Art World

Why ‘Provoking Empathy’ Through Art Might Actually Be a Bad Thing + Two Other Illuminating Reads From Around the Web

A weekly round-up of interesting readings from around the art web.

A weekly round-up of interesting readings from around the art web.

Ben Davis

Each week, countless articles, think pieces, columns, op-eds, features, and manifestos are published online—and not a few of them cast new light on the world of art. I pick out a few each week that might inspire some larger discussion.

On various activist calls in the last few days, people have mentioned the feeling that the energy of the current protest wave has shifted and tempered even as it has won more mainstream support and triggered conversations in countless spaces. I think that’s why Blair McClendon’s essay hits so hard, because it sets out to argue how, specifically, artists and image-makers (McClendon is an award-winning filmmaker) abet the diffusion of that energy via the subtle assumptions they bring in.

McClendon scrutinizes several images that have gained mass exposure in the protests’ wake, including the short video essay that filmmaker Christopher Frierson shot in Brooklyn. In a piece that gained traction in the Guardian and around the world, Frierson showed himself getting pepper sprayed and collapsing in pain, then cuts to himself returning to calmly commune with riot-geared police at the same spot on Flatbush Avenue two nights later, asking their thoughts on what George Floyd’s murder meant to them, and what their feelings are about the protests.

In this documentary gesture of juxtaposed moments—and maybe more importantly, its popularity—McClendon sees a concession to the idea that what has caused Floyd’s murder and the murder of other Black people is some kind of abstract deficit of empathy that might be smoothed out with a credit of nuanced human understanding, if only everyone—police and protesters alike—could simply learn to see each other as people more clearly.

“My fear is that the storytellers have fooled themselves into believing that it is narratives, image-making, representation that offer a way out,” McClendon writes. “They envision reconciliation before the cessation of hostilities.”

A ready-to-hand quote often used to advocate for filmmakers as important in times of crisis, McClendon recounts, is Roger Ebert’s line that film is an “empathy machine.” But whatever real resources storytelling offers in that direction, appeals to “empathy” can also be an ideology, deflecting attention from the stark realities of structures that make violence and oppression inevitable and towards the comforting shores of human-interest stories, personal epiphanies, and beer summits.

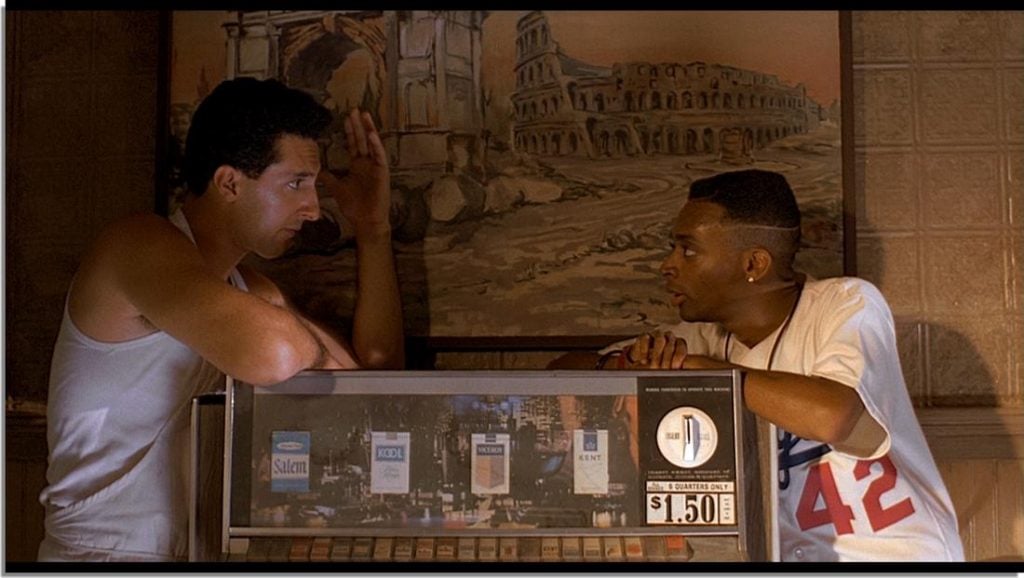

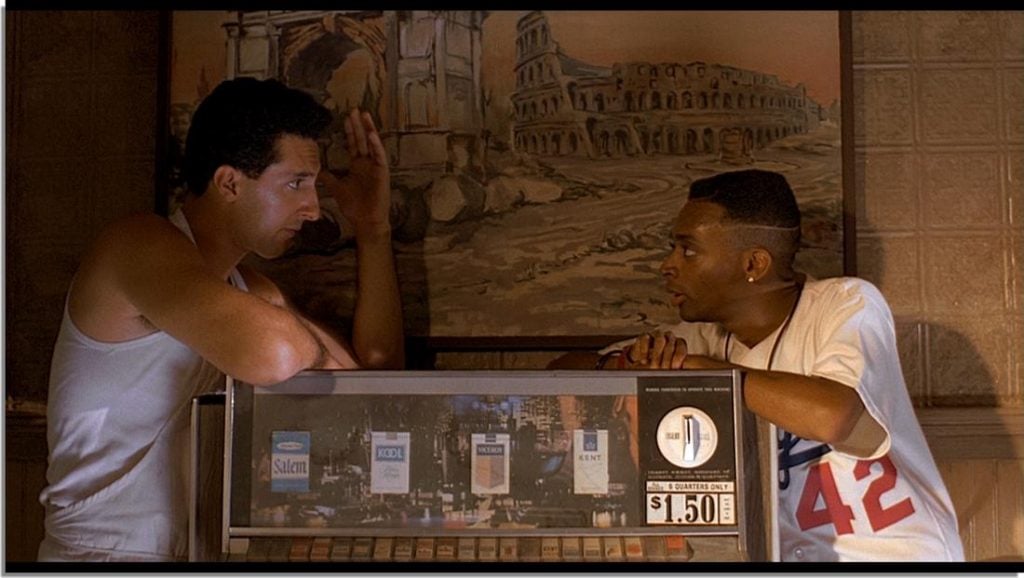

The “empathy machine” trope might also underestimate the thickness of the ideological lenses that people view culture through. The Ebert reference reminds me of the controversy over Spike Lee’s 1989 Do the Right Thing, which the Chicago critic championed, exactly, as a “call to empathy.” Many other critics, meanwhile, looked at the same film and condemned it as a crude “call to violence” against white businesses—seeming to identify with the smashed-up pizza parlor in the film over the Radio Raheem character who gets choked to death by a cop. That gives more ammo to McClendon’s criticism of artistic thinking that “assumes a viewer who was not already subjected to rigorous ideological formation.”

In any case, McClendon is arguing for the need to resist terms of debate that constantly try to reframe the demands of an uprising in the streets into the terms of a professional cultural class:

In these circumstances, filmmakers and our institutions must decide whether we are even serious about responding to white supremacy, or any of the forms of oppression that structure our lives. If we are, we must stop asking what our stories can do. The artist rarely outpaces the people in the streets. We can honor the tremendous risk they have taken on and we can do so by trying to make work that speaks as clearly and honestly about power as the internal movements of our psyches. But we should be humble before the centuries-long persistence and mutation of this deadly idea and we should be humble before the actions of a group of people in Minnesota who made it feel as though a new world was possible. It is a good thing that there has been some movement in the last decade towards increasing diversity in the industry, but if black people are going to take to the streets every summer, risking their freedom and their lives, the great change cannot be the lives of professionals and what gets greenlit. … We cannot fall into the trap of believing that a system willing to humiliate, harass, gas and murder fears a good movie, much less a rise in the ambient levels of empathy. “What can we do?” already admits a realm of impossibility. It is better to ask “what are we willing to do?”

Moniqa Estrada and John Anthony Lopez attend a candlelight vigil in Tiguex Park for Scott Williams, who was shot and seriously injured by counter protester Steven Baca during a protest to remove a sculpture of conquistador Juan de Oñate at the Albuquerque Museum on June 16, 2020 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo by Paul Ratje/AFP via Getty Images.

Last week, artist Scott Daniel Williams was shot and sent to the hospital by Steven Ray Baca, a militantly pro-police former politician. Baca (along with members of a white militia) had taken it upon himself to defend the statue of Juan de Oñate, often known as the “Last Conquistador,” in Albuquerque, New Mexico, as protesters—Williams among them—sought to haul it down. Candice Hopkins, a curator, and Raven Chacon, an artist and musician, give a glimpse into who Williams is on the Albuquerque art scene, outside of this enraging and alarming incident. And it’s not just human interest, either: you should read it to get a sense of someone who has both created community through art and done the work to show up politically and build solidarity.

There’s a GoFundMe, incidentally, for Williams’s hospital bills, here.

18 issues of QUARANZINE distributed in Parkview Park on School and Avers in Chicago. Image via Public Collections Tumblr.

For the last few months, Chicago’s indefatigable Marc Fischer has been publishing Quaranzine, “a printed space for creative work produced during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Taking the form of a two-sided handbill on colored paper, each issue has featured a poem, a political essay, a sketch, a diagram, or a cartoon from a different contributor. It’s been a space to invent, and a place to vent. Fischer concludes the project (for now) with issue 100, “the most boring issue to date,” which serves as an index of all the previous issues. You can browse them all on Fischer’s Public Collections Tumblr.