Photo courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York.

New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art isn’t backing down on a wall label that Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight claims is “flatly false.”

The museum opened in dramatically expanded new gigs in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District on May 1 (see Brian Boucher’s 10 Reasons To Be Excited About The New Whitney Museum, Ben Davis On Why The New Whitney Museum Is So Visually Pleasing But Worrying For Art and Does the New Whitney Museum Herald a Golden Age for New York Institutions?).

The museum has also gained some probably unwanted attention for hanging a Jackson Pollock canvas in an unorthodox way (see Whitney Museum Hangs Jackson Pollock Painting the Wrong Way) and for declining a public sculpture by Charles Ray (Charles Ray Sculpture Rejected From Whitney Plaza For Fear of Offending Tourists).

It all goes back to the 1993 Whitney Biennial, known for including more women and non-white artists than many biennials, and for taking on some of the social, political and racial tensions that characterized that moment. The show even included the notorious video, shot by an onlooker, of Los Angeles police beating motorist Rodney King.

Knight reviewed the show negatively in the Los Angeles Times, and the Whitney quotes sections from it in a wall label as an example of the show’s poor reception by critics.

In his recent article, Knight calls the label “false and defamatory” and says the museum’s defense of it is “Orwellian.”

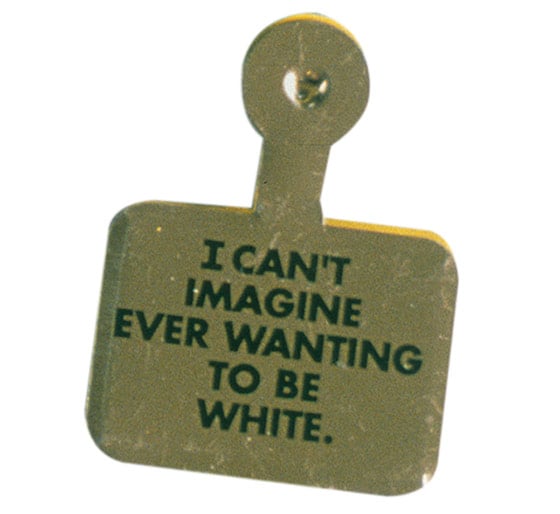

Here’s what the label says:

“’Under the enthusiastic banner of opening up the institutional art world to expansive diversity, the Whitney has in fact perversely narrowed its scope to an almost excruciating degree. The result: Artistically, it’s awful.’ Critic Christopher Knight’s review of the 1993 Whitney Biennial was a typical one, noting the unprecedented presence of art by women, ethnic minorities, and gays and lesbians, while decrying the show’s artistic quality.”

“Wow,” Knight wrote in the LA Times last month. “The museum is claiming that I asserted that art collapsed because the Whitney finally embraced diversity among artists. That’s flatly false.”

Knight goes on to say that his argument at the time was that the museum patronized the non-white, non-male artists it included by focusing on women and minority artists only when their work was politically driven.

The problem is that what Knight sees in the label isn’t there. They key word in his claim is “because.”

The label says that he noted the improvement in the show’s demographics. It also says that he criticized the show. It doesn’t say, as far as I can see, that Knight laid the blame for what he saw as a poor show on the presence of women and minorities. It doesn’t say that Knight called it a cause-and-effect relationship.

The museum has promised to change the label and pleads a delay due to needing an outside vendor to silkscreen the text.

This elicits more sarcasm from Knight:

“Translation: Look at all the trouble and expense we’re going to!

Gee, thanks. Impressive.”

Knight also reviewed the museum’s opening show, calling it parochial—twice, no less—and supporting that by noting some California artists he would have liked to see there.

He’s doubled down in his 1,000-word jeremiad today, calling the museum’s actions malicious, its label a “colossal flub,” an “odious sign,” and a “dumb caricature,” and asserting that it represents an “institutional failure.”