“You’re on your own,” is the fateful line heard over a walkie-talkie in the opening moments of Inside, a new art world thriller that recently had its world premiere at the Berlinale film festival. The simmering plot, directed by the Greek filmmaker Vasilis Katsoupis, sees actor Willem Dafoe play Nemo, a destitute thief who struggles to survive in a luxury Manhattan penthouse after a botched art heist. He’s completely alone, save for a couple of exotic fish in a tank and a few millions of dollars’ worth of art.

Dafoe’s thespian display of suffering in a film that runs just shy of two hours is liable to make anyone squirm, but if you are the kind of person who panics in tight spaces, this may not be the movie for you. Inside is a classical survivor tale, but unlike Gilligan’s Island or Castaway, it is brilliantly transposed into a metropolis, within the backdrop of the icily contemporary home of a cultural one-percenter. Unlike the films of this genre that came before it, nature is not the antagonist—modernity is.

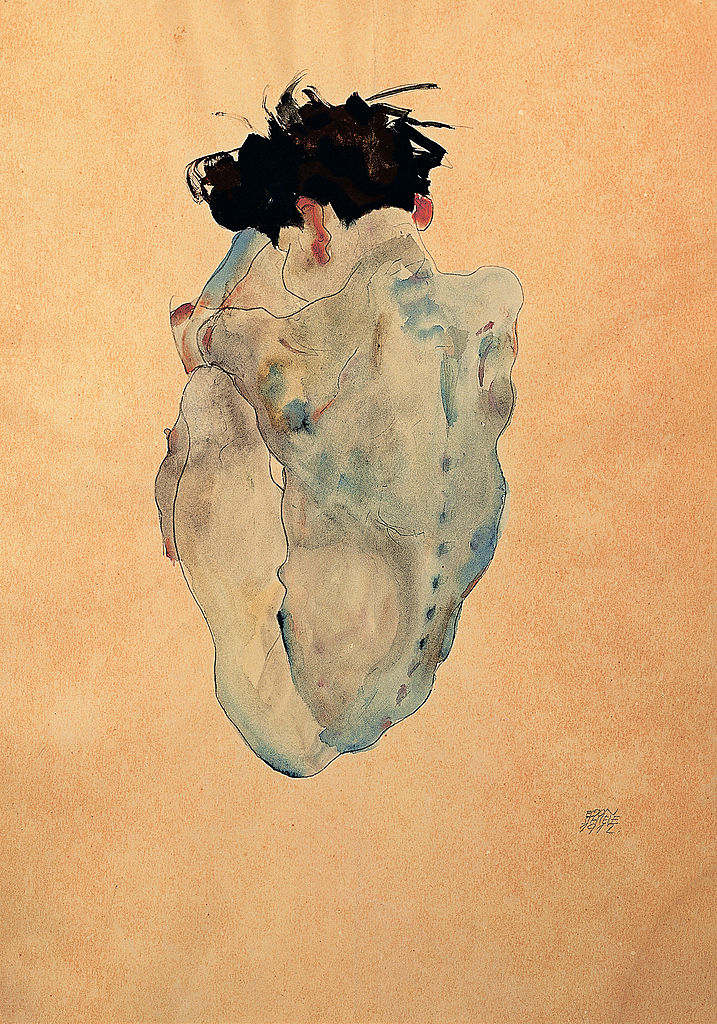

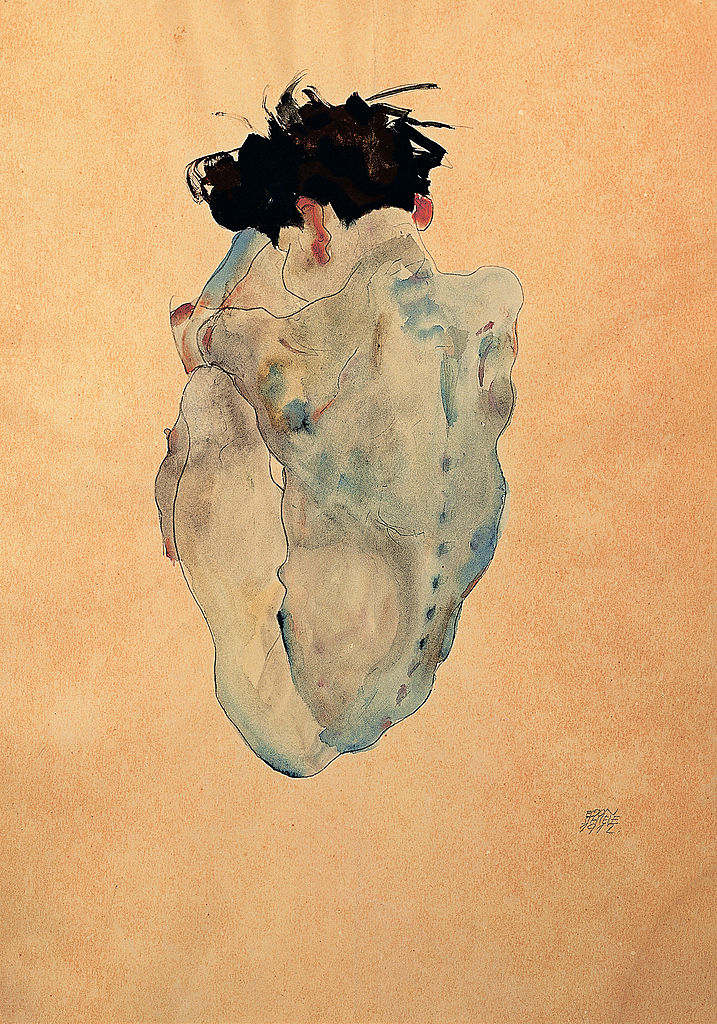

There are few people who can hold the attention of an entire movie theater while being virtually the only actor on-screen—for this, Dafoe is a rare and well-cast talent. And while Nemo bears his soul to us, we learn little-to-nothing about his backstory; all we know is that he was dropped onto the roof of the New York flat by a helicopter to rob an unnamed Pritzer Prize-winning architect of his Egon Schieles. Keeping Nemo as a shadowy archetype is a smart decision, giving the film a symbolic edge that makes it sit outside of time.

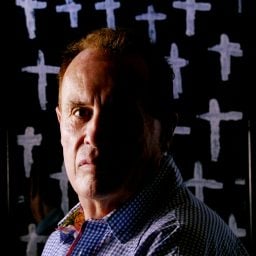

Willem Dafoe stars as Nemo in director Vasilis Katsoupis’s Inside, a Focus Features release. Photo: Wolfgang Ennenbach / Focus Features.

Instead, we learn more about the collector who owns the penthouse palace that becomes Nemo’s prison. The owner has a daughter who lives with him, and a dog. He is away in Kazakhstan. Nemo picks over the last of his groceries, which includes organic canned goods and semolina pasta. What we know most about is his formidable art collection, one which includes emerging artists like Joanna Piotrowska (who had work included at the Venice Biennale last year) and Petrit Halilaj. There are also works by Maurizio Cattelan and John Armleder. There is a rare book by William Blake. If our homeowner is buying at fairs, we’d be seeing him at TEFAF New York and Art Basel in Switzerland, and dialing into the odd Christie’s evening sale, I would guess.

With the aim to build out a convincingly realistic art collection, director Katsoupis hired a curator for the set—Leonardo Bigazzi, who is based in Florence at the Fondazione In Between Art Film. Bigazzi’s carefully selected are all authentic, on loan from the artists and their galleries; some are even new commissions, among them an eerie watercolor by Francesco Clemente called After and Before (2021).

The apartment itself exudes an anthropomorphic persona. The fridge, in a welcome comedic moment, sings out “Macarena.” The penthouse is on the whole an antagonist, becoming a torturous microclimate for Nemo. The malfunctioning alarm system begins heating the luxury home, tensing up the plot as the temperature creeps up degree by degree climbing to a deathly 42°C (107.6°F), before starting to drop again so low that Nemo can see his breath. The water system has been turned off, and so Nemo lies between tropical plants in a purpose-built garden to drink and cool his body.

All the while, artist Adrian Paci’s Centro di permanenza temporanea (2007) looms on the wall—depicting migrants standing on an empty gangway, seemingly waiting for a plane that is absent from the picture. The film’s commentary on climate change is sharp and incisive, but thankfully stops short of being preachy.

Egon Schiele Cowering (male nude) (1912). Private collection. Photo: Gerhard Trumler/Imagno/Getty Images.

The emphasis on the art collection, which lingers as a stand-in for the absent homeowner, begs a question: How much can you know about someone if all you can basically see is the art they buy? And what happens to the value of art when the world around us is basically snuffed out? It turns out not much on both counts. The art is rendered absurdly inutile to Nemo; it looks on lovelessly as he suffers.

The preservation of Schiele’s drawings behind glass seem almost violent when compared to the rapidly deteriorating well-being of our protagonist. It recalls the core message behind the climate activists’ attacks on art last year. In another break of humor, Nemo seems to realize the art does not matter whatsoever; he knocks over a few works by Maurizio Cattelan.

Out of this sterility of art in the face of an emergency, however, Nemo’s own artistic creativity comes forward as a savior of sorts. He builds a sculptural stack out of the homeowner’s furniture; he sketches what he sees to pass the time. Within his brutalist architectural cage, the symbolism of the artworks curated into the film begins to finally evolve as Nemo builds up his own symbolic universe with a charcoal wall drawing and an ever-evolving shrine. The symbology of wealth of an art collection fades into the background and the essence of the works finally emerge.