s masterpiece The Raft of the Medusa. I think it had an estimate of about $30,000. I thought I could take all my savings and scrape together enough to buy it. In the end, I was too cautious, though. But it taught me a lesson: to trust my instincts. Sometimes, it’s necessary to take big risks.

If you could steal one work of art without getting caught, what would it be?

I never steal.