Although an essential member of the Berlin Dadaists, German artist Hannah Höch was not recognized as such at the time.

She was born November 1, 1889, and passed away May 31, 1978, just when the cut-up aesthetic of punk was on the rise.

Overshadowed and undervalued by her male contemporaries, Höch’s genius took time to be noticed. Brian Dillon, in his Guardian review of Höch’s 2014 exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, wrote that in 1965 Hans Richter called her “a good girl,” one with a “slightly nun-like grace.” In his review for the Telegraph, Mark Hudson recounts Richter’s statement on Höch’s contribution to the movement: “sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money.”

The veiled misogyny extended to those whom she considered friends: artists George Grosz and John Heartfield disapproved of her inclusion in the Dada Fair in 1920.

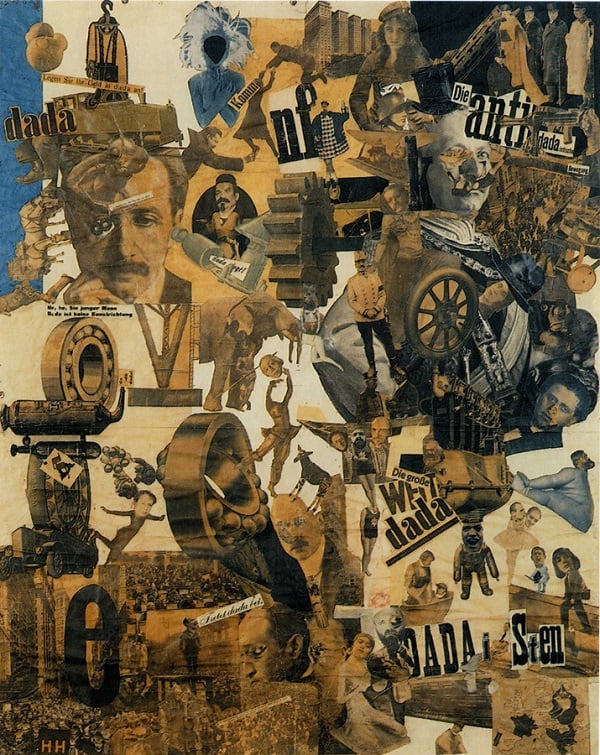

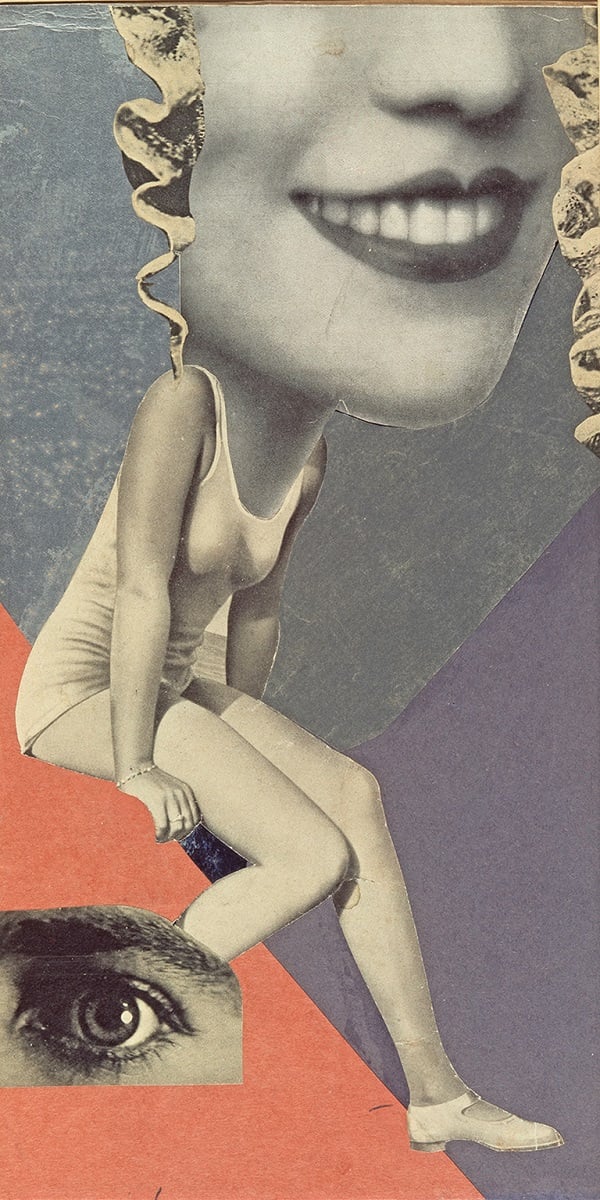

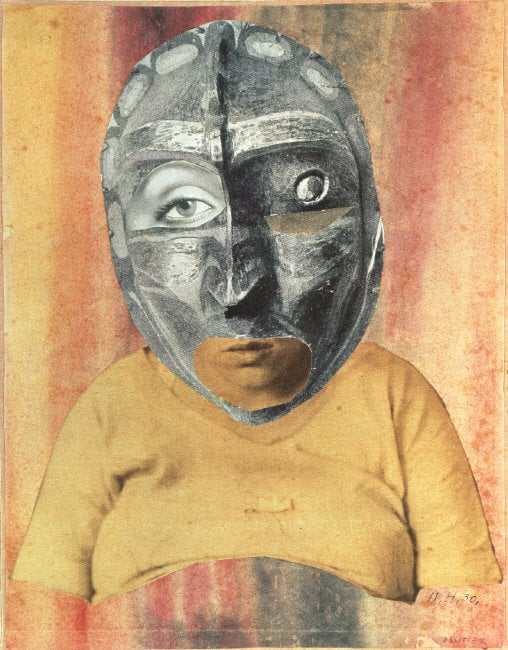

Yet her captivating collages spoke volumes about changing gender roles in the early decades of the last century and the media’s response to this “New Woman.” Höch developed her technique of photomontage with then-partner Raoul Hausmann, constructing compositions out of layers of found images and text in uninhibited Dada fashion. Her pieces critiqued society’s attitudes toward women, as well as clichéd representations of femininity.

On what would be her 126th birthday, we celebrate a woman who defied all that opposed her allowance into the canon of great Modern artists. See below for quotes from the artist as she speaks about the difficulties of making work as a woman, embroidery as an art form, and evading the Nazis as a “cultural Bolshevist.”

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands) (1919-1920). Image: © 2006 Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, © 2006 Hannah Höch / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo: Jörg P. Anders, Berlin.

On self-actualization:

“I wish to blur the firm boundaries which we self-certain people tend to delineate around all we can achieve,” Höch is quoted as stating in Dietmar Elger’s book, Dadaism.

In a Thought Catalog essay, Nicole Rudnick explains that Höch “rejected adult-world conformity in favor of youthful nonsense offered a means of circumventing the strict and serious rules that govern thought, language, and meaning” as the only female member of the Berlin Dadaists.

Hannah Höch, Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party) (1936). Image: Collection of IFA, Stuttgart, courtesy of Art Fund.

On misogyny in the art world:

“They continued for a long time to look on us women artists as charming and gifted amateurs, denying us any real professional status. Thirty years ago it wasn’t easy for a woman to impose herself as a modern artist in Germany,” she wrote.

Some of Höch male contemporaries saw her as an inferior artist. She endured by proceeding to make work and exhibiting, despite their sharp and petty criticisms.

Hannah Höch, Mother (1925–6). Image: © 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo credit: CNAC/MNAM/Dist Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY.

On the textile arts:

Trained at the Berlin School of Applied Arts, Höch learned techniques of embroidery and appliquè which she used in her photomontages. An excerpt of her “polemic on the potential of embroidery” includes this provocative quote about its relationship to culture was published in a 2014 issue of Selvedge.

“Embroidery is very closely related to painting. It is constantly changing, with every new style each epoch brings. It is an art and ought to be treated like one, even if thousands upon thousands of sweet female hands—displaying scant skill, no taste or color sense, and not a hint of inspiration—mis’handle quantities of good materials as foolishly as possible and call the results ’embroidery.'”

Hannah Höch, Kleine Sonne (Little Sun) (1969). Image: Landesbank Berlin AG, courtesy Whitechapel Gallery.

On stroking the male ego:

“Poor Raoul,” said Höch. “He needed constant encouragement to carry out his ideas and achieve anything at all lasting. If I hadn’t devoted so much of my time to looking after him I might have achieved more myself.”

On hiding from the Nazis:

“I had to disappear as completely as if I lived underground,” Höch wrote in her diary. After the Nazis labeled her a maker of “degenerate art,” Höch was forced to live under their radar in Berlin. After the city is liberated, she writes, “In my soul there is a calmness, such as I haven’t felt for many years.”