People

With Four Shows Opening Across New York, 82-Year-Old Video Art Pioneer Peter Campus Is Having a Moment. Here’s Why

Forty-five years ago, the artist predicted that we would one day live out our lives on screens.

Forty-five years ago, the artist predicted that we would one day live out our lives on screens.

Taylor Dafoe

It’s estimated that the average American spends more than three and a half hours on their phone each day. We consume information, interact with one another, and project our sense of selves through the screen.

Forty-five years ago, artist Peter Campus foresaw all of this, exploring then-nascent video technology as a way to investigate himself. With his distinct mix of recursive minimalism, psycho-surrealism, and humor, he helped to elevate video to a legitimate art form, only to abandon it years later.

“He is the father of video art,” says Cristin Tierney, his gallerist of nine years. “Without him, nothing is the same. The work of Bill Viola, Gary Hill, Dara Birnbaum—it doesn’t exist in the way it does today without Peter. Maybe some do not think he is a household name, but every artist I have ever met knows who he is.”

In any event, he might become a household name soon. This week, four presentations of Campus’s work open across New York.

The biggest of the bunch, a retrospective called “peter campus: video ergo sum,” debuts at the Bronx Museum on Wednesday after stints in Paris and Seville. Meanwhile, Tierney will open “shinnecock bay,” an exhibition of two recent videos by the artist, at her Bowery gallery while showcasing other works at her Armory Show booth. Finally, Campus’s landmark 1976 single-channel video, Head of a Sad Young Woman, will play every evening from 11:57 p.m. to midnight on the billboards of Times Square as part of its public art program, until March 31.

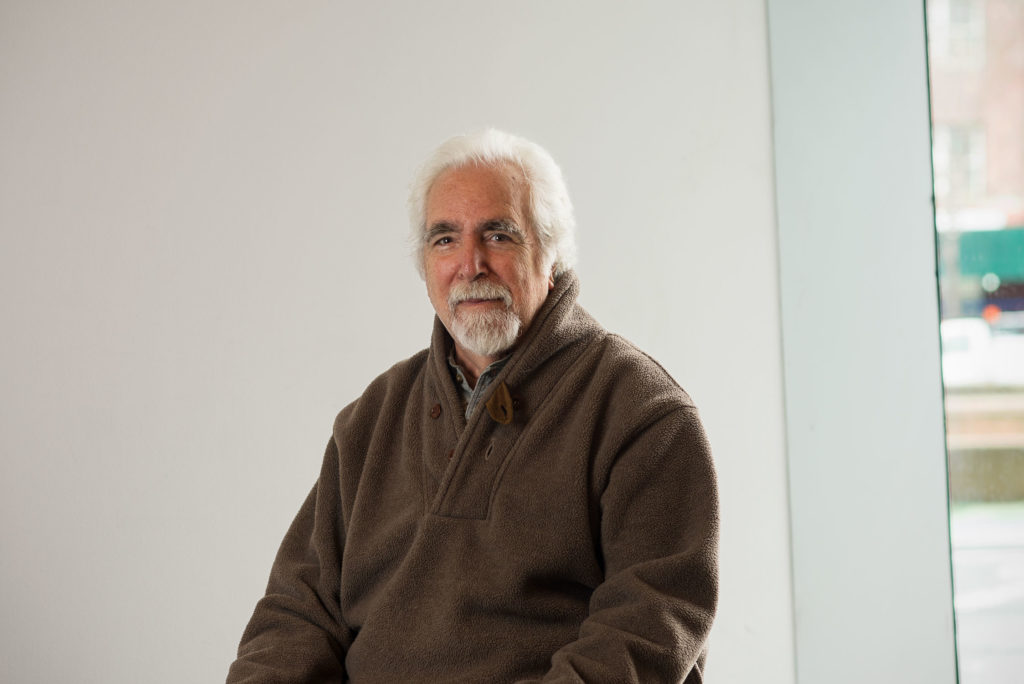

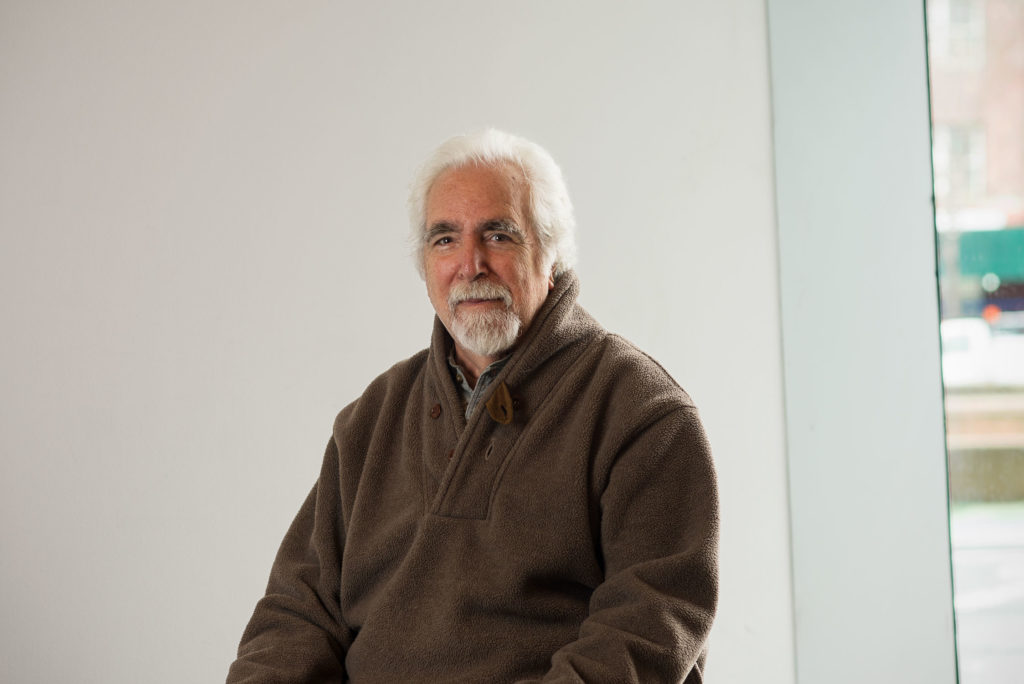

Campus, now 82, is not bothered by the renewed interest in his work. Nor is he particularly interested in this article.

“I’m more interested in art than I am in artists,” he says in his soft-spoken, measured voice. We’re sitting in the lobby of the Bronx Museum, where he’s in the throes of installation—a laborious process for any artist, but especially for Campus, whose work relies on increasingly outmoded technology. “I think there’s too much emphasis on artists these days.”

“Why do you think your work is of particular interest to people now?” I ask him.

“I have no idea.”

“It sounds like you’re not concerned with that question.”

“I’m not.”

Video still from peter campus’s Third Tape (1976). Courtesy of Cristin Tierney.

Campus was born in New York in 1937. His father was a first-generation American who grew up poor, became a doctor, and never really understood why his son wanted to pursue a career in art. His Ukrainian mother was a card-carrying communist—the effects of which Campus still seems to be coming to terms with. (He’s only started openly discussing it in the last two or three years.) She died when he was seven.

Today, Campus—who prefers his name be written in all lower-case letters—doesn’t consider himself a communist, but he’s certainly not a staunch capitalist either. When asked why he writes his name this way, he jokes knowingly, “I don’t like capitalization. Why should nouns be privileged?”

Campus began painting at age 13, often skipping class to spend time in the art room. “Art just totally enveloped me,” he recalls. He attended Ohio State University in the late ’50s, earning a degree in experimental psychology—a field that would come to influence his art. After a stint in the army, he moved back to New York and attended the City College Film Institute, eventually working on documentaries for nearly a decade.

In 1970, he purchased his first video equipment. At the time, video technology was new and quite distinct from the tools that had dominated the film industry for decades. “I just wanted to do something that looked very different from film and had very different rules,” Campus explains. “Video was so different. I was terribly interested in it at a deep level. I still can’t explain why.”

peter campus with his installation Optical Sockets (1973). Courtesy of Cristin Tierney.

In 1973, Campus was invited to create a series of works for the New Television Workshop, a newly formed organization at the WGBH-TV station in Boston that supported experimental televisual art. Using the station’s studio, he made what would become one of his most famous works and a pillar of 20th-century video art: Three Transitions.

The work featured the artist performing playful experiments in front of the camera, exploiting the then-nascent technology to wry, ironic ends. In the second “transition,” for instance, an expressionless Campus peers back at the viewer, rubbing blue paint on his face. But we don’t see the paint. Instead, he uses the chroma-key technique (reminiscent of a green screen) to overlay video of his face. It appears, then, as if Campus is erasing his face to reveal yet another face.

Today, Campus doesn’t love this work, the same way a journeyman musician doesn’t love the one radio hit he made early in his career. Yet Three Transitions is notable both for its art-historical resonance and its embodiment of Campus’s deep drive to use technology to examine the machinery in his own mind.

“I first saw Three Transitions as an undergrad and it had a profound effect on me,” Tierney recalls. “I loved the formalism of it, how its form and content were inseparable from one another, I loved its deadpan humor, and the way it seemed—aesthetically—to so perfectly encapsulate and represent a moment in art history.”

By that time, things were moving quickly for Campus. He had his first solo museum exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art in 1974—less than four years after he started making video art. In the five years that followed, the artist would go on to produce some of his best-known works, including Kiva (1971), an installation in which a live video feed, interrupted by a swinging mirror, documents gallery-goers, and Third Tape (1976), a video recording of an actor’s disjointed face shot through stacked mirror shards.

“Campus’s work is very much tied to the different movements developing in the ’70s, be it conceptual, minimal, or performance,” Anne-Marie Duguet, the curator of “video ergo sum,” tells artnet News.

peter campus, Kiva (1971). Courtesy of Cristin Tierney.

Campus took a sharp turn in 1979. Just as video was beginning to take root in the broader culture, he left the medium behind. He also left Manhattan, where he had lived for the majority of his life, and moved to Long Island to begin what he thinks of now as the second half of his career.

In a Thoreauian way, he became increasingly interested in nature, taking long, silent hikes.

“It was rejuvenating,” he recalls. “I was feeling pretty low at the time, emotionally. But nature was so healing. I tried to express it in my art, but it’s still amazing for me to stand there and see those colors and the gestalt of the place.”

Within a couple years, he began taking photographs of nature—a stark departure from the work on which he had built his name. Instead of mining technology in the studio to look inward, Campus began looking outward at the landscape.

By the mid-’90s, however, he seemed to have split the difference: He returned to video and has continued working in the medium ever since, making what he calls “videographs”—moving-image depictions of landscapes, digitally altered to move in and out of abstraction.

peter campus, locks eddy (2018). Courtesy of Cristin Tierney.

In the Bronx Museum lobby, chewing on the second-half of a croissant his wife saved for him, Campus says, “At the beginning of classes, I used to say to my students, ‘What kind of art would you make if it didn’t have your name on it? Would you make different kind of art?’”

For his part, Campus seems to have always made exactly the kind of art he wanted to make. His name, the recognition, this article—it’s all an afterthought.

Yet those around him are keenly aware of his broader influence and shifting position in the canon. “Peter’s work resonates today because he essentially predicted the future,” Tierney says. “We live on screens today. We connect with people via these screens and through constantly mediated, constructed and reconstructed images of ourselves and others. It is easy to see this in 2019, but Peter he knew it as early as 1971.”

She continues: “The title of Peter’s museum show says it all actually: ‘video ergo sum.’ I video, therefore I am. He’s known all along.”