Art & Exhibitions

Rediscovering the Sensual Multiculturalism of Wifredo Lam at Centre Pompidou

Lam's work is key to the history of Modern art.

Photo: courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska

Lam's work is key to the history of Modern art.

Emily Nathan

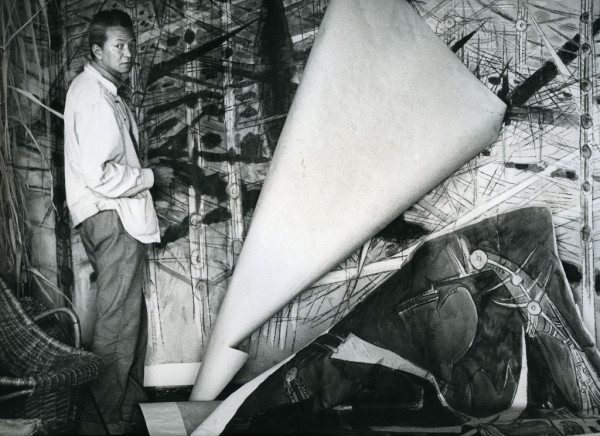

Portrait of the artist in Albissola, 1963

Photo: ©Archives SDO Wifredo Lam

Born in Cuba in 1902 to a Cantonese father and a mother of African slave and Spanish ancestry, Wifredo Lam was always a multicultural creature. During his 80 years, he traveled widely and broadly, settling in innumerable cities that included Madrid, Malaga, Barcelona, Paris, Marseille, Caracas, Albissolla, Zurich, Havana, and Haiti, and befriending a panoply of Modernisn’s forefathers, from Pablo Picasso, André Breton and Asger Jorn to the writers Pablo Neruda, Nicolás Guillén and César Vallejo. While Lam’s early works reveal a solid technical foundation—he moved to Havana at the age of 14 to study painting, and later continued his education in Madrid—it is nearly impossible to summarize his visual style, which evolved over the decades both in and out of step with the movements of the time.

Open since September 30 at Paris’s Centre Pompidou and curated by museum director Catherine David, the comprehensive retrospective explores the nuances of Lam’s creative production over the course of nearly six decades. Galerie Gmurzynska, which exclusively represents Lam’s estate, has loaned several pieces for the show, and Lam’s famous piece The Jungle is on loan from the MoMA for the first time. “[The exhibition] ends with the largest scale painting, Untitled (1958) which references The Jungle but is fully abstract, having been painted when Lam encountered Jackson Pollock. This retrospective will be a game changer for the appreciation of Wifredo Lam,” Mathias Rastorfer of Galerie Gmurzynska told artnet News.

Wifredo Lam Sans Titre (1958)

Photo: courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska

Featuring 450 paintings, drawings, collages, photographs, reviews and rare books, the exhibition is organized in five chronological sections that correspond to geographical phases in Lam’s career, each bearing the stamp of the places, artists, writers and thinkers who influenced him at the time.

“Spain, 1923-1938” introduces Lam as a young student in Madrid, where he moved from Cuba to attend the Royal Academy of Art. His solid traditional formation and the influence of the Old Masters he encountered at the Prado is evident in a pair of meticulously rendered lead-pencil drawings on sepia-toned paper, both depicting Castellanos, both from 1926 and 1927. But Bodegon II (1930), executed just two years later, is shockingly different. With its ambiguously dream-like shapes and forms—stairs leading nowhere, figures with clocks for heads—the canvas marks a conscious departure from Lam’s classical education and a turn toward a more avant-garde narrative and visual voice, evoking the nonsensical Surrealist compositions of Giorgio de Chirico, Juan Gris, and Miró, and the gestural power of Gauguin and Matisse, whom he discovered in 1929.

The 1930s was a period of political and personal upheaval for Lam, who lost both his infant son and his wife to tuberculosis in 1931 and soon thereafter enlisted to fight alongside the republicans in the Spanish Civil War. His Spanish works from this period are dark and shadowed, full of tortured, monstrous forms that approach the grotesque; in 1938, Lam set off for Paris and was quickly integrated into the intellectual domain overseen by Picasso, who became his close friend and mentor. Paintings such as Le Réveil I (1938) share the wooden, mask-life forms of Picasso’s landmark composition Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, integrating the distinct influence of African statuary that was operating in Paris at the time with figures and spaces that are increasingly Cubist.

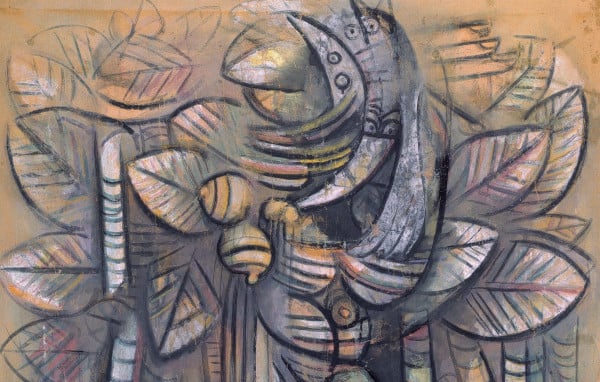

Wifredo Lam Lumière de la forêt (detail), (1942)

Photo: Centre Pompidou, Georges Meguerditchian, Adagp, Paris 2015.

The invasion of Paris by German troops in 1940 drove Lam to Marseille, where he met André Breton and the Surrealists, and after 18 years of life in Europe, he returned to Cuba for the first time since his childhood. It was a tragic homecoming, as he found his native land had been consumed by racism and corruption, so he resorted to depicting elements of the world he still felt connected to, in particular the animal and the vegetal. Lumiere de la Fôret (1942), Autel pour Yemaya (1944), and La Jungle (1943), on loan for the first time from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, present lanky figures that transform into tree trunks and stems of bamboo, bathed in shifting, colorful light that erases boundaries between figure and landscape.

In the ensuing decades, Lam would continue his peripatetic life, exploring Latin America and working alongside ethnologists Lydia Cabrera and Fernando Ortiz as well as the writer Alejo Carpentier, all of whom had dedicated themselves to the history of Afro-Cubanism. He eventually returned to Paris, met Asger Jorn of the CoBRA group and discovered ceramics, travelling to Egypt, India, Thailand, and Mexico before he died in Paris in 1982.

Wifredo Lam The Jungle (1943)

Photo: The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence. Adagp, Paris 2015.

Ultimately, though he never succeeded in determining what exactly comprised his own “Cubanness,” the works he created over a vastly prolific lifetime managed always to bridge the complex interstices between landscapes, cultures, languages and populations, speaking in a language that was as universal as it was singular.

“Wifredo Lam” is on view at Centre Pompidou, Paris from September 30, 2015 – February 15, 2016