Art World

Why Everyone Should Be Paying Close Attention to the Case of Jailed Bangladeshi Photographer Shahidul Alam

The photographer has a stunning record as an artist and organizer. Artists across the world are taking up his cause.

The photographer has a stunning record as an artist and organizer. Artists across the world are taking up his cause.

Ben Davis

If you haven’t yet heard about the case of the jailed Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam—start paying attention.

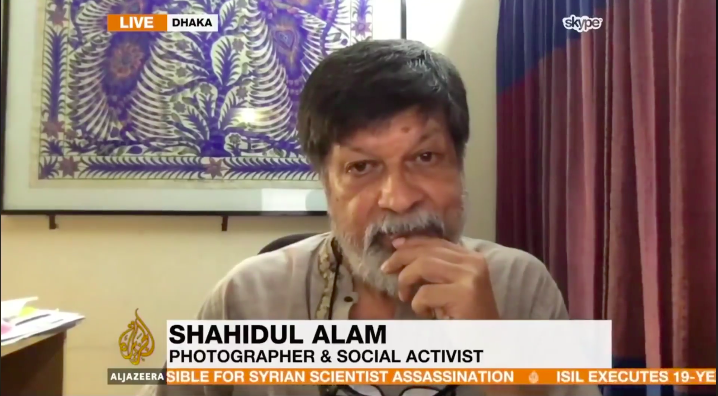

On August 5, Alam went on Al Jazeera as part of a segment explaining recent mass protests by students against traffic deaths that had shaken his country’s capital, Dhaka. Alam, a noted artist as well as a social critic, used the televised platform as an opportunity to place the protests in the wider context of Bangladeshi society, and frustrations with the ruling party.

“The looting of banks, the gagging of the media… the extra-judicial killings, the disappearances, the need to give protection money at all levels, bribery at all levels, corruption in education,” he said. “It is a never-ending list.”

Hours later, the list got one item longer: Alam himself was detained by security officers. Officially, he was charged under the draconian Section 57 of the Information and Communication Technology Act, which targets anything that “prejudices the image of the state or a person,” and has been used to criminalize criticism of the government. While in detention, he claimed to have been tortured.

Now, matters have taken a further dark turn, according to multiple people: After seven days of interrogation, Alam was denied bail at a hearing where he went unrepresented by a lawyer, and sent to jail.

Even supporters who feared the worst were shocked.

Renowned Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam (front third from left), 63, is seen in a hospital in Dhaka on August 8, 2018. Photo courtesy AFP/Getty Images.

“This is heartbreaking,” the artist Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, who started one of the online petitions in support of Alam, wrote to me last night on learning the news.

Expressions of solidarity with Alam have piled up from around the world. This includes a statement signed by Noam Chomsky, Eve Ensler, Naomi Klein, Vijay Preshad, and Arundhati Roy, followed by another on Saturday that united intellectuals including Joseph Stiglitz, Angela Y. Davis, Judith Butler, Binayak Sen, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

A coalition of hundreds of artists and photographers from India signed a letter demanding the release of Alam, including the distinguished artists Dayanita Singh, Bharti Kher, and Vivan Sundaram and the art critic and curator Geeta Kapur, among others.

Screenshot of Shahdul Alam’s interview with Al Jazeera.

Over the weekend, a coalition of Mexican luminaries spoke out as well, with signatures from Children of Men director Alfonso Cuarón, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, photographer Graciela Iturbide, and many more besides.

Alam, I think, would be the first to tell his supporters not to focus on just him: His arrest is only the most high-profile of a wave of frightening detentions and vigilante violence. That the ruling government was spiraling in an ever-more-autocratic direction was, in fact, the substance of what Alam said on Al Jazeera that got him in trouble in the first place.

Indeed, matters have degenerated within Bangladesh to such an extent that even people merely expressing support for Alam by sharing links on social media are reportedly being targeted.

While it may not be unique, Alam’s case is important. His status as a symbol of independent-mindedness and social criticism means that his prosecution stands as a message that no one is immune. “If Shahidul Alam is in jail in Bangladesh, the reality is that NO ONE has a voice in Bangladesh,” Annu Palakunnathu Matthew wrote me this morning.

As for the reaction from abroad, I cannot help but think that there would be a much larger outcry still if a broader public knew the scale of what he represents. So here is a primer on Alam.

As an artist, writer, and organizer, Shahidul Alam is responsible for a staggering array of accomplishments, within Bangladesh and beyond.

Among other things, he is not just the founder of the Drik Picture Library photo agency and its associated gallery, but of Chobi Mela, the country’s first photo festival, and an influential photography school, the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, which has trained hundreds of photographers.

#FreeShahadul graphic from the official Facebook solidarity page.

“The reason Bangladesh has a disproportionate number of world-class photographers is because of him,” the head of VII Foundation told the New York Times last week. “He’s basically a one-man kind of aid agency, journalist, media trainer, school operator, and he’s funded it all himself.”

Alam tells his own story in “With Photography as My Guide,” an essay published in World Literature Today in 2013. There he speaks about studying and working in London in the 1970s, finding his voice shooting portraits of children and winning prizes from local camera clubs. “The awards fed the ego, and the money filled my pocket, but the soul still yearned for the photographs I wanted to take—the ones that would make a difference, would make people care about issues that mattered,” he wrote.

And this is exactly what he did when he returned to Bangladesh, finding himself in the streets documenting protests against the autocrat Hussain Mohammad Ershad: “No commissions, no deadlines, no budgets, just raw passion and as much freedom as the military would allow me.” It was as a protester citizen-documentarian that Alam found his voice as an artist:

My photography was changing, too. The need for making pretty pictures for the sake of making them had gone. Freed of the commercial need for making things look good, I began showing things as they were—capturing uncertainties, fleeting movements, relationships of power and love. The storyteller in me began to surface. The camera was merely a step along the path.

Alam brought his sharp eye and sense of empathy to the politics of the image. In 1991, when a deadly cyclone left more than 140,000 dead and millions homeless in Bangladesh, he documented the disaster. But even in a moment of crisis, he challenged the hunger of the global press for ‘disaster porn,’ and the White Man’s Burden narrative that it often reinforced. He wrote:

The New York Times was a big customer: prestige, plus dollar payments. But we insisted that the pictures they had asked for were not telling the story as it was. We provided alternatives, and I remember our collective satisfaction when the Sunday review of the New York Times had a story by us across its entire back page. There were pictures of people rebuilding their boats, farmers planting seeds, medical workers providing care. It was the only story on the cyclone we’d come across that didn’t dwell on bodies, that showed strength rather than evoking pity.

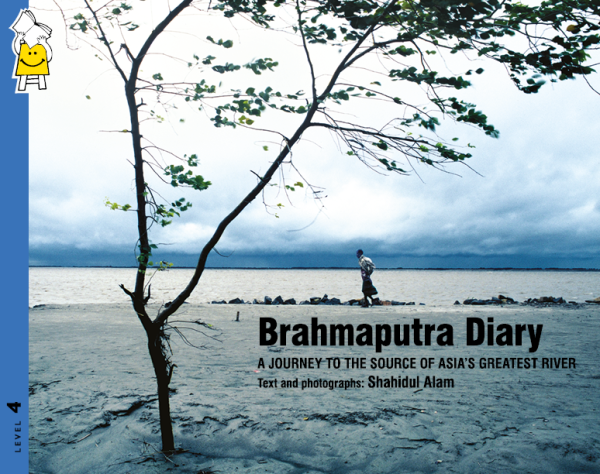

Alam has moved back and forth from political documentary to more lyrical work. One of his most important series, “Brahmaputra Diary,” documents his 1999 trip along the vast course of the Brahmaputra River, and the quiet drama of changing life along its banks. The lovely photos have been published widely, from National Geographic, to the form of a children’s book put out in 2016.

Cover of Brahmaputra Diary: A Journey To The Source of Asia’s Greatest River. (Pratham Books, 2016)

A more recent and celebrated body of work, however, is uncompromisingly confrontational. Dubbed “Crossfire,” the series merged Alam’s substantial powers as a documentarian with the tools of photoconceptualism to intervene in a contemporary debate: the so-called “Crossfire” killings perpetrated by the government’s Rapid Action Battalion (RAB).

These cases of extrajudicial killings and kidnappings of suspected criminals in the country’s drug war, sometimes compared to Rodrigo Duterte’s ultra-violent law-and-order campaign in the Philippines, have triggered national and international concern. (Human Rights Watch has extensive reports on them.) They are known as “Crossfire” killings because the standard official response to questions about the unclear nature of the deaths was to claim that the victim had been killed in the “crossfire,” while battling authorities.

Alam’s stark, dramatically empty photos unite photography with investigative journalism, using research to restage the final view of various people named as having been killed by the RAB’s operations. In 2010, Alam explained to the New York Times Lens blog the motivation for the project:

The information about the killings is known. The public has it. The police have it. The government has it. And it has not made a difference. So, we have to find something to provoke people into action.

And the “Crossfire” show did provoke action—though not the kind one would have hoped for: The government shut the Drik Gallery and stationed agents outside during the run of the show, claiming that its contents “lacked official permission” and would “create anarchy.” The series, however, was widely seen, including at the 2012 Kochi-Muziris Biennale in India. (The biennial has put out a strong statement of solidarity with Alam.)

As an artist, critic, and educator, one of Shahidul Alam’s enduring preoccupations has been to amplify the disempowered, allowing them to be seen as agents and not objects. This includes his coinage of the term “Majority World” to replace the term “Third World,” a relic of the Cold War that consigns the life circumstances of most the world’s inhabitants to a lowly, tertiary status.

A protester at the rally for Shahidul Alam at National Museum, Dhaka. Image courtesy Drik.

I mention this last because, despite the international solidarity from his many admirers, I can’t help but think of how the media interest in Alam’s case thus far pales in comparison to the outpourings of attention around Ai Weiwei in China, of Pussy Riot in Russia, or even of Tania Bruguera in Cuba—all artists who have faced detention at the hands of their governments for speaking out.

And I can’t help but feel that this may be because the persecution of dissidents in China, Russia, or Cuba fits into well-worn media narratives in the United States, inherited from the Cold War. Injustice in Bangladesh does not carry the same narrative weight for a US public—because Bangladesh is just an undefined blur on the mental map.

Activist and photographer Shahidul Alam gestures as he is removed from a vehicle by policemen for an appearance in a court, in Dhaka on August 6, 2018. Photo courtesy Munir Uz Zaman/AFP/Getty Images.

So, it’s worth saying that Shahidul Alam’s case is not just important to pay attention to, but particularly important. He has been a voice for the Majority World, and what happens for him tells us a lot about the fate of artistic voices in the majority of the world.

It may yet be that Bangladesh’s authorities get more than they bargained for. It may be that, by targeting a figure who has spent his life changing the narrative around Bangladesh, within and outside the country, they have themselves changed the international narrative; that this moment marks a new level of scrutiny of the alarming state of rights in the country. I hope so.

But that is cold comfort for Alam and his supporters right now. His jailing is appalling. #FreeShahidulAlam.