Art & Exhibitions

Does the New Whitney Museum Herald a Golden Age for New York Institutions?

Museum insiders are surprisingly bullish.

Museum insiders are surprisingly bullish.

Brian Boucher

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s Meatpacking District museum, opening May 1, is fiercely awaited. In its new building, designed by Renzo Piano, the galleries and sculpture gardens will nearly double the museum’s previous exhibition space, with two floors devoted to showing off its collection. The museum expects to take in spillover from the millions of yearly visitors who regularly traipse the High Line. Yet, despite having made the kinds of changes that often unleash torrents of criticism (take a look at how the public responded to the MoMA’s and the Frick’s planned expansions—see MoMA Moves Forward with Folk Art Museum Demolition and “Save the Frick” Petition Racking Up Signatures), museum insiders we spoke with are, surprisingly, unanimously bullish on the museum’s move and amplified digs.

“The only way to think is to think big,” former Museum of Modern Art curator Robert Storr told artnet News by phone from his office from Yale University School of Art, where he is the dean. “The Whitney is doing everything necessary to prepare the ground for them to land well.”

Former Whitney director David Ross, now chair of the art practice department at New York’s School of Visual Art, was not initially in favor of the move, but had a change of heart. “I recognize that they’ve made the right decision,” he said.

“The Met has turned a corner and become the institution we always hoped it would be,” Ross added, “and considering what the New Museum has become, New York is headed for a golden era.”

Ross and Storr made no secret of their dim outlook on MoMA’s expansion, and Ross added that the Guggenheim’s expansion is problematic, making their endorsement of the Whitney’s move all the more notable.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Broun, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in the nation’s capital, observed that “It’s good for a museum to completely rethink from scratch once a generation. The world changes.”

Beginnings: An Artist Patron and a Rejection

The museum got its start with a rejection, when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art declined an offered gift of paintings and sculptures from the collection of artist and impresario Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Whitney had collected Ashcan School artists such as John Sloan and Robert Henri, along with Maurice Prendergast and Stuart Davis. She also bought works by the Japanese-born artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi, foreshadowing the museum’s flexibility on what it is appropriate for a museum of American art to collect or exhibit.

When the museum opened in 1931, there were three curators, all artists, under director Juliana Force. In a phone interview, chief curator and deputy director for programs Donna De Salvo pointed out that it was Force who began a more methodical acquisitions policy, as Whitney hadn’t been collecting with an eye to forming a museum collection.

Even today, De Salvo oversees just ten full curators, though the museum’s collection has grown to some 22,000 objects. (The full curatorial staff is about two dozen.)

The institution first opened at Eight West Eight Street, now the home of the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture. It soon outgrew this home, moving to midtown and then in 1966 to its Upper East Side home, a Brutalist sculpture of a building by Hungarian-born architect and designer Marcel Breuer.

For perspective, it might be helpful to remember that that year, president Lyndon B. Johnson was ramping up the U.S. presence in Vietnam. Also in 1966, John Lennon claimed that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, and The Sound of Music won the Best Picture Oscar.

Art in America devoted a 23-page section to the museum, featuring a 15-page portfolio of artworks, selected by then-director Lloyd Goodrich, by artists like Charles Burchfield, Edward Hopper, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Walt Kuhn, James Rosenquist, and Marisol—the lone lady artist in the bunch.

Architect Peter Blake wrote in A.i.A. that the inverted ziggurat might constitute a “massive attack” against Madison Avenue’s consumerism. It seems a quaint hope, especially after the museum’s uptown swan song was sung by Jeff Koons, whose career is premised exactly upon playing to consumerist glitz. (Of course Koons’s work is more complicated than that, as even the most rabid Koons detractor would have to concede after reading Scott Rothkopf’s catalogue essay, but still.)

(See Jeff Koons as the Art World’s Great White Hope for our critic Ben Davis’s take on that show.)

The museum had strained against its small size for years. In 1985, director Thomas Armstrong failed to push through a 10-story Michael Graves–designed addition that would have demolished several neighboring brownstones (see Postmodernist Architect Michael Graves Dead at 80). Architect Richard Gluckman oversaw a renovation and expansion in the 90s, during Ross’s tenure.

After Maxwell Anderson took over in 1998, he invited Rem Koolhaas to design an expansion that also was not to be. Two months after scrapping the plans in 2003, pleading institutional poverty, Anderson left the directorship, to the relief of Jerry Saltz, who penned an editorial for artnet magazine about what he saw as poor shows and poor management.

Current director Adam Weinberg took the reins later that year, and has succeeded where his predecessors failed, and by going even bigger than they had attempted. Weinberg was previously head of the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy, after a stint as senior curator at the Whitney.

All along, the museum operated numerous branch locations. Most notable was the one at Philip Morris (later Altria), in Midtown Manhattan, which mounted shows of artists including Christian Marclay and Shirin Neshat, but there was also one on Water Street and another in Stamford, Connecticut, as well as displays of holdings in several corporate lobbies in the ‘80s.

“People always say, ‘Isn’t the Breuer building wonderful, and won’t you miss it?’” Rothkopf told Art in America in 2013. “I’m not nostalgic for it, because it wasn’t designed for what museums do now.” The size and ambition of much contemporary art has also expanded dramatically, he added, making the Breuer’s galleries increasingly constricting.

“The Breuer is a great, great building,” Broun said. “It was a passionate, strong, declarative statement for its age, but now we’re in a different age.” While the Breuer has become an icon, most people I’ve asked are hard-pressed to think of another Breuer building, though his 1925 Wassily chair is a classic of modern design.

“With all due respect to Breuer, he didn’t quite understand what the art of the 20th and 21st century was going to demand,” Ross said. “You always had to jerry-rig things to make it work.” Ross knows a bit about museums large and small, having directed the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston from 1982-1991 and the Whitney from 1991-1998, followed by a three-year term at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Of Biennials, Black Males, and Borders

Over its 84 years of programming, the Whitney has mounted countless shows, some praised and some reviled, with its signature biennial providing a lot of the heat and the headlines.

The latest edition did not disappoint in terms of controversy. The show is often lampooned as “the Whitey Boyennial” for its underrepresentation of women and artists of color. The 2014 outing particularly rankled, with white male artist Joe Scanlan’s presentation of performance works by Donelle Woolford, a fictitious black female artist (see Joe Scanlan’s Collaborator on Controversial Whitney Piece Speaks). The Yams Collective, a Brooklyn-based group of black artists, even withdrew a film from a screening in protest (see The Yams, On the Whitney and White Supremacy).

By contrast, the 1993 biennial, overseen by Elisabeth Sussman, was dubbed “pious and arid” by The New York Times’s Roberta Smith, but even she called it “a watershed” for including works that confronted issues like gender, race and AIDS rather than surveying market trends. And “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art,” curated by Thelma Golden, now director and chief curator at New York’s Studio Museum in Harlem, helped to define a decade that saw marginalized voices challenge hegemony.

The biennials have often proved high water marks in terms of institutional recognition of art forms not always given their due in museums, with Lawrence Rinder’s 2002 biennial a prominent recognition of sound art, architecture and performance. (The Museum of Modern Art didn’t organize its first sound art show, by comparison, until 2013.)

Though the Whitney and other museums have long engaged with performance, the 2012 biennial provided a landmark for that art form. That iteration was organized by Sussman along with Jay Sanders, who was later hired as a curator of performance art, the museum’s first. The Bucksbaum Award, which carries a $100,000 grant, went that time around to British-born choreographer Sarah Michelson.

Sussman, in a phone interview, pointed out the museum’s history of landmark shows in the ’80s of artists who came to prominence in that decade, such as Richard Prince, David Salle, Cindy Sherman, and Terry Winters. Several shows in the aughts shed light on ’70s artists who hadn’t quite received their due, she says, like Gordon Matta-Clark, Paul Thek, and Lawrence Weiner. The museum has also organized major shows of figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Glenn Ligon, Agnes Martin, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker.

Fall-winter 2015–16 will see a survey of Harlem Renaissance painter Archibald Motley and a Frank Stella retrospective; on tap for 2016 are a show chosen from Thea Westreich and Ethan Wagner’s collection; work by filmmaker Laura Poitras (of Citizenfour fame) and a David Wojnarowicz retrospective. The next Whitney Biennial has been postponed for a year to March 2017 “to give [the curators] more time to get to know the building,” De Salvo has said.

But the inaugural show chez Piano, “America is Hard to See,” will be a museum-wide reinstallation of the collection, giving it far more space than it ever had on Madison. The title comes from a poem by Robert Frost, via an eponymous 1970 film about Senator Eugene McCarthy by filmmaker Emile de Antonio, known for documentaries that attacked the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon, among other projects. (See Whitney Museum’s Inaugural Show in New Home Spans John Sloan to Yayoi Kusama and Jeff Koons.)

After the inaugural show has come and gone, too, the collection will have far more room to breathe in the Piano building, with 20,000 square feet, the entire sixth and seventh floors, devoted to it. De Salvo pointed out that the fifth floor of the Breuer, where the collection previously resided, was converted from office space and not ideal.

“America Is Hard to See” acknowledges, too, the wiggle room the museum has long granted itself in terms of defining “American” art. De Salvo points out that the museum mounted a 2012 retrospective of the work of Yayoi Kusama, who was born in Japan and lives there now but spent time in the States, mixing with artists like Warhol and Donald Judd. “It’s hard to imagine what Abstract Expressionism would have been like without the artists in exile,” she said.

“Ideas are fluid and they travel. That said, we’ve tried to have some rigor on this, or else it could seem arbitrary. If you examine the loose boundaries through artists in a very specific way, that’s how it has authenticity.”

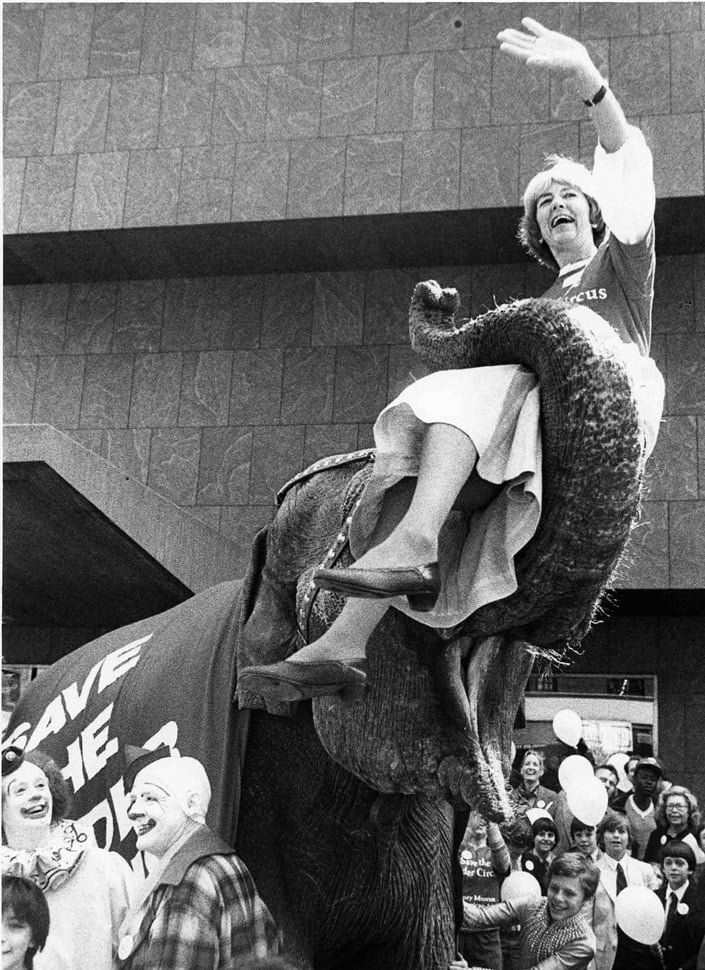

Board member Flora Miller Biddle, granddaughter of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, took a ride on an elephant during a 1981-82 fundraising campaign to buy Alexander Calder’s Circus.

Photo: Helaine Messer. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

The 220,000-Square-Foot Piano

The museum’s new home in the Meatpacking District boasts 50,000 square feet of interior exhibition space plus 13,000 square feet on several outdoor terraces for display of sculpture. Sure to be eye-popping is the fifth floor, an 18,000-square-foot column-free space (nearly two-thirds the exhibition space in the entire Breuer building, which sits on a 104-by-125-foot lot).

As important as the exhibition space, says De Salvo, are the other kinds of facilities that the new Whitney allows, such as a proper auditorium, conservation facilities and an art study center. The museum has invested $422 million in the Piano edifice, which comes complete with state-of-the-art flood protections inspired after the construction site took on 30 feet of water during Superstorm Sandy.

Piano has designed numerous museums, including the Menil Collection, Houston; the Fondation Beyeler Museum, Basel; the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; and expansions at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He also renovated the Morgan Library and Museum in Midtown.

While the graceful interiors of his other gallery spaces may be repeated at Gansevoort Street, though, the exterior design hasn’t inspired much love. Detractors view Piano’s many museum commissions as elegant if safe. New York magazine’s Justin Davidson wrote that the new Whitney recalls a clunky cruise ship; its pale exterior seems to echo the corporate headquarters of the Frank Gehry-designed IAC Building, just a ten-minute walk away via the High Line, but without Gehry’s trademark curves. It might seem like a bit of a comedown after the distinctive design of the Breuer.

“You really have to see it inside and outside,” De Salvo said. “Piano responded to the site. He understood the dynamism of this location. We’re nestled in between buildings, so you have different active facades. It’s almost prismatic in that way.”

Ross’s reaction to the critique of the building’s exterior: so what?

“For me, museum buildings are about what’s inside,” Ross said. “[The new building] is not an elegant sculptural expression like a Gehry or the original Guggenheim or even the Breuer. But the opportunity for a museum architect is not to show what a great sculptor he or she is. The real responsibility is to make spaces that work for artists and publics—not to create some beautiful wrapper.”

The new site at the foot of the High Line is sure to boost attendance, though the museum declined to disclose is projections. Over five years, 20 million people have visited the elevated park. The museum’s peak year for visitorship was 2009–10, with 372,000 visitors, topping an average of about 350,000 annually for the last several years. Even the much smaller Frick Collection, a few blocks away on the Upper East Side, had 420,000 visitors in 2013. So as Ben Sutton wrote for artnet News a year ago, “the Whitney’s brand and reputation … seem to be more popular than the actual museum” (see New Whitney Ready to Take on MoMA and Have New York Museums Hit Their Peak?).

That will likely change now.

Renzo Piano’s Whitney Museum, viewed from Gansevoort Street.

Photo Karin Jobst. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

Options and Futures

After the parties and the inaugural show and the 2017 biennial, the next big marker in the Whitney’s history will be the year 2024—when the Metropolitan’s eight-year lease on the Breuer building is up. Maybe if the Met demonstrates some innovative ways to use the building, the Whitney will get nostalgic after all. The Met’s first show there will survey unfinished works of art since the Renaissance (see Met Announces First Show in Whitney’s Breuer Building).

In the meantime, Storr says that if anything, the Whitney may not be thinking big enough.

“It’s time the Whitney became the museum of the art of the Americas, hemispherically,” he said. “After a long period of myopia about those to the north and particularly to the south of us, we need to be more open to the arts and cultures of this broader zone.”

Presented with that idea, even De Salvo was intrigued, if skeptical.

“It’s a question of how much you can take on and how much you can take on well,” she said. “We do have a certain commitment to artists of the United States, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t be expansive in terms of looking selectively at artists who have come from other places but have some sense of intersection in some way. Various biennials have included non-American figures.”

Bruce Altshuler, director of the museum studies program at New York University, doesn’t disagree with Storr either.

“The museum has struggled since the 80s with the limitations that can be read into the idea that it’s a museum of the art of the United States. These problems can be addressed via the exhibition program.” If they wanted to start collecting the art of the hemisphere, he added, “They might need a few more buildings.”

But then again, the Whitney may one day have two at its disposal.

As much as the museum might have wished to cash out on the Breuer, it couldn’t, after 2008, when cosmetics heir Leonard A. Lauder gave $131 million on condition that it not sell its uptown home. In 2010, the tentative plan was to run two museums, one uptown and one downtown.

“It’s just down to money,” board co-chair Brooke Garber Neidich told the New York Times. The new building demands a fair bit of money itself; it’s supported by a capital campaign that has raised 99 percent of its $760 million goal. Museum officials told the New York Times that they project “a close to 50 percent increase in the operating budget—to $49 million a year up from $33 million.” The museum has also built its endowment to upward of $275 million from $53 million when Weinberg started.

“We’ll start thinking about the Breuer sooner rather than later,” De Salvo said. “The decision to lease was a brilliant one. It allows us to settle here and still retain that magnificent building. We have a period of time to think about it, to be very strategic and also thoughtful about what’s in the best interests of the museum long-term. It’s a very lucky position to be in.”