Opinion

What’s Really Going On at Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island?

An analysis of all the conflicting accusations about the luxury mega-project.

An analysis of all the conflicting accusations about the luxury mega-project.

Ben Davis

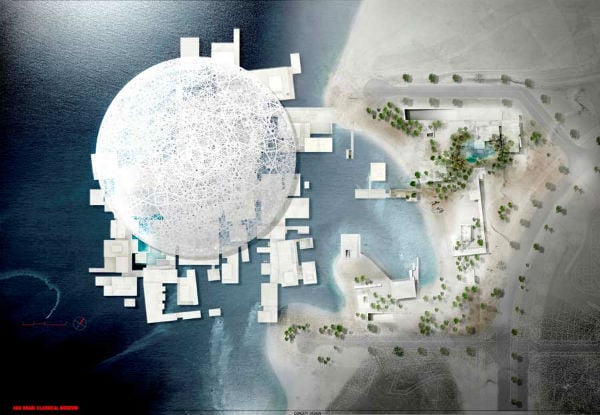

Abu Dhabi’s flashy, $27 billion Saadiyat Island cultural development continues to draw fierce international scrutiny over allegations of harsh treatment for the thousands of South Asian guest laborers imported to build outposts of international branches of the Guggenheim, the Louvre, and New York University (as well as other luxury amenities). Recent months have produced a flurry of fresh, often seemingly contradictory documents on conditions at the site:

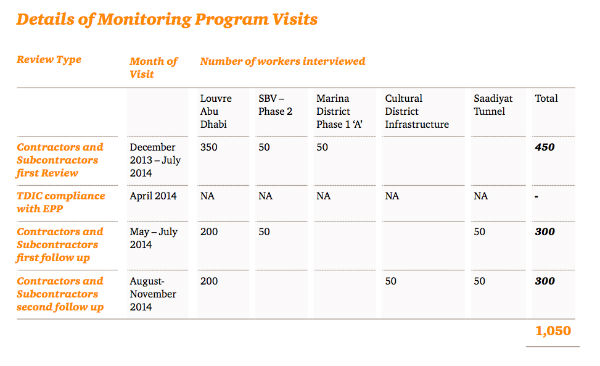

—a detailed 44-page “Compliance Monitoring Report” from PricewaterhouseCoopers (“PwC”), the international third-party monitor retained by Abu Dhabi’s Tourism Development & Investment Company (“TDIC”), based on in-person interviews with 1,050 workers, done last year;

—a scathing 89-page report from Human Rights Watch focusing on continued abuses, based on phone and in-person interviews with 119 workers, including both workers still in the UAE, and workers who had been deported;

—a response to the report by Human Rights Watch from TDIC, dismissing it for being “outdated and based on unknown methodologies” and using “anecdotal examples” as opposed to the official monitor’s more rigorous findings; and

—a public statement from Gulf Labor, a group including a variety of prominent international artists who have threatened to boycott the future museum due to the exploitation of the workers (it did its own fact-finding visit to Saadiyat Island last March), accusing TDIC and the museums involved of treating ongoing abuses as little more than a “public relations problem.”

So, what’s really going on on Saadiyat Island? Who is to be trusted? The PwC and HRC reports are dense, but combing through them in detail and comparing them actually tells us a lot about what we know—and what we still don’t know—about these questions. Here are some of the takeaways:

Observers not welcome

While HRW’s sample of workers is much more modest than PwC, it is actually impressive given the obstacles the UAE has placed in its way. “In early 2014, the UAE authorities denied a senior Human Rights Watch representative permission to enter the country and permanently blacklisted two other staff members as they were leaving the country,” the report explains. The blacklist, it notes dryly, is supposedly meant for people “dangerous to public security.”

International pressure has an effect

Still, it may be important to note that the protests, boycott threats, and journalistic exposés about Abu Dhabi’s labor conditions have had a demonstrable effect (see Artist Sneaks Into Future Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Site to Interview Workers). For instance, since 2009, labor law reforms have made conditions less abusive, at least on paper, whereas the widespread introduction of electronic payment has made companies that fail to remunerate workers easier to track—though it has not, HRW notes, ended the practice. Gulf Labor, visiting last year, stated that it was “impressed by many aspects of the model workers’ ‘village’ on Saadiyat Island,” though it noted various serious concerns.

An example of where things stood in 2014, during the monitoring period: PwC’s report mentions an incident in April when more than 2,000 workers signed a petition protesting at their living conditions, including leaks in the bathrooms, bad food, lack of cellphone service, and lack of transportation off the island. TDIC responded by relocating the workers to other accommodations, then terminating the operator of the facilities and appointing a new one. So, serious issues remained, but the authorities were capable of responding—an improvement since scrutiny was first drawn to the site.

There’s no doubt that abuse continued last year

Despite PwC’s general emphasis on progress, its official compliance report leaves no doubt that wide-ranging labor abuses continued on Saadiyat Island in 2014: “[T]he issues around recruitment and relocation fees, provision of offer letters, living conditions and payment of wages are still prevalent despite a number of initiatives being implemented.”

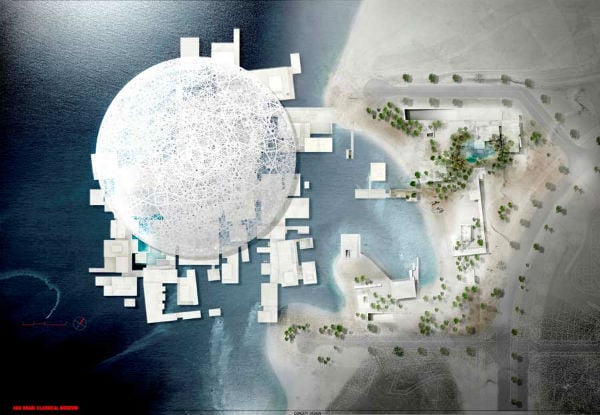

Interviewees from Human Rights Watch’s “Migrant Workers’ Rights on Saadiyat Island in the United Arab Emirates: 2015 Progress Report”

The most prevalent issue: recruitment fees

A full 88 percent of workers told PwC that they had been recruited by a service that required a fee to bring them to work in Abu Dhabi from their home country. Such up-front fees are a major target of critics who say guest worker conditions in the UAE are akin to indentured servitude. They also happen to be forbidden under TDIC’s own new labor guidelines. An anecdote from the HRW report gives a sense of why:

Three workers from Bangladesh, working for a contractor on the New York University site on Saadiyat but living two hours’ drive away in Dubai, told Human Rights Watch in January 2014 that they were on a basic salary of $190 per month—half of what recruitment agents in Bangladesh promised them—and that the company did not give them promised annual pay increases. They said they had paid approximately $2570 in recruitment fees and that, while they were unhappy with their pay and working hours and had complained to their employers, they could not go home until they had repaid their debts.

All talk, no action?

TDIC put in place a variety of new work monitoring procedures. However, even PwC concedes that as of April 2014—at the same time that work on Jean Nouvel’s spectacular new Louvre building was under way (see 300 French artworks for Louvre Abu Dhabi)—these appear to have been almost entirely for show: Reports on labor abuses were “not being escalated to TDIC management and were not acted on or used for Contractor financial penalty determination,” while “no analysis” was carried out on data submitted by various contractors working on the projects to see whether it was accurate. The authorities collected paper, in other words, and did nothing with it.

But, PwC says, TDIC has promised to do better this year.

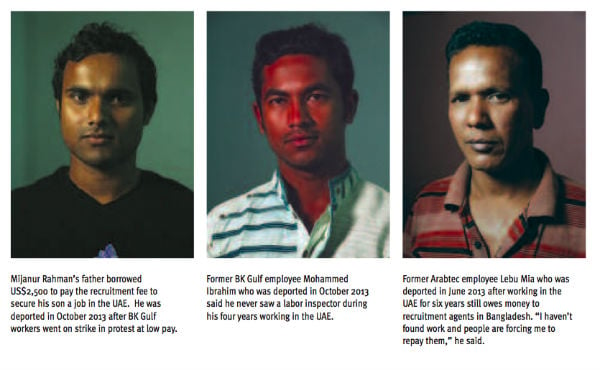

The “Implementation Framework” for TDIC’s “Employment Practices Policy,” from Pricewaterhouse Cooper’s “Employment Practices Policy (EPP) Compliance Monitoring Report,” 2014

Vague penalties

While PwC enthusiastically notes various pledges by TDIC to sanction offending companies financially, Human Rights Watch was unable to track down concrete figures on what this has meant in practice. This general opacity, the watchdog notes, is part of what leaves the system open to abuse:

In the absence of complete information on the sanctions that TDIC has imposed on contractors, examples of violations that constitute a material breach of contract, and information on what steps TDIC is empowered to take in the event of a material breach, it is hard to see how the penalty policy could have any significant deterrent effect. This is true even for serious abuses. Where protections for workers’ rights historically have been weak or non-existent, as in the UAE, migrant workers are highly vulnerable to forced labor.

Strike fallout becomes “personal incident?”

Much of the most gripping testimony in HRW’s report relates to workers deported to Bangladesh during a bitter 2013 strike that brought large-scale reprisals from police and bosses. This was followed by violent clashes between workers as Pakistanis were brought in to replace deported Bangladeshis. For reasons unclear, PwC’s official account omits mention of the strike and simply says: “[D]uring 2013, a widely reported incident occurred at the SAV as a result of a personal dispute between two individuals. This subsequently escalated into a large ethnic conflict.” By contrast, multiple Guardian reports connect the ethnic conflict directly to the fallout from the strike.

HRW all but accuses NYU’s monitor of conflict of interest

“The abuses and difficulties obtaining remedies workers described are more serious than those that compliance monitors Mott McDonald and PwC have reported,” HRW says in a summary of their findings. But while HRW appears to at least respect the findings and methodology of PwC, the watchdog is much more suspicious of Mott MacDonald, which serves as third-party monitor for the NYU campus project. It points out that back in 2006, Mott MacDonald was also hired to oversee water and electricity systems on Saadiyat Island.

Are PwC’s findings truly representative?

Much is made about the large sample size of PwC’s report as a guarantee of accuracy (14.4 percent of the “total average monthly number of workers”). However, HRW finds a hole in the report big enough to drive a cement mixer through: It only looked at workers with Saadiyat Island’s largest employers (specifically, four of the seven largest contractors and six of the 46 largest subcontractors). It is entirely possible that the experience of workers at large companies is distinct from that of those at smaller firms. In fact, some of the more distressing cases documented by Human Rights Watch involve “workers employed by a myriad of small locally owned subcontractors.”

Chart detailing Pricewaterhouse Cooper’s 2014 Monitoring Program Visits

We just don’t know how dangerous the work is

According to PwC, reports of dangerous workplace incidents on Saadiyat Island are low by world standards. In fact, they are unbelievably low. Noting this, PwC states, “This suggests that further work is required to improve the reliability of this reporting by Contractors”—an awfully subtle way of saying, “This cannot be true.” So subtle, in fact, that upon the release of the report, media including the UAE’s English-language paper the National touted the passage as evidence of TDIC’s progress rather than as evidence of progress that still needs to be made.

Demanding more

The construction of the new Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is still to come. But these reports, and others before them, offer ample record of what has happened already.

Despite a public “statement of labor values,” the NYU campus was constructed under disgraceful labor conditions, vividly documented last year by a New York Times exposé. The Louvre remains under construction, but the current Human Rights Watch report offers testimony with Nepalese workers who helped do concrete work for the contractor Robodh last year, but say they went for five months stranded in the UAE without pay—to the point where they had difficulty feeding themselves.

Given such a record, what should TDIC’s “museum partners” do going forward? Here’s Human Rights Watch’s Sarah Leah Whitson:

“NYU, the Louvre, and the Guggenheim should surely understand by now that they can’t blindly accept the UAE authorities’ assurances that workers’ rights are being respected. They need to exert their influence much more forcefully and demand much more in return for their presence on Saadiyat Island.”

And Gulf Labor:

“The Guggenheim continues to hide behind claims that construction has not begun, even as its own website celebrates its expanding Abu Dhabi collection, as showcased in the ongoing exhibition Seeing Through Light. Gulf Labor suggests that the Guggenheim should start seeing the light of workers’ welfare, instead of through it.”