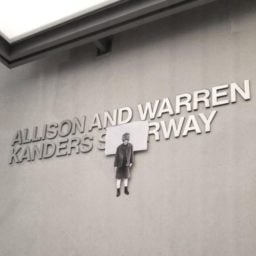

The firestorm of opposition to the continued presence of Warren B. Kanders, as vice chair, on the board of the Whitney Museum, is likely to intensify further with the opening of the 2019 Whitney Biennial. That’s because one of the biennial’s stand-out artworks, a 15-minute video titled Triple Chaser, narrated by former Talking Heads singer David Byrne, deals directly with the products made by Safariland, the company for which Kanders serves as CEO and which produces weapons for the police and military, including tear gas that has been used at the US border against migrants.

Indeed, the new artwork by London-based collective Forensic Architecture doesn’t just reflect on Sanders’s connection to the Whitney, or his business dealings. In what reads as an update of Hans Haacke’s conceptual artworks dealing with museum patronage for the age of Artificial Intelligence, Forensic Architecture has used their biennial commission to launch a functional prototype of a new application to further investigate and expose how Safariland weapons are used around the world.

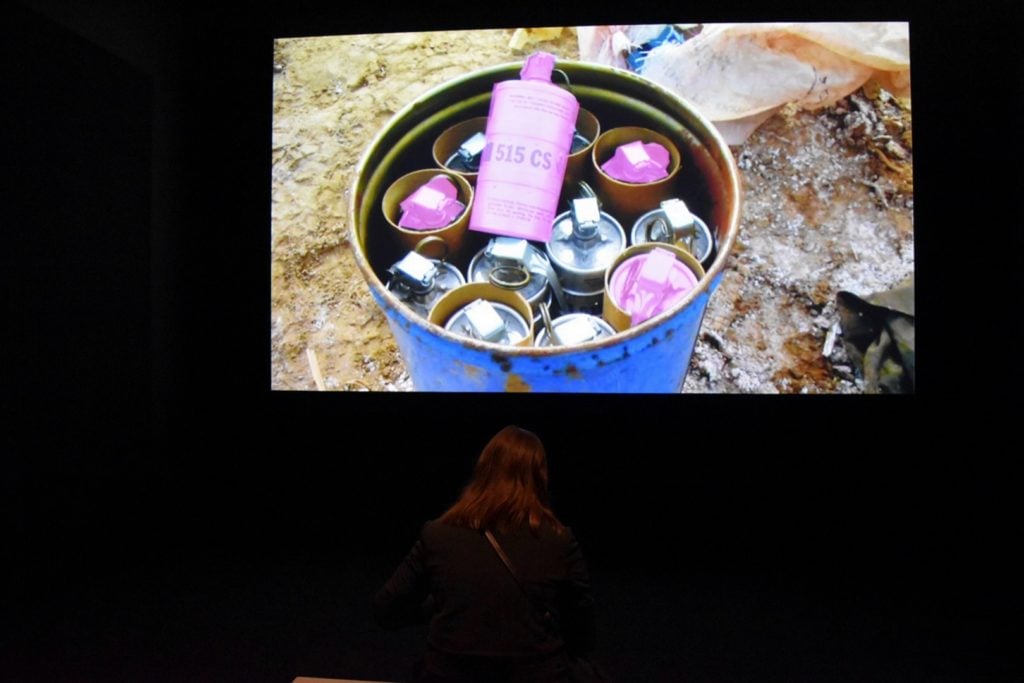

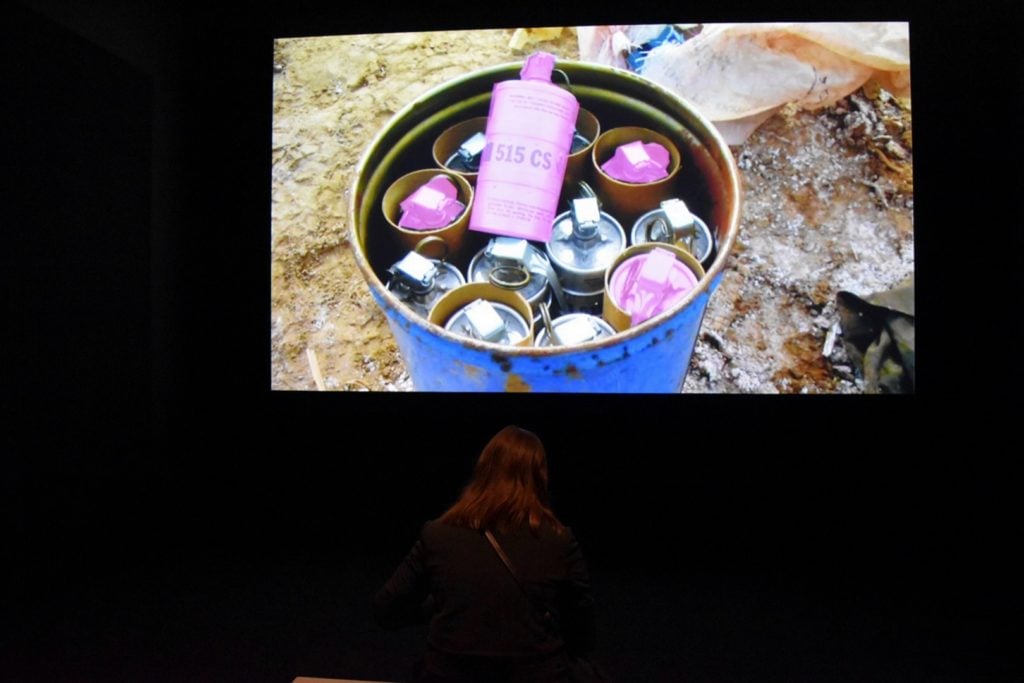

The film at the Whitney doubles as an affecting video artwork in its own right and as an explanation of how the proposed technology might work (Forensic Architecture has collaborated with documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and Praxis Films on the piece). Not surprisingly, the small screening room was packed throughout the press preview at the museum this morning.

The Story of Triple Chaser

In the wake of protests around Kanders’s patronage of the Whitney, Forensic Architecture, led by “principal investigator” Eyal Weizman, decided to respond to the controversy as part of its contribution to the 2019 Biennial. After holding talks with organizations including the Israeli human rights NGO B’Tselem and the UK-based Omega Research Foundation, the group settled on focusing their research on a Safariland-manufactured grenade known as the Triple-Chaser.

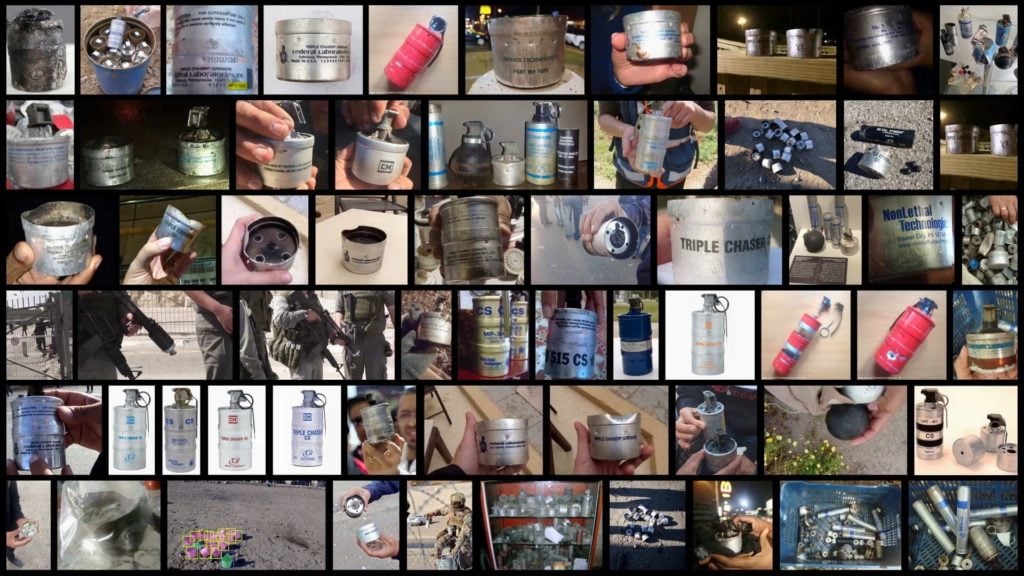

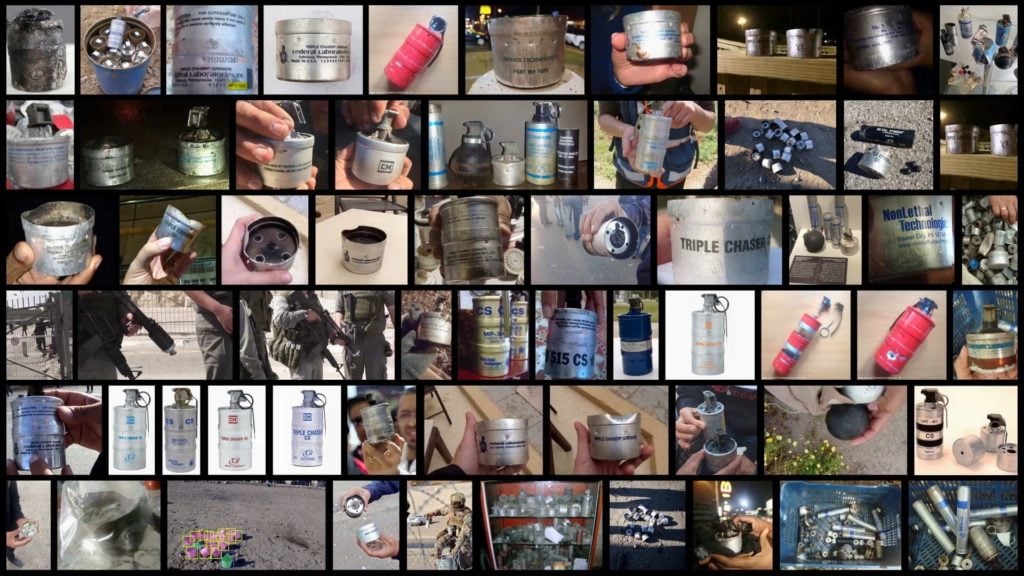

Images of the Triple-Chaser in action are relatively rare, the collective says. “Whereas the export of military equipment from the US is a matter of public record, the sale and export of tear gas is not,” Forensic Architecture’s website comments. “As a result, it is only when images of tear gas canisters appear online that monitoring organizations and the public can know where they have been sold, and who is using them.”

Still from Forensic Architecture’s Triple Chaser (2019). © FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE, 2019.

And so, for their project, Forensic Architecture has set out to use technology to speed up the process of such online investigation.

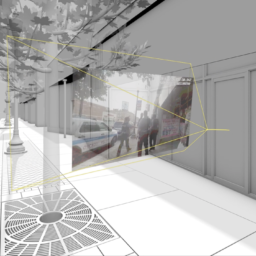

Triple Chaser looks to the branch of artificial intelligence known as computer vision, in which software is taught via large-scale repetition to recognize particular objects within larger images. Through this technology, Forensic Architecture thinks it can automate the slow, painstaking process of manually inspecting conflict photos to find evidence of Safariland’s products and their harrowing human consequences.

The scarcity of confirmed images of the canisters in action creates an inherent challenge for the use of computer vision. Without a “training set” of numerous examples depicting the target object from a comprehensive set of angles and in diverse environmental conditions, an algorithm’s attempts to recognize the target object will be wildly ineffective. (For example, no matter how many daytime images an algorithm processes, its training will likely result in nothing better than guesswork for the same object captured in nighttime or low-light images.)

To solve this problem, Triple Chaser explains, the collective “set out to create a synthetic set” of Triple-Chaser images. The group reached out to activists to find and photograph Triple-Chaser grenades. Among the images gathered, one was sent by artist Emily Jacir sent one from her art and research center in Bethlehem, while more were documented by an insurance claims adjuster in Tijuana.)

From these examples and others, as well as from the specifications listed in the product catalogue, Forensic Architecture generated a complete digital model of the Triple-Chaser, then inserted it within thousands of artificially generated, photorealistic ‘synthetic’ environments to simulate the myriad situations in which tear gas canisters are deployed and documented. This allowed their machine vision algorithm to dramatically improve its ability to detect real images of the canisters online as they appear.

“In this way, ‘fake’ images help us to search for real ones,” Forensic Architecture summarized in a statement, “so that the next time Safariland munitions are used against civilians, we’ll know.”

Forensic Architecture’s video project Triple Chaser at the Whitney Biennial. Photo by Eileen Kinsella

Uncomfortable Conversations

According to a product description, the Triple-Chaser consists of three separate canisters “pressed together with separating charges between each. When deployed, the canisters separate and land approximately 20 feet apart allowing increased area coverage in a short period of time. This grenade can be hand thrown or launched from a fired delivery system… It has an approximate burn time of 20–30 seconds.”

The film at the Biennial is split into chapters that trace the history of Safariland, as well as the effects of tear gas on the human body, and known instances when it has been used to suppress dissent, including the use of tear gas in the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Turkey. It also lays out the role that Kanders plays in Sierra Bullets, a company that produces ammunition that has been used by Israeli Defense Forces, and details the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights’s use of the Forensic Architecture’s research to put pressure on Kanders’s company.

At one point, Triple Chaser shows a letter from the ECCHR to Sierra Bullets, dated May 5, 2019. “This letter is to inform you that we are considering legal steps against you,” it begins, going on to detail how Sierra Bullets and its directors may be “aiding and abetting war crimes through the sale of their products.”

“Early on in our research we thought one of the most striking things we could do would be to present, clearly and simply, every instance we could find of Safariland’s products being used against civilians,” project coordinator Bob Trafford told artnet News via email. “We found 28… that’s 28 times that Kanders has profited from violence against civilians exercising a democratic right. We hope, dearly, that this makes for some uncomfortable conversations.”

“Complicated Questions”

In remarks to the press this morning launching the Biennial, Whitney Museum director Adam Weinberg did not mention Kanders or the specifics of the recent protests that inspired Forensic Architecture’s work directly. However, after praising curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley for looking beyond the “ever-present art market” and thanking the museums funders, Weinberg did allude to the controversy in his concluding remarks. Here they are:

In closing, I’d like to acknowledge today that the Whitney’s Biennial has a long tradition of controversy and protest.

In 1944, the Whitney Annual was widely criticized for favoring the two abstract modernist styles over more representational work. The fervor over this topic went so far that in 1950, the Whitney, MoMA, and the ICA Boston jointly published a public statement in defense of modern art.

The 1980s brought protest over the lack of female participation in the 1987 biennial, rightfully. And of course in 1993, the vastly derided Biennial… angered the public for in fact being too political. It seemed at the time that much of the public was not ready for a museum exhibition that overtly took on the urgent issues of the day: poverty, AIDS, homophobia, racism, and class lines.

Sadly, these issues all remain in the present. We continue to address them head on. But today, any line between the topics addressed by the sanctified museum and those in the real world are almost negligible. The museum is the world and the Whitney is an active participant.

We recognize that it is a great responsibility and a great privilege to give artists a platform for their ideas and voices. This is a challenging time for many of this country’s cultural and educational institutions. Here at the Whitney we are engaged daily in exploring the range of difficult topics dealing with fairness, participation, and ethics.

These complicated questions are also being debated publicly, with a range of viewpoints being expressed on all sides. We take these questions very seriously. We are listening, we are discussing, we are learning.

I’m deeply grateful to the entire staff of the Whitney Museum and board for working together to better fulfill the founding mission and the aspirations of the Whitney Museum of American Art. I am optimistic that we will meet the challenges before us, and our future will be better for it.