Art World

Do Outsider Artists Really Exist?

The Outsider Art Fair has brought them front and center.

The Outsider Art Fair has brought them front and center.

Anthony Haden-Guest

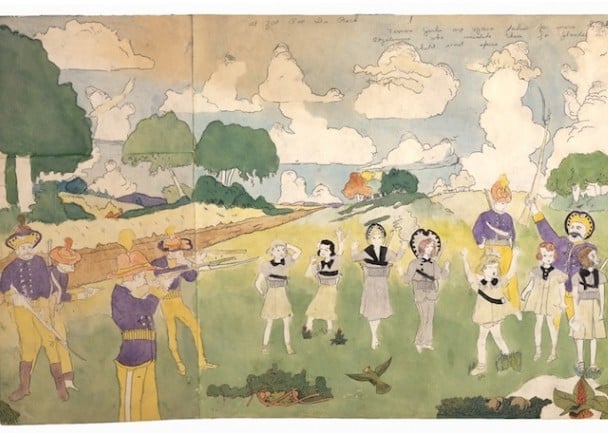

Joe Coleman, Liz Renay (2010).

Acrylic on found triptych.

Image: Courtesy of joecoleman.com.

Days before the Outsider Art Fair opened in New York, artist Joe Coleman was on a panel at NeueHouse, a venue on East 25th which describes itself alarmingly as a “machine for creating.” The supposed theme was Killing Time: The Chronology of Creativity, which sounded enticing, but Coleman, black-bearded and glittery-waist-coated, was in tip-top form, so the discussion—like the screen behind the panelists and the questions from the audience in front of them—focused soon enough on Outsider art.

This is a classification which Coleman went on to denounce as condescending. “I love Henry Darger and Adolf Wofli,” he told the audience. “They are great artists. They aren’t Outsider artists. There’s only good art and bad art.”

Nobody took him up on this. I admire Joe Coleman’s work enormously so I’ll engage with the thorny topic here and now.

There’s a famous story that illuminates the relationship between the Modernists and Outsider artists and it comes from the very beginnings of Modernism. Picasso reportedly bought a canvas by Henri Rousseau in a Paris flea market possibly as early as 1900. In 1908 he threw a banquet for Rousseau which has been described in sometimes hilarious detail. The coats were flung into Juan Gris’s studio, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas were around, there was prodigious drinking; apparently Marie Laurencin got so naughty that Guillaume Apollinaire had to send her home.

It’s clear that Picasso and the young Modernists thought the retired toll-taker was somewhat a holy fool, and, yes, they were condescending, but it’s also clear that they hugely admired his work for its authenticity, its visual inventiveness. And that, as with the African masks they were also looking at, had raw energy, just the energy they needed for their project of dynamiting the salon. (The Picasso banquet was a huge boost to Rousseau’s career as well.)

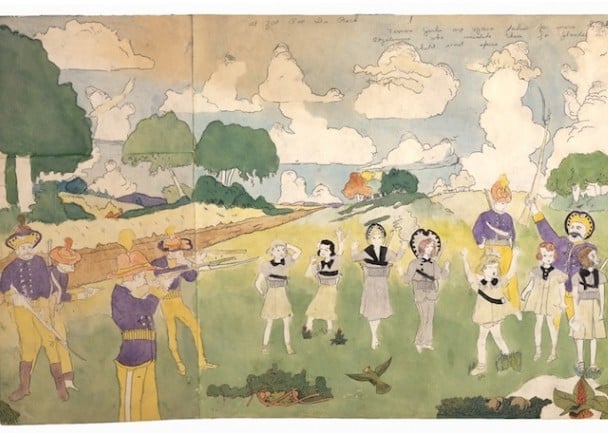

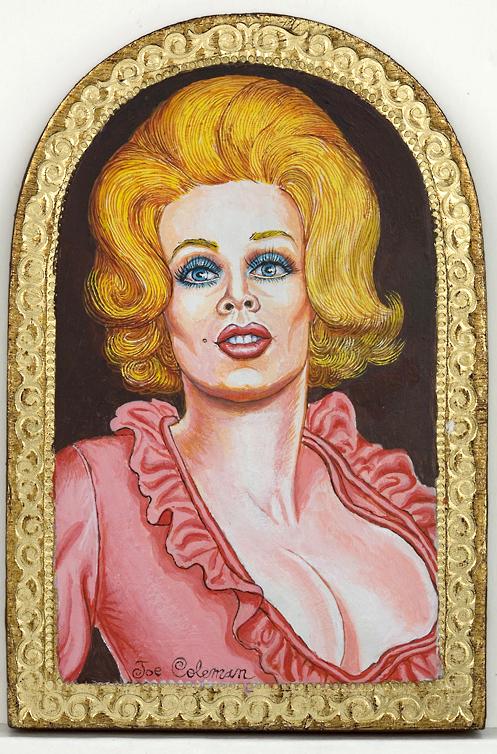

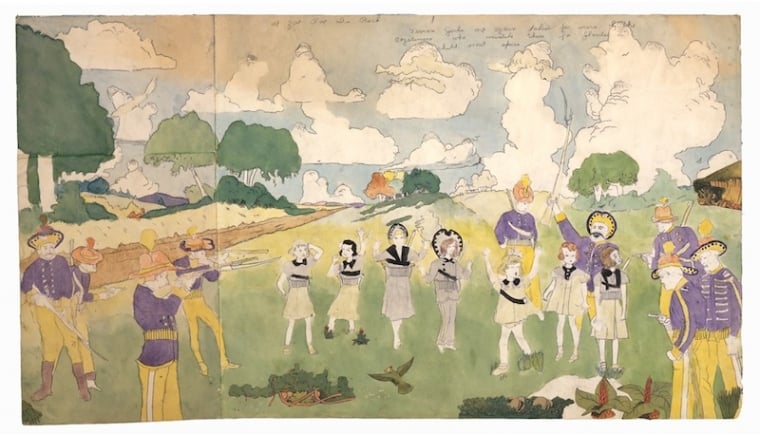

Henry Darger, Untitled (They are chased again however, and have to give up for want of breath).

Photo: Andrew Edlin Gallery.

Outsider art still has that special energy. You could see it, an unmistakeable difference, in the images onscreen at the NeueHouse. Artists like Darger, Wofli and yes, Coleman are different from mainstreamers, but not just because they are schizophrenics (as was Wofli) or have bizarre drives (as most certainly did Darger). Outsider artists are not ‘outside’ just in the sense of being untaught, or disadvantaged, but because they and their work operate outside the Great Game of the art world. And, most important, unlike almost all professional artists, who turn out a fair amount of product—yes, I do include you, Picasso—they mean every thing they do, every single piece they make.

Which is precisely why Outsider art is a focus of such interest right now, a time when a whole new cast of slick derivative tricksters is dominating the artscape. Yes, folks, there’s a whole new Salon out there. That is why prices of the great Outsiders are skyrocketing, and it is why Coleman is perfectly correct in his belief that they belong with the other greats. And they will, in time, join them. Which is also, by the way, why we are seeing a surge of faux, unfelt Outsiderism into the marketplace. But that is an old, old, always depressing story.