Artists

Why Hayv Kahraman’s Women Won’t Let You See Them

The artist's largest institutional show to date at the ICA San Francisco confronts the legacy of colonialism in botany.

The artist's largest institutional show to date at the ICA San Francisco confronts the legacy of colonialism in botany.

Katie White

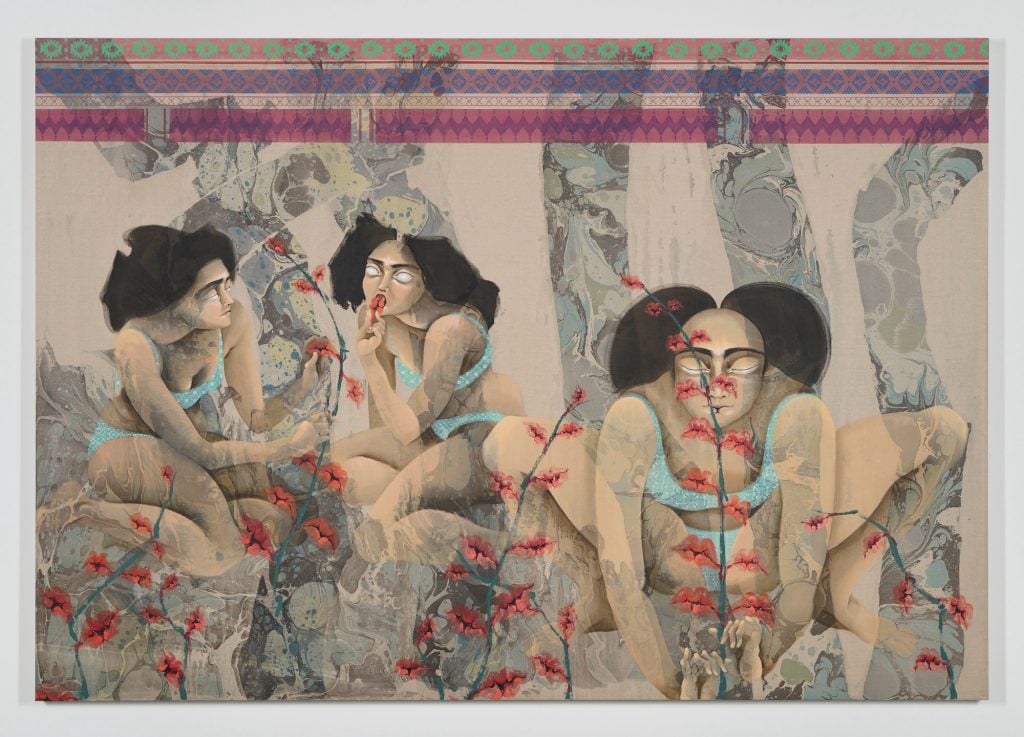

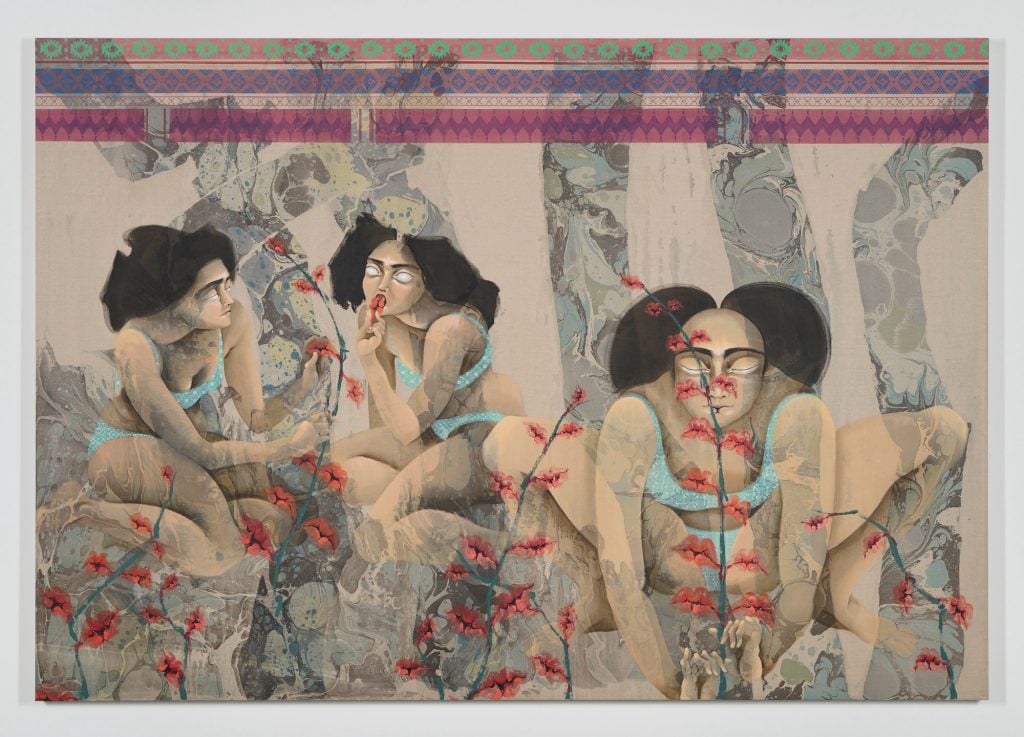

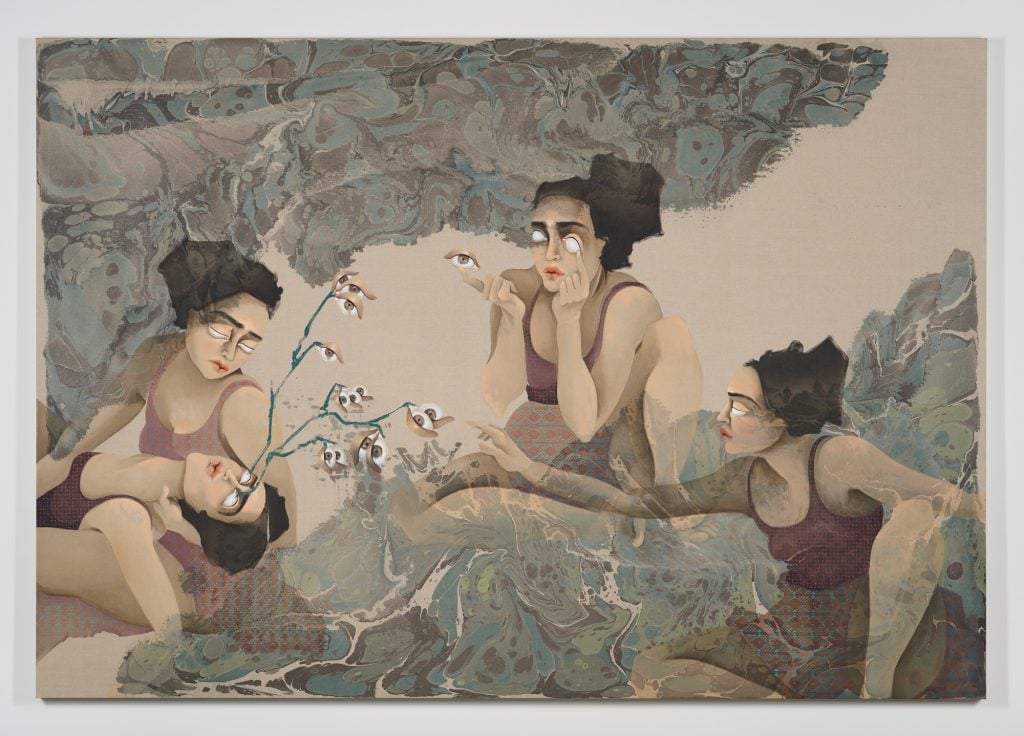

Women stare out from the canvases with emptied eyes—orbs of white nothingness in their sockets. Plants, with vegetal tendrils, grow up between them. The plants sprout lips, eyebrows, and even eyes, though these eyes possess perfect irises unlike the women’s. Swirls of marbled color softly cascade across these canvases like clouds or veils of smoke beneath and around these encounters. These scenes, painted by the Iraqi/Kurdish artist Hayv Kahraman, are eerily beautiful, as these sightless women and unreal plants seem to form an unspoken symbiosis.

Hayv Kahraman, Eyeris (2023). Courtesy of the Artist, Pilar Corrias, London, Jack Shainman Gallery, NY, Vielmetter Los Angeles and The Third Line, Dubai. Photo: Glen C. Cheriton

For the artist, the paintings are also deeply personal, even cathartic. “I’ve lived through two wars in my life. I’ve been an illegal, undocumented refugee in Europe. I was in a marriage with domestic violence for 10 years. I’ve had a lot to work through a lot of trauma,” said the artist on a phone call earlier this year. “Making art is therapeutic for me in general. The new work has pushed me further. I’ve learned I don’t have to have control over everything in my environment. Control was what I thought could keep me safe.”

In “Look Me in the Eyes” the artist’s current exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in San Francisco, the artist is embracing chance for the first time—the results are compelling, raw, and longing visions (the show is on view through May 19; the show travels to the Frye Museum in Seattle this October). These developments have carried through to “She Has No Name” the artist’s concurrent gallery exhibition at Pilar Corrias in London (through May 25).

Hayv Kahraman, Look me in the eyes no 5 (2023). Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, Pilar Corrias, London, The Third Line, Dubai, and Vielmetter Los Angeles

Over the past several years, the Los Angeles-based artist has emerged as a dynamic force pioneering a new figuration with her contorted, fractured, and even surrealist visions of women’s bodies that engage body politics, colonial legacies, and migration. Raised in Baghdad, Kahraman (b.1981) fled from Iraq to Sweden with her family during the Gulf War. Her family crossed “illegally with fake passports and a smuggler.” The artist arrived in Sweden at 11 years old. Her painted women, with their spliced and reconfigured forms, have often been interpreted as oblique self-portraits, and metaphors for the psychic ruptures of life in diaspora.

In this exhibition, Kahraman’s newfound lightness of touch comes through the addition of plant life and the marble swirls of color—additions born of chance encounters. Last year, the artist stumbled upon an article that questioned racial biases in the work of the storied 18th-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, and the lasting implications.

Hayv Kahraman and view of the exhibition Hayv Kahraman: Look Me in the Eyes, Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco, 2024. Courtesy Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco. Photo: Glen Cheriton, Impart Photography

“I was raised thinking, feeling, and believing Linnaeus was an absolute genius. His portrait was on the 100 Krona bill in Sweden. We took field trips to Uppsula. Statues of him were everywhere,” she said. “Reverence surrounded him. But this random article, in very simple language, exposed the colonial legacies he brought to the table. For me, it was as though the blindfolds had come off.” Kahraman quickly began to see the parallels between Linnaeus’s classification of plants and the racial classifications of peoples, particularly immigrants. “I started to think of the plants I felt affinities with,” she said.

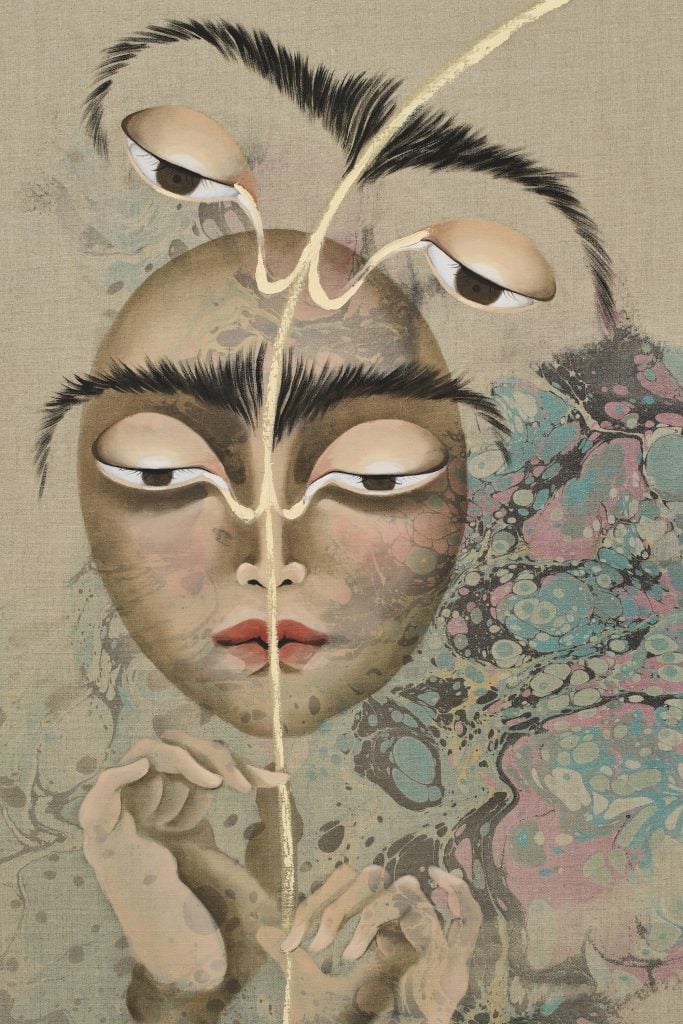

In the exhibition, a series of small paintings of gauche on flax paper, reference plants native to Iraq most often found in California where she now lives, such as botnij, berbeen, and qazwan. “These are all weeds, really resilient plants,” she explained.

Around the same time, Kahraman says she’d become enamored of social media videos of artists marbling paper, an art form dating back to 12th century Japan which she found “mesmerizing.” Then chance intervened. The artist had decided to visit the Huntington Library, a trove of rare books, in Los Angeles, which held Linnaeus’s book Hortus Cliffortianus.

“I thought, okay, I need to just go, open it, and feel the pages on my finger. But when I opened the book and the frontispiece was this incredible marbled paper,” she said, “It felt fated.” The experience led Kahraman to dive into marbling. All the works in the show began with marbling, the artist using a Turkish method, called Ebru.

Installation view of the exhibition “Hayv Kahraman: Look Me in the Eyes” at the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco, 2024. Courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco.

Photo: Glen Cheriton, Impart Photography.

“The most minute thing in your environment will affect your marbling,” Kahraman elaborated, “I found the process incredibly unpredictable. My work had been very controlled before this. It was liberating.” Kahraman also found herself welcoming new, spontaneous imagery into her practice. “I allowed myself to draw and not scrutinize for the first time. The imagery used to emerge from the research. Now eye plants, hand plants, lip plants, finger plants, all began to appear,” she said. For Kahraman, these plants ultimately prodded her to consider, “who we choose to see, who we allow a voice.”

Her recent works, the artist believes, are a way of communicating with her late mother, a homeopath, whose life was reshaped by war and erasure. “She was a naturalist who practiced integrative medicine. She was called in Arabic ‘doctor of herb'” she said. The exhibition also includes an audio component, which draws from a recording of her mother’s interviews with Swedish immigration agents in the 1990s, taken from a long-overlooked cassette. Her mother had petitioned for citizenship five years after their arrival in Sweden but since the family’s documents had been forged she had no way to prove who she truly was.

“This work is my way of reaching my mother, feeling her experience. If you listen to the recording she says, ‘I’m not an insect in your yard’ really speaking to her sense of dehumanization. She was 49 years old and was having to prove her identity. She is pleading. She says ‘Come take a cell from my body,” the artist shared.

Hayv Kahraman, qazwandate (2023). Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, Pilar Corrias, London, The Third Line, Dubai, and Vielmetter Los Angeles.

The paintings also speak to the contemporary experiences of refugees today.

“My cousin works with undocumented minors who come into Sweden, mostly Afghanis. Some of these kids scrape their fingerprints with sandpaper or pour acid on their fingers. They cut their fingerprints. All so they cannot be traced by the European centralized data system,” she explained.

“With new systems, if you seek asylum in one country in Europe and are denied you cannot seek asylum in a different European country. It’s devastating to these people. Now they’re also scanning irises,” she said, “So what do they do? They remove parts of their bodies. In that violent act of cutting, they are trying to circumvent being erased, to avoid being pinned down, categorized just as Linnaeus did to plants. In my past works, there was resistance in the gaze looking back, but there is also resistance in not allowing yourself to be seen.”

Ultimately, she sees these paintings as places of healing, anthropomorphic visions where women heal themselves, through a unification with the natural world.”Eating these plants is a kind of healing, I’m eating this because I’m part of it. Its contradictory and circular at once,” she said.