I went to the 2019 Whitney Biennial with a brief to consider the photography in the exhibition and left thinking about the power of affiliation. The curators have said they thought a lot about who is an American, and put together a biennial that maps more closely the nation’s shifting demographics than previous editions. A new mainstream is being forged in America, and if you had any doubt about what it might look like, this is it. In short, this is photography by the new majority.

The photography and video here made me consider the politics of belonging, and if, or how, we are all going to live together. The work refers to the ties that bind—groups of friends, “the art world,” the “human family”—but collectively, it made me think about integration and opportunity, and the conditions and compromises exacted upon membership at a time when it has become difficult to imagine life outside of institutions. How do networks circumscribe or provide opportunity? Who belongs, and to which communities?

For its part, the Whitney has carefully crafted an invitation that signals contrition, stability, and inclusion. The artists can be said to come from nearly every conceivable historically marginalized group. Co-curator Rujeko Hockley appears to be the biennial’s first black curator since Valerie Cassel Oliver co-organized the show in 2000.

Although the photographs and video have been made by minorities of all kinds (racial, gender, sexual, religious), it is not the work of outsiders; in fact, some have been celebrated in the “mainstream” art world in recent years. A number of the photographers have published acclaimed monographs (Curran Hatleberg’s Lost Coast, John Edmonds’s Higher, Paul Sepuya’s Studio Work) or have been featured in past iterations of MoMA’s “New Photography” (Sepuya in 2018; Lucas Blalock in 2015). They are the recipients of prizes, shoot editorial campaigns, and have their work collected by major museums. Some have even inspired their own imitators.

We might learn something from this roster about who has access to an education in photography nowadays, or at least, who has access to Yale. From the perspective of someone who works to expand access to photography among people without such accreditation, it was sad but not surprising to note how the same networks prevail.

The work sometimes feels like a product of these institutions, and is framed in relation to recent trends and jargon. Though the organizers would have you believe this is a show about identity, the texts addressing the photographs refer mostly to the body, visual culture, and photography itself. I wondered if using language in a way that minimizes identity was a survival tactic artists might have developed for broader respect and recognition within these systems. Though the photographs are made by artists who are queer, gender nonconforming, Asian, Latinx, or black, almost none of them discuss these cultures directly in their work. Looking back, I’ve also wondered if, in some ways, this is actually a post-identity show that has managed to be framed around identity politics simply based on who was included.

Many of the parties seem perfectly comfortable taking up space in the American art world, and many appear unbothered by the idea of compromise. There are whiffs, too, of the youthful expectation of being seen and counted (this is a very young show), and of the comfort in putting it all out there.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, I Prayed to the Wrong God (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

When I saw Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s sizable projections detailing Afro-Atlantic ritual practice, a departure in technique from often-coded work on this subject, I sensed the rules are changing about what we black people show in public, and to whom. Maybe it’s this sense of belonging that has inspired critics to call the show tame. But these aren’t reactionary positions; this is what the new normal looks like.

The curators admit the work feels less “angry,” and they have framed the show’s politics in very broad terms. If the politics feel muted, or lack urgency, it may be because a majority typically doesn’t announce its identity so loudly. Two years ago, the biennial installation opened into conflict and clamor: Dana Schutz’s roughly abstracted Elevator, Occupy Museum’s jagged, wall-length Debtfair, Jon Kessler’s whirring Evolution. This 2019 show, by contrast, eases you in with a gentle invitation. The show strikes me as very quiet, a potential effect of hanging work in an endless warren of galleries that feel beyond human scale. The volume of the videos is soft. The overall effect is relative calm. This is politics on Xanax.

Looking at the Biennial

Elle Peréz’s portraits build in intensity as you wander across the room. There are scars, some self-inflicted, others incidental, yet the photographs convey great tenderness. The first three photographs read as intimate portraits of friends and reveal trust and esteem between Peréz (who uses they/them pronouns) and their subjects.

Elle Pérez, Jose tattoo, Sable, and Jane (all 2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The six Peréz photos on an adjacent wall differ pointedly in style and approach from one another. In a color photograph, Mae (three days after), a very young woman with surgical scars peers downward through bruised, puffy eyes, gaze inexplicable. In a black-and-white photograph, a hand holds a vial of testosterone, calling to mind of the photography of early scientific discovery. As a group, it’s a far friendlier selection than those in Perez’s solo show at PS1, “Diablo” (2018).

Installation view of works by Elle Pérez in the Whitney Biennial. Image: Ben Davis.

Though we can surmise some of the photographs refer to stages of gender confirmation surgery, the caption refers only to “the experience of pushing the body.” This was the first example I saw of an elision of direct claims to “identity politics” in favor of broader art-speak. Either way, Perez’s focus on the body and pain is a useful counterpoint to the sunny depictions of queerness that have permeated the larger culture.

Installation view of works from Heji Shin’s “Baby” series. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Heji Shin’s “Baby” series is a very different take on pushing the body. Shin has photographed babies’ heads as they emerge from their mothers’ haunches, purple, misshapen, and dripping blood. It seems a deliberately stark contrast to the emerging visual cultures surrounding motherhood, nursing, and birth. Unlike, for instance, Carmen Winant’s collages of women during labor, or the idyllic images of affluent motherhood that infest Instagram, Shin’s work is centered on the child. In some ways this makes the experience of childbirth more relatable. It’s rough business being born, and all of us have been there.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Ariel Goldberg, Camera Lesson (_2210485) (2018) Ariel Goldberg, Camera Lesson (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Paul Sepuya continues his work inviting friends and collaborators into his studio to reflect upon the nature of photography itself (full disclosure: I know Sepuya). This body of work more clearly questions authorship and the relationships between subject and photographer than other recent installations by the artist in the New Museum’s “Trigger” and MoMA’s “New Photography 2018.” In a handful of images called “Camera Lessons,” Sepuya and various friends hold cameras before a mirror. In some instances, it’s hard to tell who has taken the resulting photograph. Bodies are cropped beyond recognition or otherwise abstracted, but Sepuya’s presence is always keenly felt.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya and A.L. Steiner’s Darkroom Mirror Portrait (_1000510) (2018) at the Whitney Biennial 2019. Image: Ben Davis.

In one of the most striking images, you see only Sepuya’s muscular arm, emerging from the edge of the frame to grip the top of a camera, presumably to release the shutter. Lying below the tripod is the artist A.L. Steiner, topless and smiling, hand raised to the lens, nearly meeting his. Sepuya clearly retains control, though Steiner, looking upward, joyfully submits. Ambiguous power dynamics, again, are the point.

Installation view of works by John Edmonds. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

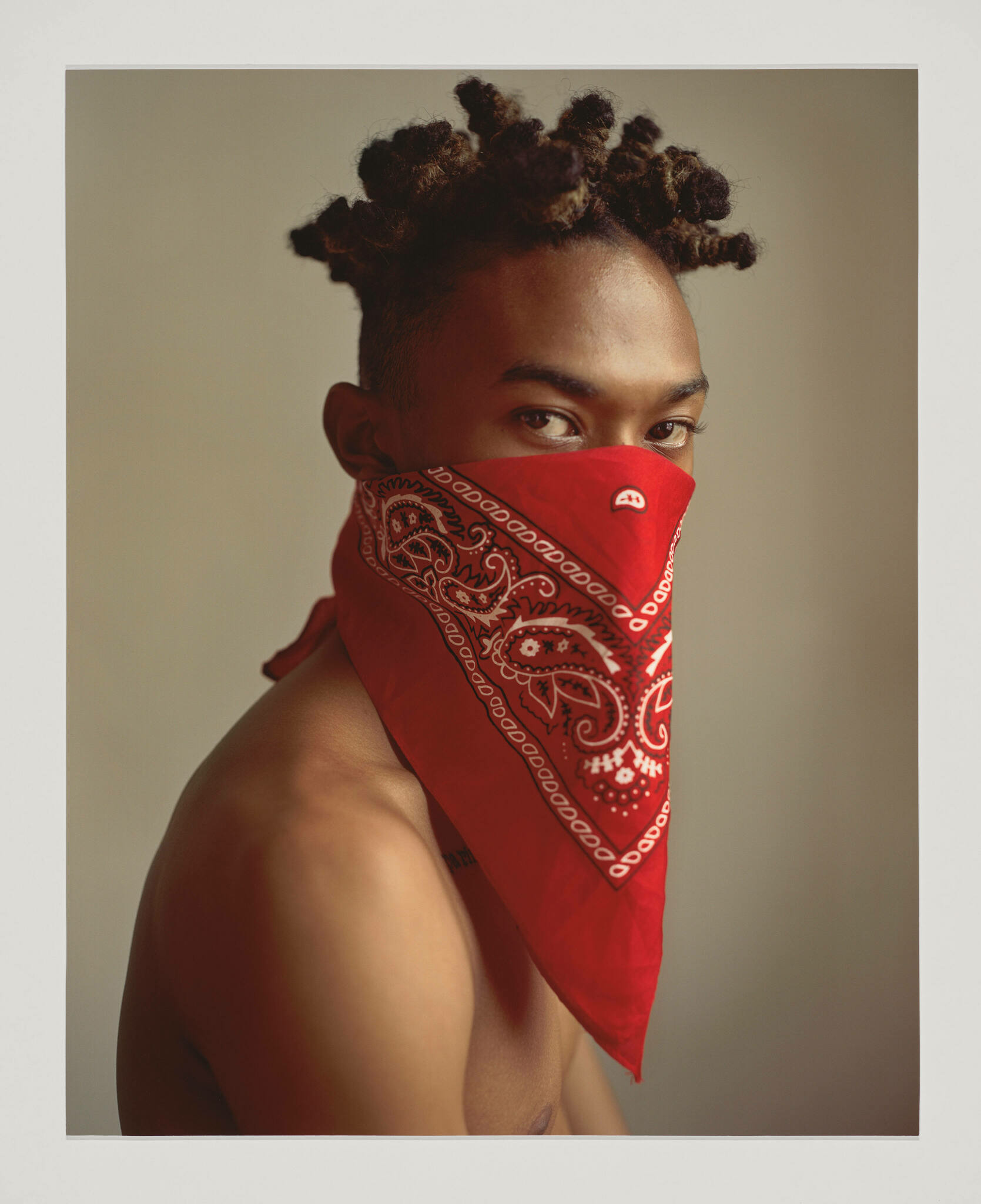

When I saw John Edmonds’s Criminal in the publicity material—a portrait of a shirtless man gazing into the camera, covered partly by red kerchief—I feared this would be an installation of photographs that claims to center black people while secretly centering white audiences and their presumed prejudices. But the installation of his photos at the Whitney retains much of the playful pleasure of Edmonds’s monograph, Higher (2018), which acknowledges how his largely black subjects are exposed to, and feel at home within, seemingly incongruous visual cultures.

Installation view of works by John Edmonds. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The images are not uniformly strong, and some suffer from imprecise studio lighting, but the codes can be read on multiple layers. Rhetorically, Edmonds is concerned with the tropes of Modernism: his young men hold West African sculptures; women pose with wooden masks, hair fingerwaved in 1990s-does-1920s style. Many of these images can also refer to the well-worn “kings and queens” narratives that have been shared in black communities for decades, and, because the statuettes are clearly knockoffs, it also turns these ideas on their head. Elsewhere, in the softly lit America, the Beautiful, three men don du-rags in the national colors of white, blue, and red, staking their unmistakable claim to American identity.

Installation view of works by Curran Hatleberg in the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Image: Ben Davis.

I am always surprised when anything resembling social documentary photography makes its way into the biennial; rarely do these worlds merge. Curran Hatleberg’s works, unfortunately annexed on the third floor, don’t quite hold my attention—I can’t tell if they should be printed much larger, like the works of Alec Soth, to whom he is sometimes compared—but they do hold the promise of something somewhat new. Despite the rough-hewn homes and concrete junkyards, Hatleberg’s pictures suggest irrepressible vitality of community and the natural environment.

Hatleberg takes up documentary’s humanistic ideals in earnest. We learn from a caption that the artist “aims to use photography to undermine bias and forge understanding across difference and distance.” I nearly blush at his startling sincerity, so completely out of step with the tribalism of recent years. In the audio guide, he elaborates, “It’s only through others that I think we’ll understand ourselves, our country, and our current moment.”

Curran Hatleberg, Untitled (Dominoes) (2016). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Although Hatleberg’s photographs were taken on several road trips across the United States, the people in them feel as though they belong to one single, multiracial community. This fictive landscape suggests a kind of political promise of coalition between economically marginalized black and white people that is yet to be fully realized—either online or in national politics.

Installation view of works by Martine Syms, including [at center] Intro to Threat Modeling (2017). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

It wasn’t until I reached the sixth floor that I saw a kind of unease with inclusion as a subject itself. In Intro to Threat Modeling, Martine Syms, whose work was the subject of a recent show at MoMA, riffs on potential adversaries and considers whether the art world, as a site of coalition-building, can really be her home. Syms’s video cites the writing of Bernice Reagon Johnson, a founder of SNCC, who warns of the discomfiting process of building across difference.

Installation view of Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

A line from another work, Ilana Harris-Babou’s video Human Design, might have summed up the self-protective, insider-outsider stance of the show best: “It really comes down to how you frame things, and what you let people see.” Members of the new majority will have to renegotiate the terms of their participation—who the work is for, in which contexts it will be seen, and who may evaluate its merit.

The Paradoxes of Inclusion

Overall, rather than critiquing the dominant culture, the work in the biennial reflects a keen desire to position one’s self within it. A number of these works are concerned with correcting or subverting photographic practices of the past, like Modernist primitivism or seated portraiture, and articulating the impact these practices have on our perceptions of self and others. The curators have said their show reflects “a rejection of the digital”; in photography, this is expressed by strategies that call to the past: Sepuya’s cameras are outmoded 35 mm and medium format models; Hatleberg’s work takes the form of a road trip, a romantic method of documentary-making in the age of the selfie; Edmonds’s shadowy lighting is a reference to Man Ray.

As a result, many of the photographs and videos feel familiar even if the subjects are new. Meriem Bennani’s compelling videos with Moroccan students who navigate French schools—another meditation on belonging—were among the few that felt unconcerned with older art historical canons.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani’s work in the Whitney Biennial 2019. Image: Ben Davis.

Elsewhere in the biennial, artists’ references to visual media more generally are notably out of time: Nicholas Galanin’s tapestry depicting a staticky tube television as a metaphor for “whiteness”; Troy Michie’s collages using pages from ‘70s-era porn magazines as a reference to sexual stereotypes; and Alexandra Bell’s prints based on the tabloid headlines of the New York Daily News from 30 years ago as a way to foreground pervasive racism. These relics of an older media order—of television, newspapers, and magazines—have made a lasting impression on the biennial’s artists even as they are becoming obsolete.

Nicholas Galanin, White Noise, American Prayer Rug (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

But aside from Bennani’s work with animation, Lucas Blalock’s experiments with Photoshop, and Martine Syms’s vertical video, most of the photography and video on view seems decidedly removed from the new reality shaped by digital tools, algorithms, and the end of mass culture, and notably oriented toward the museum’s project of historicization. The work most engaged with of-the-moment visual technology is also the most politically current: the collective Forensic Architecture’s much-commented-upon video attacking the Whitney’s own patron, Warren Kanders, for his company’s ties to state violence at the border, which details how machine vision can be used by activists.

Their methods are estimable but the effect of the video is unsatisfying. The Whitney has paid Forensic Architecture to become a watchdog, but considering the frequent use of tear gas upon civilians worldwide, which problem does that really solve, and what bearing does it have on Kanders’s association with the museum? Does inclusion of the formerly critical inherently serve to neutralize criticism? This strikes me as a central question surrounding the visual politics of the show.

Installation view of Forensic Architecture, Triple-Chaser (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

As I think of the paradox of inclusion, I can’t stop thinking of the art dealer Linda Goode Bryant’s recent remarks in the Art Newspaper about what she perceives as the failed mission of Just Above Midtown, her influential gallery that focused on creating space for black artists, which closed its doors in the 1986. Her goal, she said, was never integration, or “to be recognized and succeed in this art world.” That ship has sailed—and in fact, symbolizing the changing relation of alternative to mainstream, MoMA is planning a show about the gallery. What will it mean for artists who were formerly marginalized to be both “in it” and “of it?”

Overall, the 2019 Whitney Biennial made me wonder if we are marking the end of outsider culture in America. In recent weeks, protesters from the Bronx to East Harlem to Chelsea have demonstrated their faith in arts institutions by demanding changes of them, as opposed to developing underground practices which forgo these complicated places altogether.

Perhaps, as the historically marginalized form the new mainstream, it becomes harder or less desirable to imagine life outside of institutions. The center stage the biennial has given to photography by the new majority suggests why protesters care enough about these institutions to defend them, and why the artists can’t quite give them up.