On View

Two Visionary Women Photographers Collide in Unexpected Museum Showcase

Working a century apart, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron bent the medium of photography to their will.

Working a century apart, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron bent the medium of photography to their will.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The work of photographer Francesca Woodman is having a moment, being the subject of both an exhibition at Gagosian in New York and a must-see museum show at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though her name is reaching new heights of world renown, the young New York photographer has been a critical darling for decades and her works, produced before her tragically early death in 1981 at the age of just 22, have an enduring sense of style and experimental daring.

This timeless appeal is inevitably foregrounded throughout the impressively original London exhibition, which weaves her works with those of another celebrated historical photographer active a whole century earlier, Julia Margaret Cameron. A careful curatorial eye brings to the fore striking comparisons in which a similar subject matter is approached with mastery, mystery, and invention by the artist, while still very much bearing the essence of their respective eras. Each of these unique talents could, of course, have easily merited an exhibition of their own, yet this pairing does not constrain them.

Born in Calcutta in 1815, Cameron enjoyed a privileged Victorian upbringing due to her father’s involvement with the colonial East India Company. She and her sisters were known to be outspoken and unconventional, but it wasn’t until Cameron moved to London with her husband in 1845 that she became a member of artistic circles.

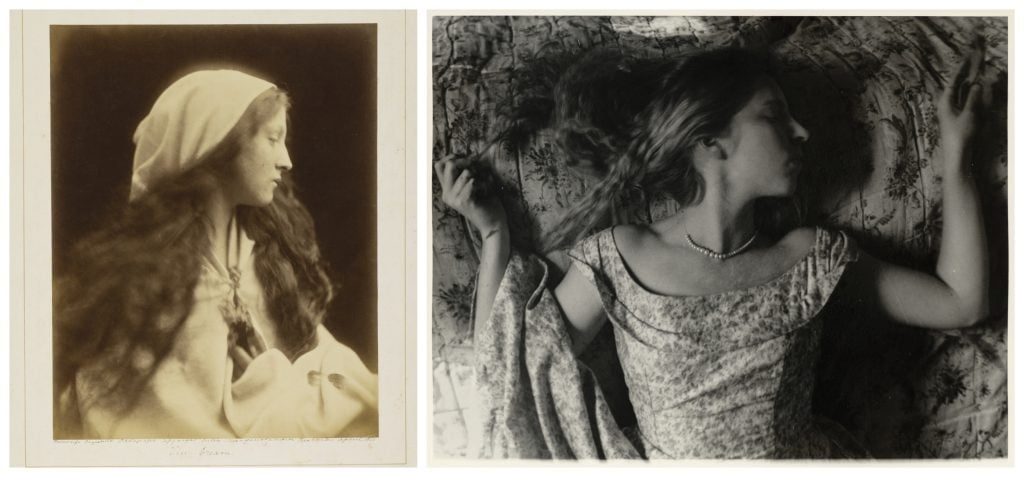

From left to right: Julia Margaret Cameron, The Dream (Mary Hillier) (1869). Courtesy of the Wilson Centre for Photography. Francesca Woodman, Untitled (1979). Courtesy of the Woodman Family Foundation, © Woodman Family Foundation/DACS London.

Cameron learned about the invention of photography in 1839, while still in her twenties, and first saw a daguerreotype in 1842. Yet she didn’t take up the practice herself until the age of 48, having been given a camera as a present by her daughter. In the last 12 years of Cameron’s life, until her death in 1879, she produced some 900 photographs that evince a highly exploratory approach to the fledgling art form.

Fast forward 100 years and photography had exploded in popularity, replacing writing as the most ubiquitous means of documenting of daily life. Like Cameron, Woodman received her first camera as a gift from her father. She trained formally at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with stints spent in Rome before moving to New York in 1979 to make it as a photographer. Woodman was highly ambitious and quickly became devastated by what she perceived as a lack of immediate success.

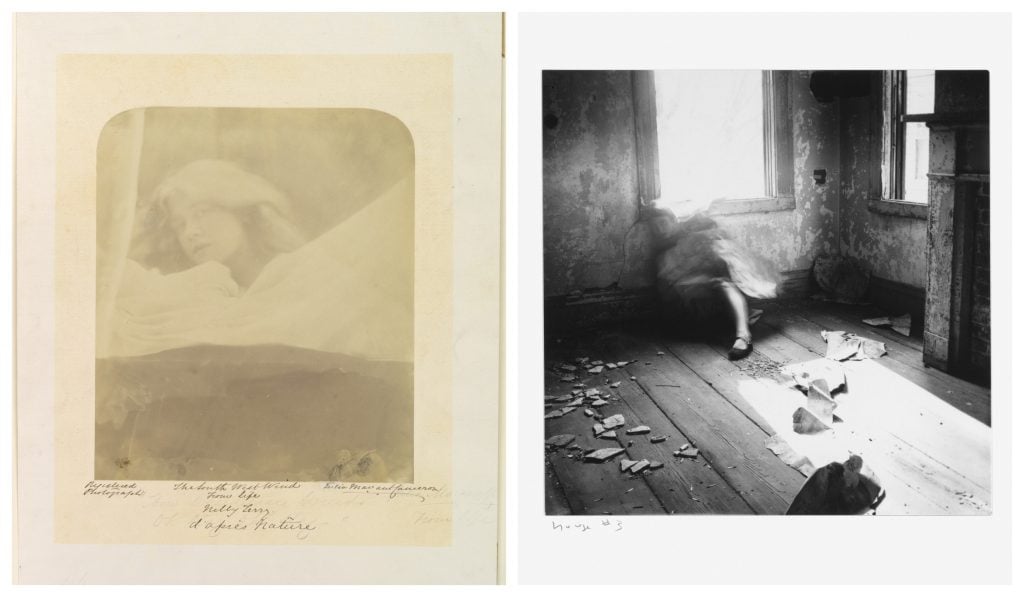

From left to right: Julia Margaret Cameron, The South West Wind (1864). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Francesca Woodman, House #3 (1976).Courtesy of the Woodman Family Foundation, © Woodman Family Foundation/DACS London.

The works of both photographers are roughly grouped according to themes of portraiture, otherworldly or dreamlike states, classical references, mythology, and the natural world, all of which reveal interesting affinities and departures in terms of staging, costume, focus, and style. Each artist has such clarity of vision that any differences in what could be achieved technically in their respective centuries feel mostly irrelevant.

Illusionistic effects that push photography beyond the status of a mere record are employed by both, as in the ghostly apparitions that haunt Cameron’s The South West Wind (1864) and Woodman’s House #3 (1976). Both artists seemed to have an instinct for capturing a partial truth and letting ambiguity and the viewer’s imagination fill in the bigger picture.

From left to right: Julia Margaret Cameron, I Wait (Rachel Gurney) (1872). Photo: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Francesca Woodman, Untitled from the “Angels” series (1977). Courtesy of the Woodman Family Foundation, © Woodman Family Foundation/DACS London.

Cameron often photographed close friends and family while Woodman, with a more modern notion of the artist available to her, usually made art using her own body. Either way, each took as a subject what was immediately available to her but imbued it with greater resonance, playing with fantastical elements or mythological allegories. In one nearly supernatural Untitled work from Woodman’s “Angel” series, the artist could almost be said to levitate.

As the National Portrait Gallery’s wall texts point out, angels have long been seen as able “to move between spiritual and earthly realms, the conscious and unconscious, and are often encountered in dreams or visions.”

Cameron’s great-niece Rachel was once instructed to adopt poses inspired by the putti from Renaissance paintings. She later called having “a pair of heavy swan’s wings fastened to her narrow shoulders[…] No wonder those old photographs of us, leaning over imaginary ramparts of heaven, look anxious and wistful. This is how we felt, for we never knew what Aunt Julia was going to do next.”

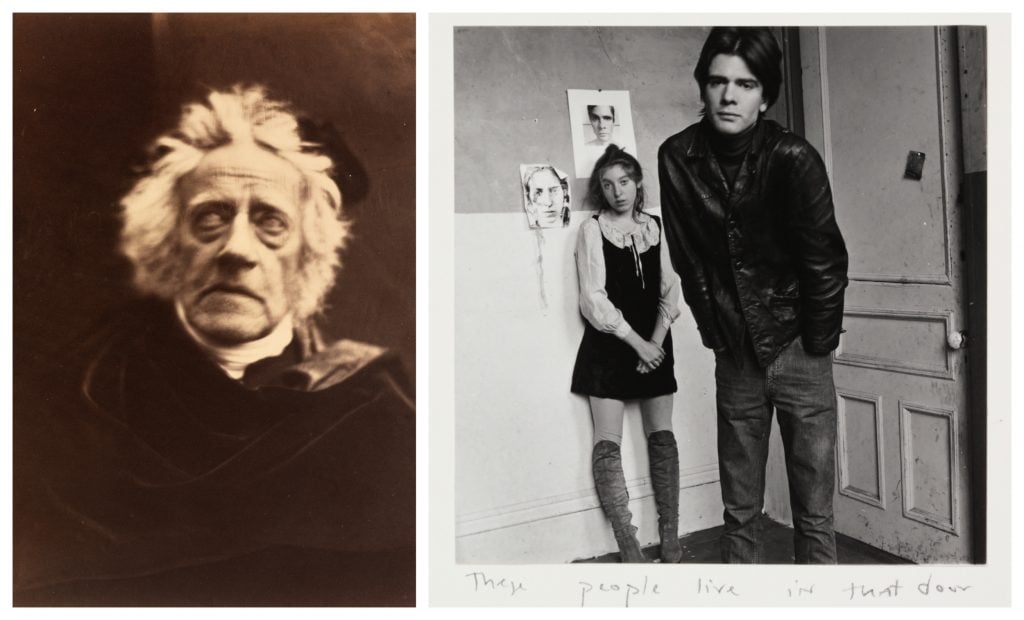

From left to right: Julia Margaret Cameron, The Astronomer (Sir John Frederick William Herschel) (1867). Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, R.I. Francesca Woodman, These People Live in That Door (1976-77). Courtesy of the Woodman Family Foundation, © Woodman Family Foundation/DACS London.

Sometimes, both Cameron and Woodman made straightforward portraits of the people in their lives. Woodman’s close friend Sloan Rankin and a one-time boyfriend, Benjamin Moore, appear in many photographs from the late 1970s. Alongside fond Pre-Raphaelite studies of muses and friends like Julia Jackson, Cameron turned her lens on some of the most important luminaries of her age like the scientist Charles Darwin, astronomer John Frederick William Herschel, the poet Alfred Tennyson, and the writer William Michael Rossetti. These animated character studies feel astonishingly ahead of their time.

Thinking back on the many double-act shows that had more ambition than bite, rarely does this curatorial conceit deserve to be as self-satisfied as here. How can a kinship be found in the oeuvres of two artists who evolved from such starkly different contexts? Rather than getting too caught up in a specific time or place—Victorian-era London or 1970s New York—the comparison pushes us instead towards more expansive interpretations that show already well-defined practices in a new light.

“Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In” is on view at the National Portrait Gallery in London until June 16, 2024.