People

‘It’s Dangerous and Difficult’: Artist William Kentridge on the Challenges for Young Artists Facing Quick Fame and Market Speculation

The South African artist discusses the upsides to a slow-burning career and making art at the periphery.

The South African artist discusses the upsides to a slow-burning career and making art at the periphery.

Devorah Lauter

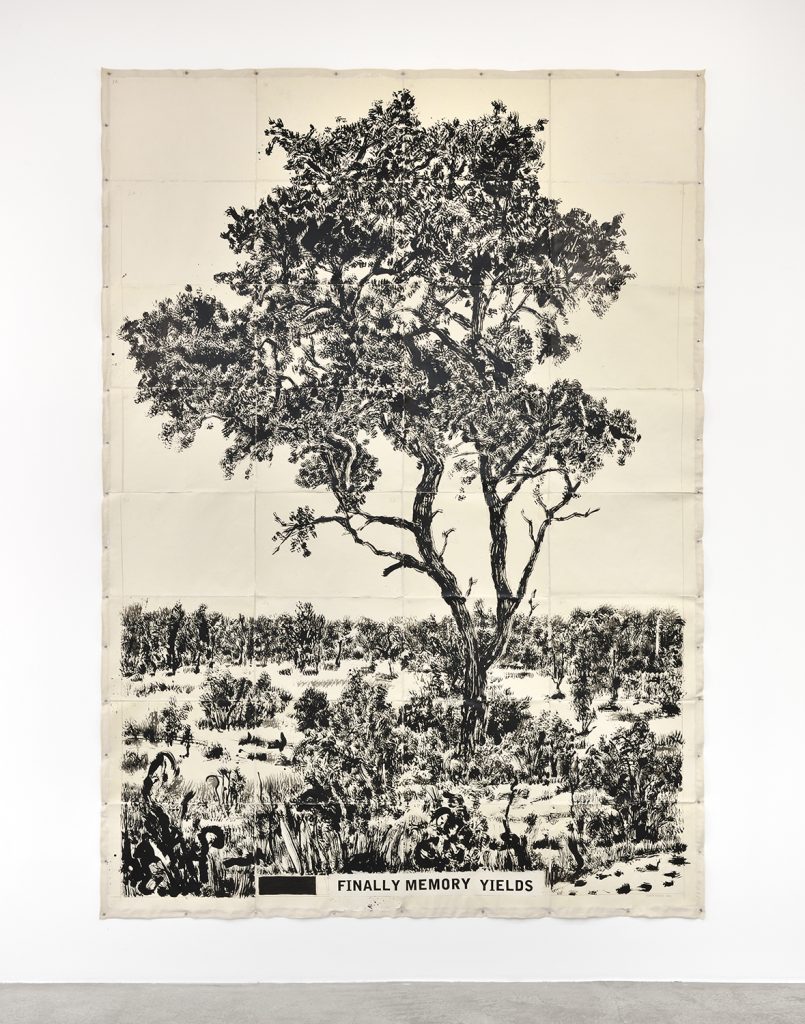

William Kentridge can’t tell you what the title of his current show in Paris, “Finally Memory Yields,” is about. He doesn’t know. That’s why he chose it.

“Does it mean that your memory stopped working or that it gives up? Or is it about the repressive memory yields, and what it reveals that’s inside?” asked Kentridge, speaking to Artnet News at Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris a few days before the opening of his show this week, which runs concurrently with FIAC until November 27.

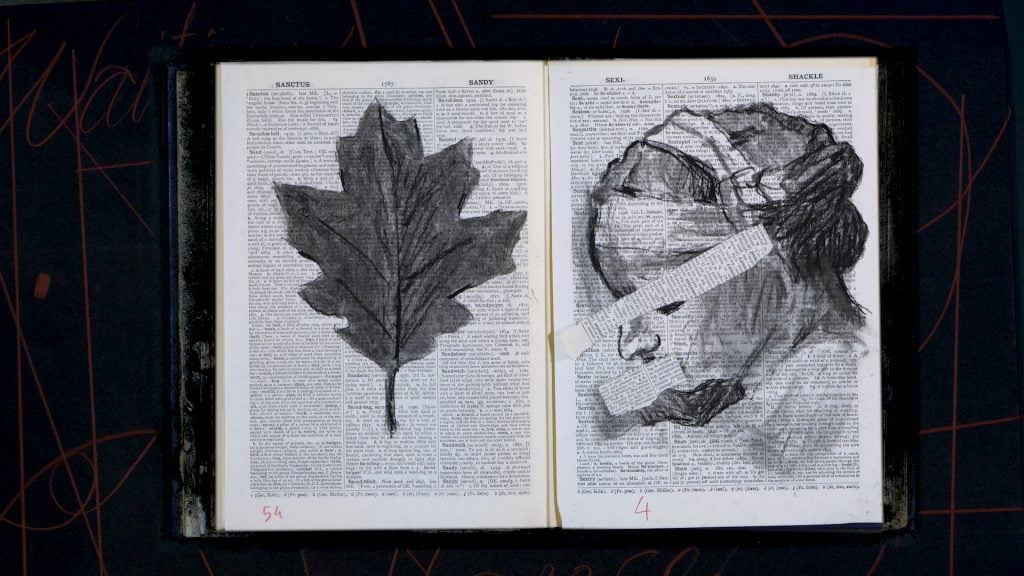

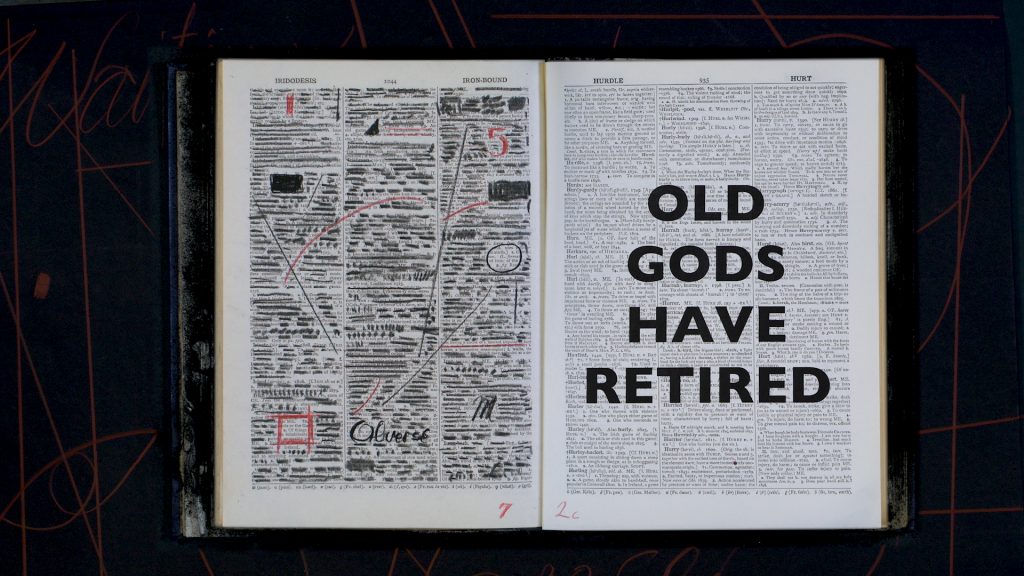

The 66-year-old South African artist has had a storied career, well-known for his massive portfolio of pulsing charcoal drawings, animated films, and operas, which respond to the dark legacy of apartheid and the passage of time with bewitching poignancy. His current show features large ink drawings of trees and his recent film Sibyl, which questions fate—the work was developed from his chamber opera Waiting for the Sibyl, which premiered in the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma in Italy in 2019.

At this advanced stage in his career, one might assume Kentridge has all the answers, but a welcoming attitude to uncertainty and ambiguity are at the heart of his practice and way of life. In today’s shifting cultural context, Kentridge spoke to Artnet News about the pressures of the art industry on young artists, identity politics, and the need for freedom to make art about any subject while taking responsibility for it.

William Kentridge Finally Memory Yields (2021). Courtesy Kentridge Studio and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo credit: Rebecca Fanuele.

Throughout the exhibition and in its title, there’s this recurring idea of letting go. What does that mean for the work and your practice?

It is about allowing things to take their shape—I’m not quite sure why all these trees are being drawn. In one sense, they’re long-term self-portraits. I read somewhere a description of death that said we all grow our tree of death inside us. It starts growing when we’re born, and we have to hope that we’ll live long enough for this tree to be a great, beautiful, strong tree, before it comes through us.

Are you letting things go now in your work—are you taking new directions?

I wish I was taking more new directions. There are always new drawings and there are new techniques and new ways of working. I’m working now on a series of films about life in the studio—that is my big lockdown project.

You think you’re doing a new drawing and then you make the drawing and realize that you’ve drawn that 11 times! I made two lists once, one of things I haven’t drawn and one things I have drawn. I said that for a year I can only draw the things I have never drawn before. The second day, I was back on the first list. So it’s not just a question of will. It’s a question of what things call to be drawn. What things meet the drawing halfway? What things seem to throw themselves onto the page?

To maintain a long-term drive as an artist, is the studio the answer?

For me it is. There’s no doubt that it’s easier to keep working every day after 40 years than it was in the first five or 10 years. It was much harder to find the confidence to keep going. Finding the need and the energy to keep working became easier. It was very hard in the first years to know if this was just a kind of therapy that I was doing. Is anyone ever going to be interested? Did I have anything to say?

William KentridgeSibyl (2020) (film still). Courtesy Kentridge Studio and Marian Goodman Gallery

Copyright William Kentridge.

Was there a turning point where that changed?

After I’d had some exhibitions, I then decided I didn’t have the right to be an artist. I felt I had nothing to say and that there was no reason why I should be doing this. So I stopped for several years and went to theater school in Paris and tried to make movies. In spite of myself, I was back in the studio. Then I said, “Well, what the hell. I’m not going to really think about what I should be doing. I’ll see what happens.” There was a great lifting of pressure. That was between about 1981 and 1985 when I was between 25 and 30. In retrospect, it was great to have these uncertain years. When I came back to art, I knew that’s what I really wanted to do.

I can’t know if that coincided with the birth of our first child or with my parents leaving Johannesburg and moving to England, which happened more or less the same year. Whatever it was, at that time, there was a huge relaxation. I could now make art for myself, and if it was interesting for me and a couple of friends, then it had to take its chance in the world. That’s kind of been the principle of working since then.

Do you think the situation is different for young artists today from what you experienced?

I think it’s very hard for younger artists now. There’s a sense in some parts of the world that if you’re not picked up by a gallery in your final year of university, you haven’t made it. That’s tagging onto the edges of the tech world where if you’re not a billionaire by age 30, you’re a failure.

Of the young artists that suddenly become very hot very quickly, it’s dangerous and difficult. There’s a pressure to say: “This is what we can sell, so please go on making this.” You can get trapped into quite a narrow band of what’s expected of you. As soon as it pauses for any moment–and it does—you must have the strength to say: “I’ve got another 50 years ahead of me, let me keep working through it.” If success comes quickly and early, you don’t know if you’re doing it because you can do it and it seems to work, or if it’s what you really need to do.

It was very good for me to be an artist at the periphery in Johannesburg and not in New York, Paris, or London. It meant I could quietly develop a strange way of working with animation and figurative drawing, and all the things that weren’t popular at the time when I was doing them. Because there was no anticipation of being part of an international art conversation and because of the cultural boycott of South Africa, it was possible to not be terrorized by what is expected in the center. I did not have to ask, “Do I have to look at art in America to see how I should be painting?”

William Kentridge Drawing for Waiting for the Sibyl (Geometry of Colour) (2021). Courtesy Kentridge Studio and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo credit: Rebecca Fanuele.

How do you navigate art market speculation?

One absolutely relies on one’s dealer being able to judge whether someone is buying your work because they have a real interest in it or is buying it because they want to churn and resell it. You must hope the gallery and you both have the good sense and the patience to avoid the pitfalls. It’s not easy. Being a dealer is really one of the long-term arts.

On the note of speculation, what about NFTs? Do you have an opinion?

I’m kind of intrigued by them as a strange phenomenon but I’ve kept my distance. The remarkable thing is the huge amount of money spent on really bad art. It seems at a much higher rate [for NFTs] than in the conventional art world, where there’s still the real danger of art being turned into a forum for speculation. That’s always been at the edges of what happens in the art world, but it seems to be the raison-d’être for NFTs. It’s about trading and doesn’t really matter what the image is if you can somehow persuade people that it’s a rarity. There’s definitely more than the whiff of a Ponzi scheme in the NFTs. I’m sure there are many smart people saying that the artwork is speculation.

Circling back to your show, the works on view address fate and our desire to know what will become of us, which is appropriate with all the changes we’re going through right now.

The idea that if you’re in the Western World, you’re assured of a calm, long life immune to sudden disasters… Covid-19 has certainly shown that sudden and violent ends are a daily possibility. Whatever wealth you have, whatever private security guards you have, you’re still vulnerable.

The one thing that Covid-19 has shown us is that claims to authoritative certainty about how the world operates are very thinly based. The question of uncertainty, ambiguity, and doubt is the bedrock of what happens in the studio whether you’re a writer, a singer, or visual artist. In my film [Sibyl], that is the condition of the world that we’re in—not knowing.

William Kentridge Sibyl (2020) (film still). Courtesy Kentridge Studio and Marian Goodman Gallery

Copyright William Kentridge.

Regarding perceptions in the Western World, can you comment on the “cancel culture” or identity politics we’re experiencing today?

There’s a whole new etiquette of things you can say and can’t say. It’s made for a great fear amongst academics. The academics, not only of my generation, but of a younger generation live in fear of misspeaking and having to know what will and won’t trigger. In the studio, that’s not the case. It works in a very different space.

What does it mean for art-making? What is a person allowed to make art about today?

I think there needs to be an openness to what images you make but once an image is made, you have to take responsibility for it.

While things give offence and some artists love pushing those boundaries, that’s never seemed like the most interesting thing to do. But there’s no doubt having said that we live in a very Puritan, quite repressive era.

I make art about things that interest me and provoke me. I never think that I’m talking on behalf of anyone else. For a writer, more so than for a visual artist, there’s the responsibility to imaginatively place oneself outside of one’s own position. But I’m not a novelist, so all the films that I’ve made, I’ve made knowing they had to be made from my perspective. It’s not out of a moral imperative, but out of a lack of imagination.

Can one cover history? Can one look at different kinds of injustice? It would be absurd to say that one can’t look at those subjects. To say, “Social comedy amongst the white middle class—that’s your allotted subject.” That would be intolerable and would make for very bad art. In the same way, to say to a young black woman: “your territory is young black women, don’t go anywhere else.”

I think one of the things that the years of fighting against Apartheid gives one: a very strong and healthy skepticism of all identity politics. The fight against apartheid was for a kind of universalism. It was about saying everybody is entitled to listen to different kinds of music, to read books, to live in different places, to choose to be who they want, rather than to say that classical music only belongs to whites or township jazz only belongs to Black people. One of the fights over all these decades was to try and find—I know it’s unfashionable to be a humanist—a broader sense of connection across people.

William Kentridge’s “Finally Memory Yields” is on view at Marian Goodman in Paris until November 27.