Art & Exhibitions

The 2022 Whitney Biennial at a Glance: Here Are 3 Charts That Break Down What to Expect From the Anticipated Survey

"Quiet As It's Kept" is both older and more international than recent editions of the event.

"Quiet As It's Kept" is both older and more international than recent editions of the event.

Artnet News

When the Whitney Biennial was founded in 1932, it was conceived as a bellwether survey of U.S. art from the preceding two years. That’s still loosely the idea driving the museum’s signature show, even if its mission has gotten much more fluid over the ensuing 90 years.

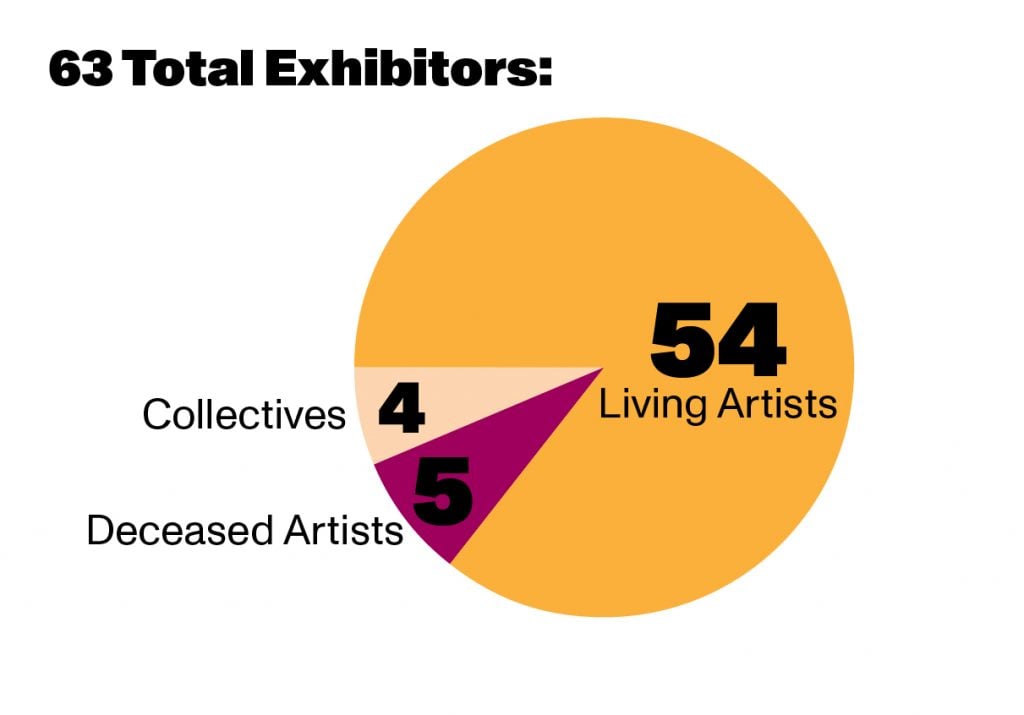

The newest iteration of the biennial, “Quiet as It’s Kept,” is proof of this broadening. It will bring together 63 artists and collectives whose work spans generations, mediums, and—perhaps most notably—geographic borders.

For curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, organizing a show with the aim of drawing conclusions about the state of art today would be an irresponsible exercise at the best of times. But in 2022—after a pandemic, a presidential election, and a spate of global protests—generalizations are simply unthinkable. Instead, the 80th Whitney Biennial reflects the precarity of our moment.

“Rather than proposing a unified theme, we pursue a series of hunches throughout the exhibition,” the curators explained earlier this year upon announcing the show. Among those “hunches” are “that personal narratives sifted through political, literary, and pop cultures can address larger social frameworks” and “that artworks can complicate what ‘American’ means by addressing the country’s physical and psychological boundaries.”

© Artnet News

For the last biennial in 2019, Artnet News surveyed recent examples of the Whitney’s show to identify patterns among participants. With a new entry onto the list, we have a new set of observations.

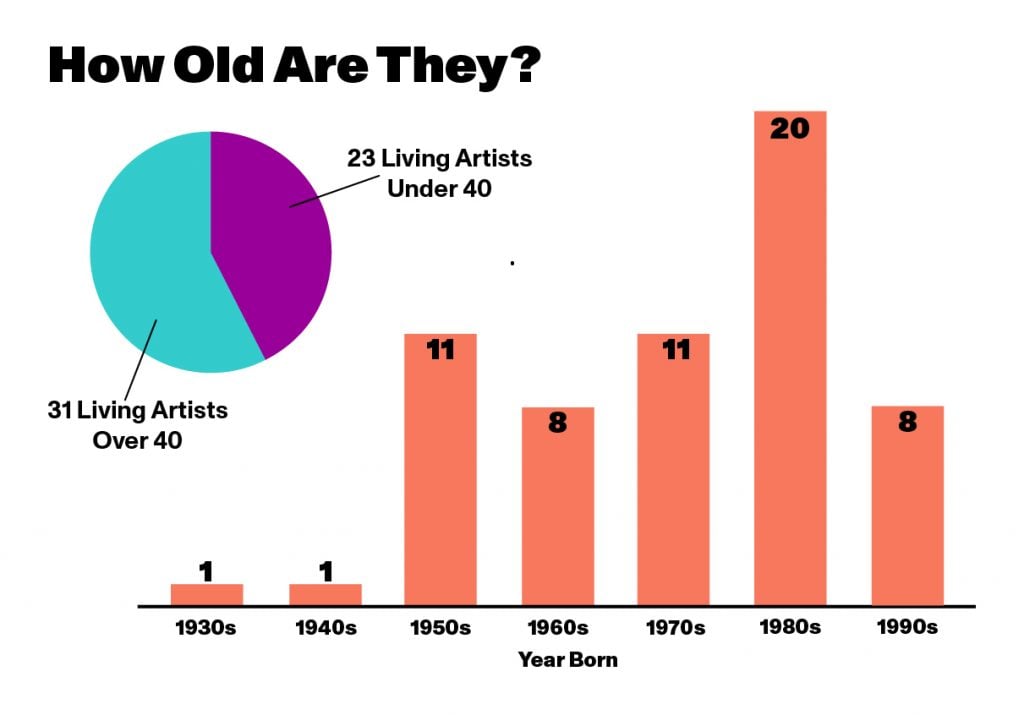

For one, this year’s participants are a little older, on average, than those of previous years. Of the 2022 artists, 31 are under 40, while 23 fall on the other side of that line.

Puerto Rican choreographer Awilda Sterling-Duprey, born in 1947, is the oldest of the bunch. The youngest is Mexican video artist Andrew Roberts, born in 1995. Five artists (Steve Cannon, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha N. H. Pritchard, Jason Rhoades, and Denyse Thomasos) are deceased—an uncommonly high figure for an exhibition so ostensibly tethered to the present.

© Artnet News

Visitors will almost certainly discover at least some new names at the exhibition next month, if not many. Refreshingly, you’ll find just seven of the biennial’s artists on the rosters of the country’s four biggest galleries (that is, David Zwirner, Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, and Pace Gallery).

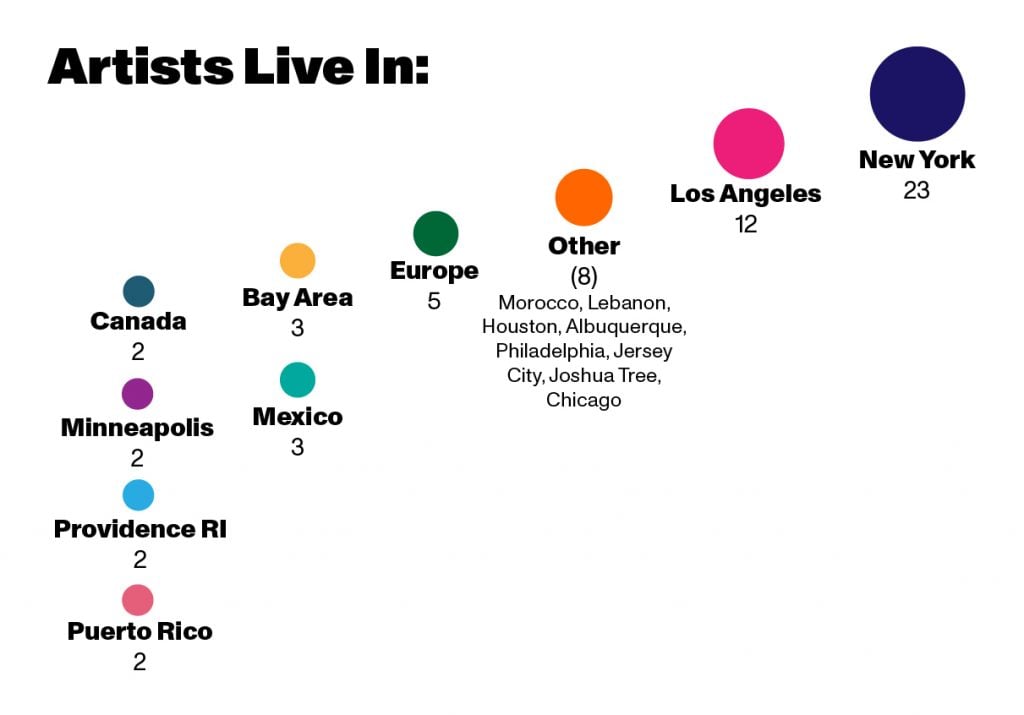

The vast majority of participants do, however, hail from coastal hubs. Twenty-three, or 36 percent of the bunch, live and work in New York (or at least divide their time between there and another city); 12, or 19 percent, call Los Angeles home. (For comparison, in 2019, 51 percent of participants came from New York, and 11 came from L.A.)

© Artnet News

The 2022 biennial also skews more international than other recent editions.

Sixteen artists, including Yto Barrada, Alfredo Jaar, and Duane Linklater, were born outside of the U.S. That accounts for a solid quarter of the participant list, a high mark last seen with the 2008 biennial, in which more than a quarter of artists were foreign-born. That percentage decreased for each of the successive biennials, dipping to 17 percent in 2019.

Eleven of this edition’s artists live and work abroad, including three in Mexico (Mónica Arreola, Alejandro “Luperca” Morales, and Roberts) and two from Canada (Rebecca Belmore and Duane Linklater).

“We wanted to make an exhibition that looks like what America really looks like,” Breslin told Artnet News in an interview, “which is a country of immigrants, a country of pressure along the border.”