Art World

What Will the $500 Million Shed Arts Center Actually Do? No One Seems to Know

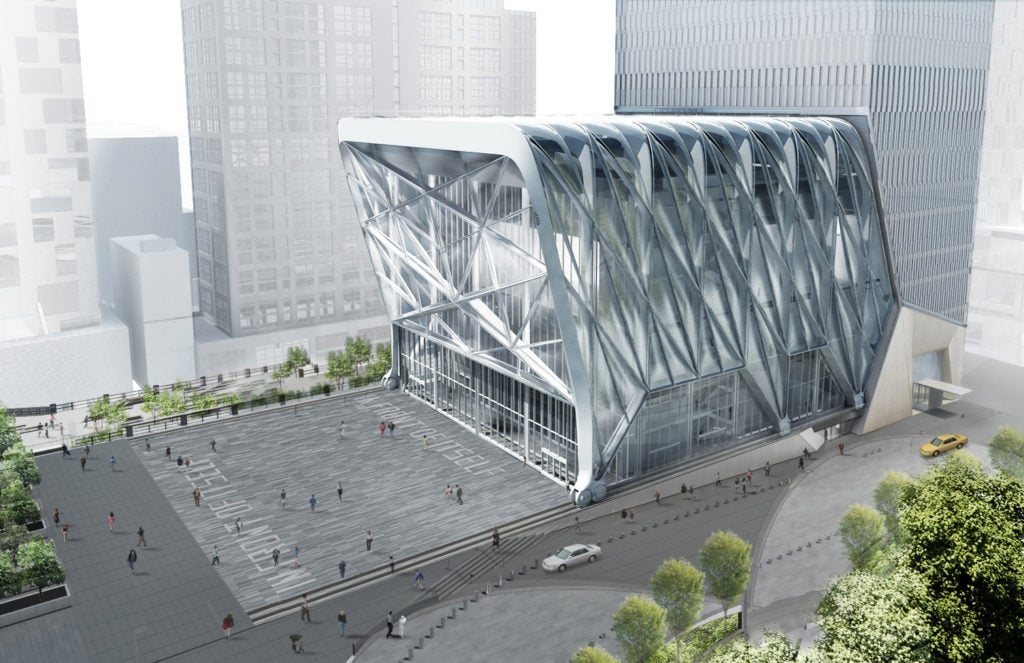

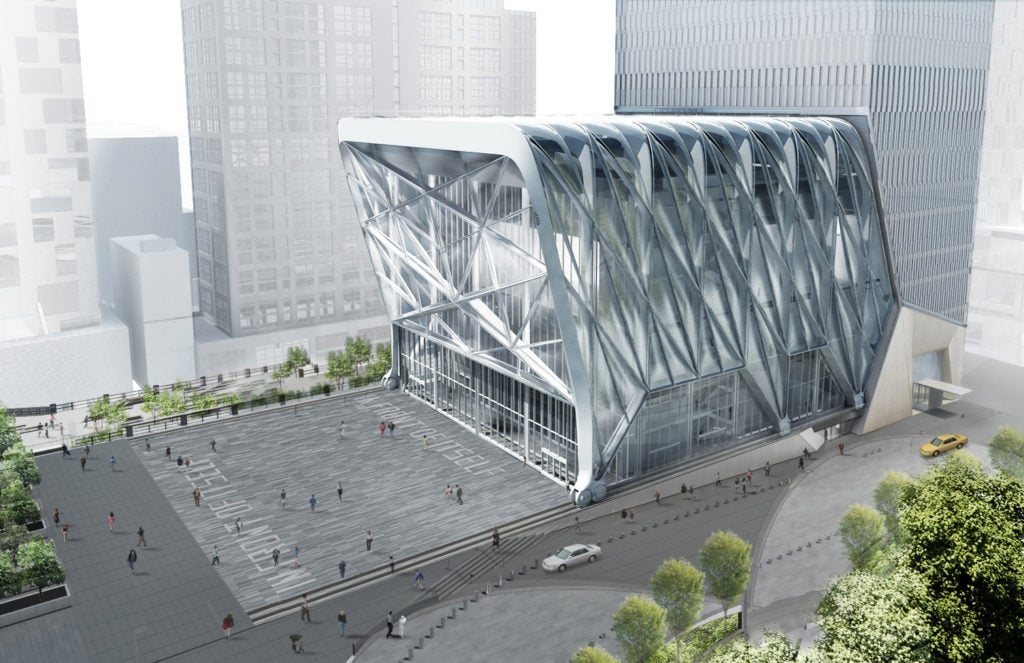

Is this the museum of the future?

Is this the museum of the future?

Eileen Kinsella

Dozens of art and architecture journalists descended on a construction site on Manhattan’s far west side yesterday—in the middle of the chaotic building frenzy that is NYC’s Hudson Yards—for a first glimpse of an ambitious and costly new addition to the city’s arts and culture scene.

The Shed, formerly known as Culture Shed and currently slated to open in Spring 2019, is described as “a multi-arts center designed to commission, produce, and present all types of performing arts, visual arts, and popular culture.” It consists of an eight-level “base building” that has two levels of gallery space, a versatile theater, a rehearsal space, a creative lab for artists, and a sky-lit event space. There is also a mobile steel outer shell that can roll out over a sprawling plaza making it a flexible indoor/outdoor event space.

The Shed, under construction, May 2017. Photo by Timothy Schenck. Image courtesy of Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Rockwell Group.

Among key news announced yesterday, by chairman of the board Dan Doctoroff, was a $75 million donation by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, (which brings the total funds raised so far, to $421 million of the projected $500 million budget) and details about the first visual art commission, a large-scale, site-specific work by Lawrence Weiner. Fabricated with custom paving stones embedded in the building plaza, the 20,000-square-foot work by Weiner is titled IN FRONT OF ITSELF and features the title phrase in 12-foot-high letters. The Shed’s chief science and technology officer Kevin Slavin has also begun collaborative projects at the MIT Media Lab, where he is a research affiliate.

So what exactly is The Shed?

If the answers are not entirely forthcoming, that may be because, two years away from its opening, organizers are admittedly unsure of the programming themselves, emphasizing instead how open-ended and fluid their approach is.

Given that there are echoes of MoMA’s unrealized “Art Bay” which called for a retractable glass wall and spaces for presentations that would be visible from the street, perhaps it is no coincidence that the same architecture firm is the lead on the current project.

The steel frame of The Shed as seen from the interior. Photo Eileen Kinsella

Elizabeth Diller, a founding partner of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, spoke at yesterday’s press conference before leading a tour, noting that such events typically center on a ribbon-cutting or groundbreaking: “You’re actually here at an unusual time when we pry open the construction fence in the middle of construction,” she told the crowd.

Diller, who has been working on the project since 2008, said: “The opportunity for us to design a ground-up building for the arts forced us to ask the question: ‘What will art look like in 10 years? 20 years? 30 years?’ And the answer was that we simply could not know. Artists today are working across disciplines, in all media and all sizes. That will continue to change. The one thing that we could always be certain of is that there would always be a need for space, a need for structural loading capacity, and a need for electrical power.”

The Shed, interior view (rendering). Image courtesy of Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Rockwell Group.

Aside from the fact that the as-yet-unknown programming is obviously inextricably linked with the architecture, Diller said: “the infrastructure is purposely built for flexibility, and our reference was the Fun Palace, the 1960s unbuilt project by Cedric Price.”

Asked if he sees The Shed filling a void in New York’s already bustling institutional landscape, Alex Poots, founding artistic director and CEO, told artnet News: “There is a need for places to commission new work. It’s more challenging, on many levels, not just financial. If we don’t make new work then we become a museum culture, which is great but only half the story of culture. We need to look to the past to learn but we also need to imagine the future.”

One of the large wheels that moves The Shed.

Poots was founding director of the Manchester International Festival from 2005 to 2015, before moving to the Park Avenue Armory in 2012 when he was appointed artistic director. “The thing for me—which is why I moved—whereas in Manchester I had this moment to do it for two weeks every two years, here we have a building all year round dedicated to that. The big shift for me is from this festival format into a year-round commission format.”

At the end of a tour through the building site, Poots emphasized that there are “no boundaries.”

Diller added: “It’s an experiment. Alex is starting to think about the first programming but at the same time, we talked about cuisine and fashion and all different kinds of things. The great thing about Alex is that he’s not a thinker [in] just one direction. He’s going to make some magic out of this.”