Art & Tech

How Artists Are Increasingly Blurring the Lines Between Fine Art and Video Games

A new exhibition at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf unpacks the expanded role of virtual reality games in contemporary art.

A new exhibition at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf unpacks the expanded role of virtual reality games in contemporary art.

Dorian Batycka

Where do video games end, and where does fine art begin? If recent exhibitions tell us anything, it’s that the lines are getting blurrier by the day.

At the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf, for example, a new show titled “World Building” looks to unpack the myriad ways in which games have become increasingly enmeshed within 21st-century visual culture.

“I have this intuition that the future of public art is becoming more orientated towards games, and that it will involve large-scale open-source communities inspired by the early ethos of the internet,” Hans Ulrich Obrist, the show’s curator, told Artnet News.

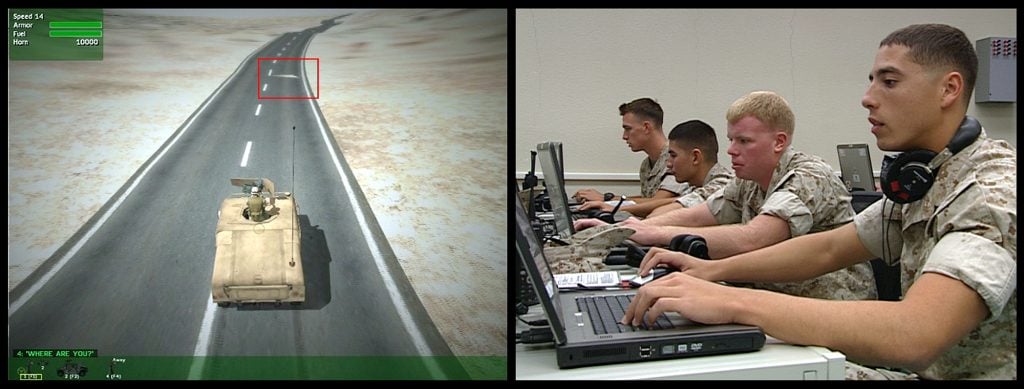

Harun Farocki, Serious Games I: Watson is Down, 2009–2010, video, 8′, color, sound. Video still. Courtesy of Harun Farocki Filmproduction, 2022.

The works on view are vastly different from one another in terms of scale, scope, and purpose, but also in terms of form and function. Some of them are actual games; others are inspired by games. Some are single-channel videos, such as Harun Farocki’s Serious Games I: Watson is Down (2009–2010), a four-part art-house documentary about how virtual reality games are used to recruit and train soldiers.

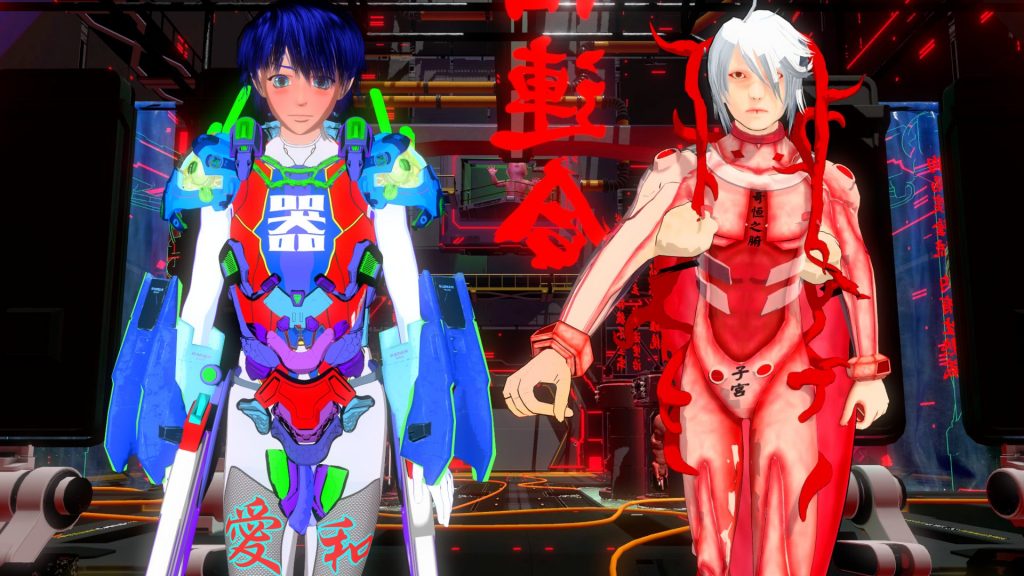

In Lu Yang’s The Great Adventure of Material World (2019), another work on view, players encounter a three-channel installation that, at first, appears like a typical role-playing game, replete with a dizzying array of graphics, animations, quests, and battles.

But players soon realize that the artist has provocatively upended the narrative by forcing gamers to confront characters that shatter the illusion of the game’s narrative structure.

LuYang, The Great Adventure of Material World, 2019, video game and 3-channel video installation, 26′22″, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and Société, Berlin.

A similar experience unfolds in Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s first-person shooter (FPS) installation, SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE (2021), a work that defies the logic of most FPSs. Brathwaite-Shirley’s game tasks players with protecting the environment and making it safe and habitable for Black trans people. Entering the installation, players are prompted to pick up the DECISION MAKER (2021), a pink, 3D-printed gun that acts as a controller, resembling something closer to a body organ than a weapon.

But instead of tasking players with killing, the game asks them to discharge empathy as they encounter fictional characters like Black Trans Water Soul. In Brathwaite-Shirley’s sprawling vision of gaming détournement, players are tasked with performing a meta-dance that confronts their own biases and triggers.

“Video games are to the 21st century what movies were to the 20th century and novels to the 19th century,” Obrist said. “Artists are increasingly developing the technical ability to invent, design, and distribute their own games on all continents to create virtual worlds of diversity and inclusion.”

Sarah Friend, Eve and the Interface (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne/Munich.

Brathwaite-Shirley’s game touches on ideas elaborated by Anna Anthropy in her 2012 book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters.

“What I want from video games is a plurality of voices,” Anthropy writes. “I want games to come from a wider set of experiences and present a wider range of perspectives. I can imagine—you are invited to imagine with me—a world in which digital games are not manufactured for the same small audience but one in which games are authored by you and me for the benefit of our peers.”

Elsewhere in the show, in Sarah Friend’s video Eve and the Interface (2021), the main character moves through a game-like environment tasked with uncovering what appears to be a state secret before eventually realizing that an ominous interface prevents the character from learning more.

The work is an extension of Friend’s research into new forms of platform economy, software, and blockchain social engineering. In Lifeforms (2021), for example, Friend creates what she calls “relational NFT art,” with the value of each NFT only tokenized if it is passed on. Each one is programmed to disappear if it is not shared within 90 days of being received.

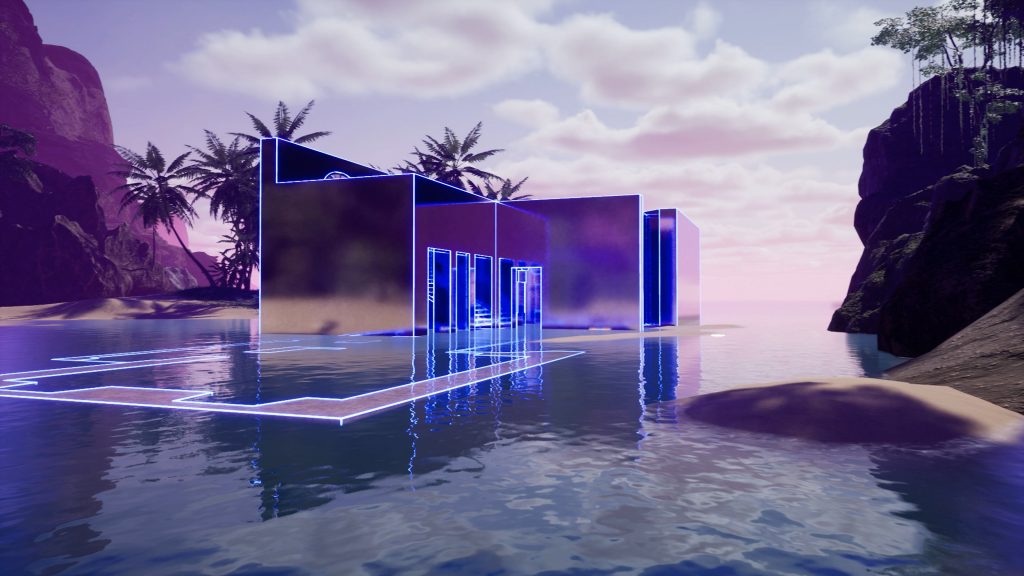

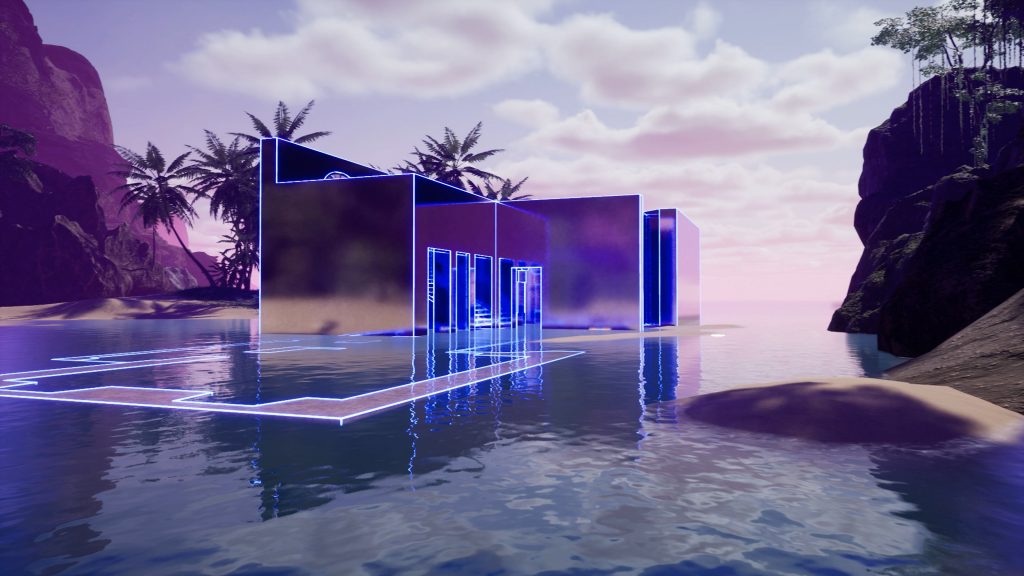

Mythology is another theme that runs deep. In Lawrence Lek’s Nepenthe Valley (2022), for example, the artist has created an installation inspired by the fictional medicine for memory in Greek mythology.

An installation of virtual reality environments allows visitors to encounter a soundtrack of ambient music composed by the artist (fun fact: Lek began his career as a composer of ambient electronic music, and has collaborated in the past with the likes of Kode9).

The work was originally co-commissioned by the NFT platform SO-FAR, spearheaded by Christina Chua, and the virtual gallery AORA for Art Dubai 2022. Ultimately, Lek’s work asks us to stop, pause and reflect, a beautiful addendum to harmony that is constructed around what the artist calls nine “resting spots,” lush mountainous landscapes that come complete with meditation and breathwork sessions, infusing into the ethos of gaming a space for health and well-being.

According to Chua, what prompted her to look more deeply into Lek’s work was the “lore and mythos of games.”

“Games are cultural artifacts,” she added.