Art World

Artists Are Using the ‘Allison and Warren Kanders Stairway’ at the Whitney Museum as a Site of Protest

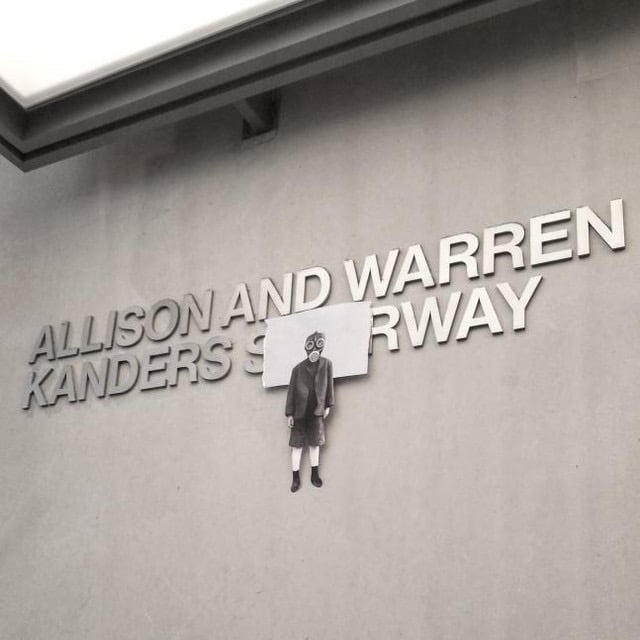

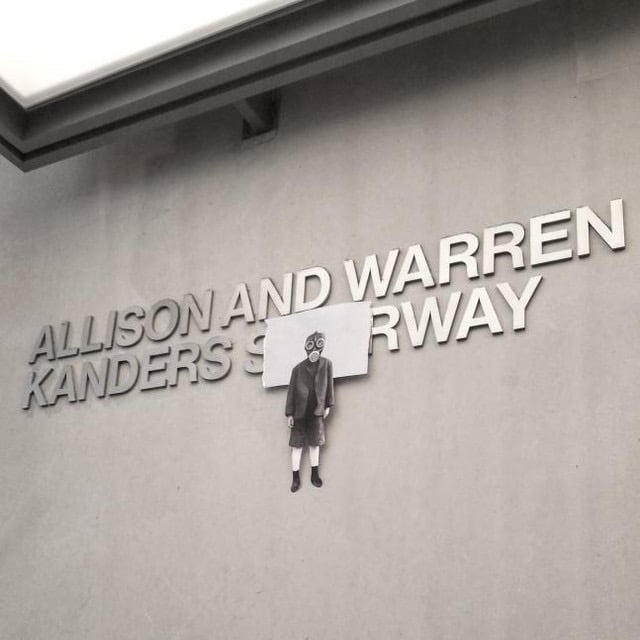

A guerrilla artist targeted a stairway dedication to Warren Kanders at the Whitney.

A guerrilla artist targeted a stairway dedication to Warren Kanders at the Whitney.

Sarah Cascone

When the Whitney Museum of American Art opened its new building in New York’s Meatpacking District in 2015, little attention was paid to the name gracing its main stairwell, officially christened the Allison and Warren Kanders Stairway.

But now that activists are staging weekly protests to make sure that everyone knows that Warren B. Kanders, the vice chair of the museum’s board, owns the the tear gas manufacturer Safariland, two artists have separately made the stairwell a focal point of their work.

This week, as artists began withdrawing their work from the Whitney Biennial in protest of Kanders’s continued presence on the museum’s board, the underground subway artist Jilly Ballistic, who creates contemporary protest art using historical images, installed one of her unauthorized works next to the Kanders name.

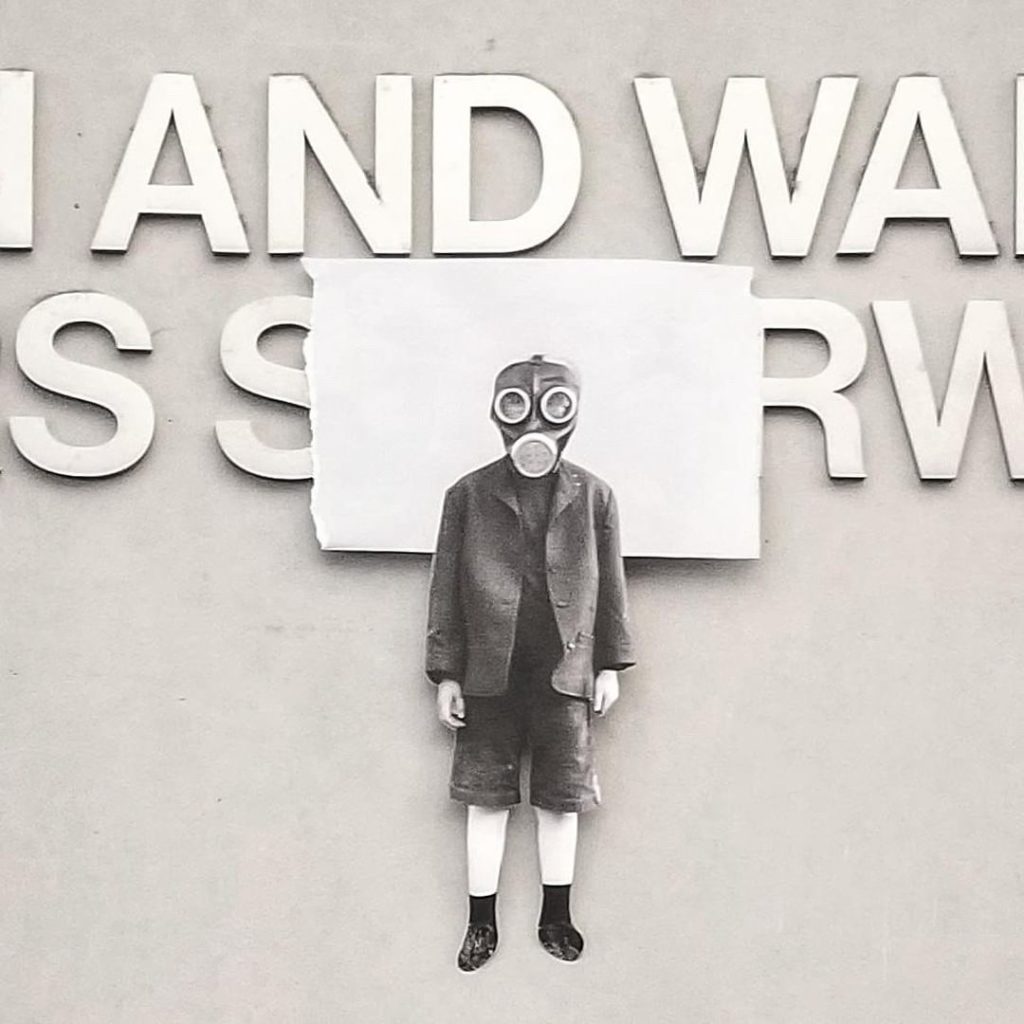

Yesterday, she affixed a black-and-white vintage photograph of a person in a gas mask over the first half of the word stairway in the dedication sign, suggesting that the image represents “the Kanders way.”

Jilly Ballistic targeted the Whitney Museum with this guerrilla artwork calling out board vice chair Warren Kanders’s links to the tear gas used on migrants. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“The Kanders are part of a long tradition of making money out of human suffering and oppression,” Ballistic told New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz in a quote posted on his Instagram. “I use archival images of chemical warfare to highlight the evolution of war, born on battlefield to where we are now, targeting the innocent. As a gay female artist, seeing the marginalized abused has always affected me.”

The stairway is under fairly close surveillance, so Ballastic’s intervention was only up for a few minutes before staff removed it. The Whitney did not respond to requests for comment on the incident.

Meanwhile, 2019 Whitney Biennial curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley commissioned artist Marcus Fischer to make a new work specifically for the Allison and Warren Kanders Stairway, which is also home to Untitled (America), a 1994 sculpture consisting of six-story-long strands of illuminated lightbulbs by the late Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

“[They] wanted me to take on that space and invited me to create something that could be in dialogue with the Felix Gonzales-Torres installation,” Fischer told artnet News in an email.

The audio-based work, (Ascent/Dissent), is 42 minutes long, playing 10 different streams of audio on 30 speakers across the six floors. It emanates an ambient sound that Hyperallergic has described as “an aural metaphor for oppressed communities rising up.”

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (America), 1994, in the stairwell of the Whitney Museum of American Art during the new museum building’s inaugural dinner on April 20, 2015. Photo by J Grassi, ©Patrick McMullan.

Ahead of the biennial’s opening, as opposition to Kanders mounted, the curators offered Fischer the opportunity to pull out of that portion of the show. A number of prominent intellectuals, as well as members of the museum’s staff, had started to push for Kanders’s resignation. The call was echoed by more than half the artists in the biennial in an open letter sent ahead of the exhibition’s opening. (In response, the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, wrote a letter to the staff claiming that the museum “cannot right all the ills of an unjust world.”)

But Fischer declined to pull the work. “I opted to stay and instead created a work that honored the intent and memory of Mr. Gonzales-Torres and also stood in protest of Kanders and his place in that building and his place in the organization,” Fischer said. “For that to go silent would not be true to the intent of my piece.”

“I feel strongly that Warren Kanders does not belong on the board of the Whitney Museum and have been on the record demanding his removal,” Fischer added. He left open the possibility that he could change his mind about appearing in the show: “I’m taking it day by day like everyone else.”

Fischer also has another audio work in the show, Untitled (Words of Concern), which was made the day before Donald Trump was sworn in as president in 2017. It features the voices of artists speaking about their fears, which include such hot-button issues as racism, homophobia, Russia, and gun violence, each reduced to a single, instantly understood word.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (America) (1994), in the stairwell of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy of the Whitney.

“I feel like that piece was given a second life by being included in the biennial,” Fischer said. “The words and sentiment behind them strike me perhaps even harder now than it did in January of 2017, when we had no idea how bad things could get in this country. It is for that reason that I wish for it to remain in place. We have so much more work to do.”

Fischer wasn’t on site when Ballistic installed her guerrilla work. “I am frankly very surprised this is the first time I’ve seen anyone mess with the dedication sign,” he said. “It seems like everyone just walks right past it.”