Art & Exhibitions

The Worst Art of 2024: 9 Standouts We Wish We Hadn’t Seen

There were more than a few howlers this year.

2024 was an “on” year for biennials and the calendar was packed with blockbuster shows and market events that took the Artnet News team across the globe. Yet despite the relentless marketing machines surrounding auctions and art fairs, the vibes often felt like the bookend to a decade of market ebullience.

Yet amid the market’s doom and gloom, however, we witnessed a refreshing shift: people are reconnecting with art’s intrinsic value and feeling less afraid to share their opinions. As we close out the year, we’ve rounded up the artworks that left us unimpressed—pieces that didn’t live up to the hype, ideas that fell flat, or works misplaced in their context. Art is subjective, of course, and disagreement is part of the fun. Whether or not you agree with us, we hope this inspires you to keep thinking critically—and to share your own thoughts about the art that moved you (or didn’t) this year.

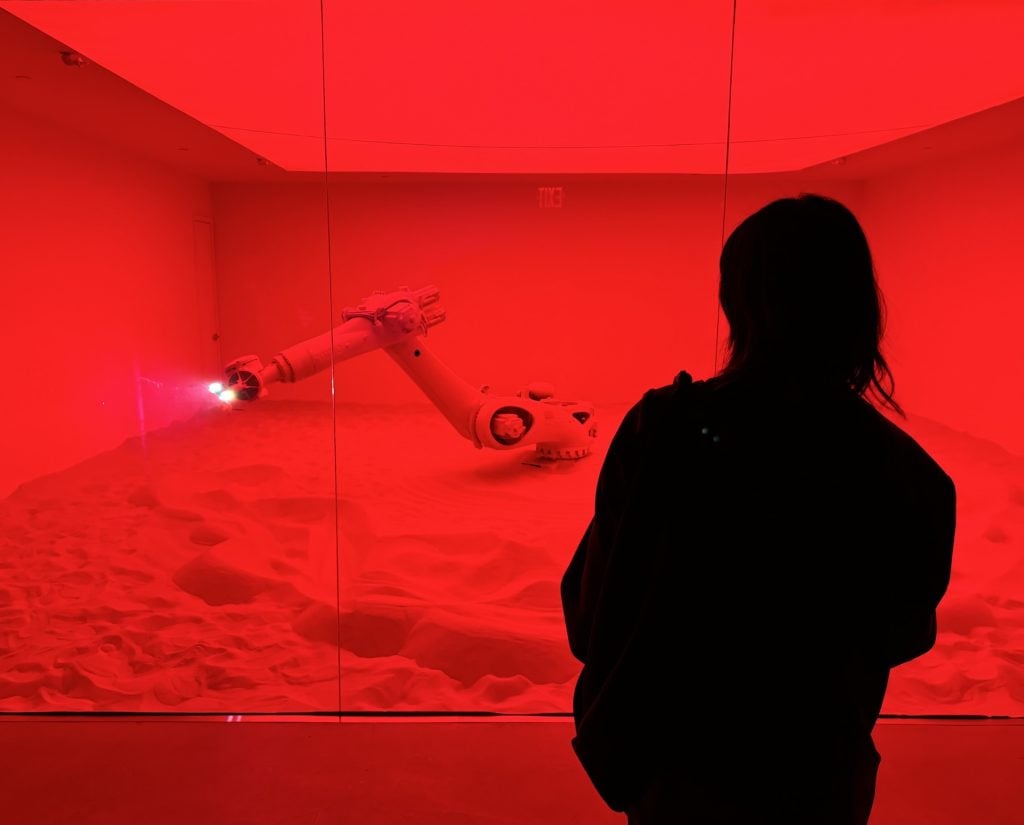

“Dark Matter,” at Mercer Labs, New York

A visitor contemplates one of the exhibits in “Dark Matter” at Mercer Labs. Photo by Ben Davis.

Mercer Labs opened this year, a $36-million immersive art complex across the street from the Oculus in FiDi, advertised (somewhat misleadingly) as a “Museum of Art and Technology,” the brainchild of artist Roy Nachum and real estate developer Michael Cayre. Its glowing pneumatic tube installation was probably all over your feeds.

And its haunted-house themed “Dark Matter” installation has its delicious moments, though it’s about as frightening as a bag of special-edition Black Garlic Doritos for Halloween.

What irritates me about it is that, after being billed as an “artist-designed” attraction, it sure is brazen about how it harvests ideas from popular artists or from other, often better immersive attractions (as a good number of its online reviews note). You can practically feel the investors saying “where’s the ball pit?” “Where’s the mirror room?” “More blinky lights!” the whole way through.

The result is that the impression Mercer Labs left me with was exactly like one of those made-for-Netflix movies like The Gray Man or Red Notice or Damsel, which feel as if they are just made up by an algorithm mashing together tropes people already like into a bland and safe movie-like thing.

Those movies are very popular, and Mercer Labs is as well. But like those films, I can’t imagine many people wanting to take this ride twice. And compared to a Netflix subscription, it’s not cheap—tickets are a staggering $50 a pop.

—Ben Davis

Claire Fontaine, siamo con voi nella notte, at the Holy See Pavilion, Venice

Installation view of Claire Fontaine piece at Pavilion of the Holy See, 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, With my eyes. Photo by Marco Cremascoli.

In 2024, socially engaged art retained focus in the art world, often revealing contraditions between intention and context. See: the irony of two works by artist duo Claire Fontaine shown at the Venice Biennale.

Claire Fontaine’s series “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere” served up a thematic anchor for Adriano Pedrosa’s historically inclusive exhibition, lending its title and visual framing to the show. Yet, errors in the translation of the neon text works to multiple languages added a layer of unintended self-reflection, turning the work’s—and by extension the biennale’s—critique of alienation and dislocation back on itself. Turns out, even a message about universal foreignness can become foreign to itself.

The work I’m nominating as the worst artwork I saw in 2024 embodied a similar misfiring. On view in the Vatican Pavilion at the Giudecca women’s prison, a 35-foot-long neon installation bore the poetic message in Italian: Siamo con voi nella notte (“We are with you in the night”). This work, its message inspired by 1970s graffiti expressing solidarity with political prisoners, became an apt microcosm of the Holy See’s misplaced ambitions. Despite its comforting words, the work actually caused discomfort for the prison residents, who lack the privilege of curtains. During my visit, I saw makeshift barriers—clothing hung in windows—to block out intruding light.

For the pavilion to foist such “socially engaged” contemporary art—intended first to be viewed by the intellectual, cosmopolitan audiences of the biennale—onto a prison setting, where freedom is already constrained, felt inappropriate and a poor substitute for meaningful social engagement. In contrast, Mark Bradford’s eight-year commitment to the same prison community in Venice as part of his Process Colletivo exemplified an alternate model for social practice art. Bradford’s work goes beyond fleeting gestures, offering dialogue and tangible development opportunities for the community. Next to this, the glaring neon message felt more like a signpost for the critical need for art in sensitive spaces to listen, adapt, and respond rather than dictate. Whether such engaged art can still work out how to be aesthetic along the way remains to be seen.

—Naomi Rea

Ai-Da, A.I. God, at Sotheby’s, New York

Ai-Da, A.I. God (2024). Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

Last month, a portrait of Alan Turing (the image on the right of the above triptych A.I. God) sold at Sotheby’s for $1.08 million. It was billed as the first artwork created by a humanoid robot to head to auction. Everyone in the art world is pretty sick of hearing about Ai-Da at this point, but for anyone who doesn’t yet know, she is trained to paint using cameras in her eyes that relay information to an A.I. algorithm, which in turn operates two robotic arms. Beyond this surface-level explanation, not much more has been revealed about Ai-Da’s processes, apart from the fact that she works with human assistants… casting some doubt on what exactly we are looking at when we look at the works she has apparently authored.

Created by the Oxford gallerist Aidan Meller and a team of university researchers, Ai-Da was first debuted in 2019 with a suspiciously glamorous appearance that gave “sex doll.” This has since been toned down, with her luscious locks chopped into a severe bob and her frilly, pastel outfits swapped out for denim overalls, presumably so she can hope to be taken more seriously. Sadly, as humanoid robots go, Ai-Da simply isn’t very good. When she was invited to address the U.K.’s House of Lords in 2022, she sputtered out a few pre-prepared answers before shutting down and requiring a reboot. In an age of advanced generative A.I. tools like ChatGPT, is this really going to cut it?

The reason I most take issue with Ai-Da’s portrait of Alan Turing, aside from the fact that it looks like it might hang on the wall of a particularly cursed Airbnb, is that this gimmick is a science project masquerading as art. With the Sotheby’s sale grabbing so many headlines, it’s little wonder people still assume all “A.I. art” is ugly pastiche that lacks any serious creative intent. The victims here are the many artists who have integrated A.I. into a pre-existing, considered practice and are far more deserving of public interest. If intelligent robots are your thing, then I highly suggest you check out the lyrical paintings produced by Sougwen Chung and their collaborator D.O.U.G.

Anyway, according to the Sotheby’s specialists, Ai-Da’s “fractured visual style, similar to Käthe Kollwitz and Edvard Munch, rejects pure representation, opting instead for a reflection of the technological and psychological fractures that characterize modern life.” Does any of that ring true to you?

—Jo Lawson-Tancred

Maurizio Cattelan Comedian (2019)

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian sold for $6.2 million at Sotheby’s New York. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

I have long liked and admired Maurizio Cattelan’s cheeky and playful artworks, especially those that riff on the art world, and his memorable takeover of the Guggenheim Museum in 2011, with “Maurizio Cattelan: All.”

However even from the first mention of Comedian, the duct-taped to the wall banana that became a global sensation after the 2019 debut at Art Basel Miami Beach, I just never got on board with it as anything more than a short-lived art world practical joke.

I was unimpressed when I learned that Sotheby’s was giving it a second life—offering one from the edition at the recent New York November sale with an asking price of $1 million (that’s roughly ten times the initial $120,000 asking price), and maybe one of the few who was even more stunned to see the final $6.2 million result.

I was touring the auction house preview before the sale and couldn’t get over the fact that the particular banana taped up that day was already starting to rot as it sat in its own custom-built archway structure inside the Sotheby’s galleries. Nearby, hung gems from some of my favorites such as Ed Ruscha, and Dana Schutz, which felt downright disconcerting. You can talk to me all day about Dada, jokes about value, scandal, outrage and upending notions of contemporary art. I think the artwork is stupid, and a waste of energy.

—Eileen Kinsella

MSCHF, “Art 2” at Perrotin Los Angeles

Install imagery of MSCHF’s “Art 2” at Perrotin Los Angeles. Courtesy of Perrotin.

I’ll freely and gladly admit that some of MSCHF’s stunts have made me laugh over the years since the cartoonish red boots burst onto the scene (an object that made the 3D world embrace the superflat). I stepped into their show at Perrotin Los Angeles this past Spring, “ART 2” with my heart open to the collective becoming the new prankster artist to watch. However, I found their concept to be half-baked at best.

The show purported to showcase a “second act” but instead I thought it lazily pandered to the lowest common denominator of trollish Internet humor over advancing any conceptual practice at all. In all, the show felt more like a puckish sneaker design firm’s portfolio than art.

—Annie Armstrong

The New Alec Monopoly Mural on Rivington Street in New York

An Alec Monopoly mural on Rivington Street in New York. Photo by Andrew Russeth

I actually kind of admire Alec Monopoly in the way that one admires certain comic-book supervillains. We could all learn something from his brio, his confidence, his sheer love of life. That said, I would prefer not to look at his cartoons on a regular basis, and I do not think they should be in public space, where they can influence impressionable youths. (Kids: This is not art, not really.) Monopoly apparently painted this fantastical, strangely boring skyline in April, around the time that New York was hit with a very minor earthquake. (“Painting a Mural in NYC during an earthquake was crazy!” the artist wrote on Instagram.) It’s interesting to remember that the legendary Spiritual America gallery was located down the street in 1983-84. Neighborhoods change.

Lest this entry read as a cop out, here’s my runner-up for worst of the year: Lucy Bull’s solo exhibition at the ICA Miami, “The Garden of Forking Paths.” Bull makes perfectly fine paintings by slicing and dicing Pavel Tchelitchew, Marc Chagall, and various Surrealists, but the acclaim they have received is completely out of proportion with their achievement. (MOCA, LACMA, and the Hirshhorn hold examples, along with many deep-pocketed collectors. The ICA’s wall labels present a murderers’ row of lenders.) These are razzle-dazzle pictures, frequently overworked, and they insist on telling you over and over again how interesting they are, piling up special effects for your consumption. Fun for a moment, but fundamentally cheesy.

—Andrew Russeth

“Pierre Huyghe. Liminal” at Punto della Dogana, Venice

Pierre Huyghe, Liminal (temporary title) (2024–ongoing). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Marian Goodman Gallery, Hauser & Wirth, Esther Schipper, and TARO NASU. ©Pierre Huyghe, by SIAE 2023.

Contemporary art has a hard time competing with history in Venice. It’s easy to fall on your face while going against Titian and Tintoretto —or even simply showing the work along the same algae-hued canals. Projects that succeed tend to embrace La Serenissima’s history, architecture, and grandeur (be it minimal, conceptual, operatic or any other form).

Francois Pinault, who converted two historic spaces in Venice into contemporary art venues, should know about this. His Palazzo Grassi’s first exhibition is forever seared into my memory with its Jeff Koons’s hanging heart sculpture amidst Urs Fischer’s suspended rain over the column-lined atrium. It was pure visual magic.

This year, the French billionaire missed the mark, with both venues. I found Palazzo Grassi’s exhibition of Julie Mehretu anemic, formulaic, and dull. It felt like corporate art, with no difference in experience between one massive canvas and another. What did the work have to do with an elegant, mid-17th century Venetian palazzo? It could have been hanging in a hotel lobby or a windowless boardroom.

But at least it wasn’t offensive. That distinction belonged to Pierre Huyghe’s solo show at Pinault’s second venue, Punta della Dogana. Huyghe, who collaborated with independent curator Anne Stenne, transformed an iconic late-17th century Venetian customs complex (refurbished by Japanese architect Tadao Ando) into a dystopian fantasy. The setting felt like a giant crypt. The crescent windows overlooking Piazza San Marco all hidden in the darkness, with visitors stumbling around.

One moment you were startled by a masked figure clad in black, suddenly emerging from the shadows. Another, you faced a haunting film of a hybrid creature, part monkey, part little girl. Elsewhere, aquariums were swimming and crawling with godforsaken creatures. AI made an appearance too. The artist’s vision was gratuitously bleak. I met people who really liked the show. But what did it gain from being in that historic setting? I felt disappointed not to see any of it, and couldn’t leave the exhibition quickly enough. Sadly, I can’t unsee it.

—Katya Kazakina

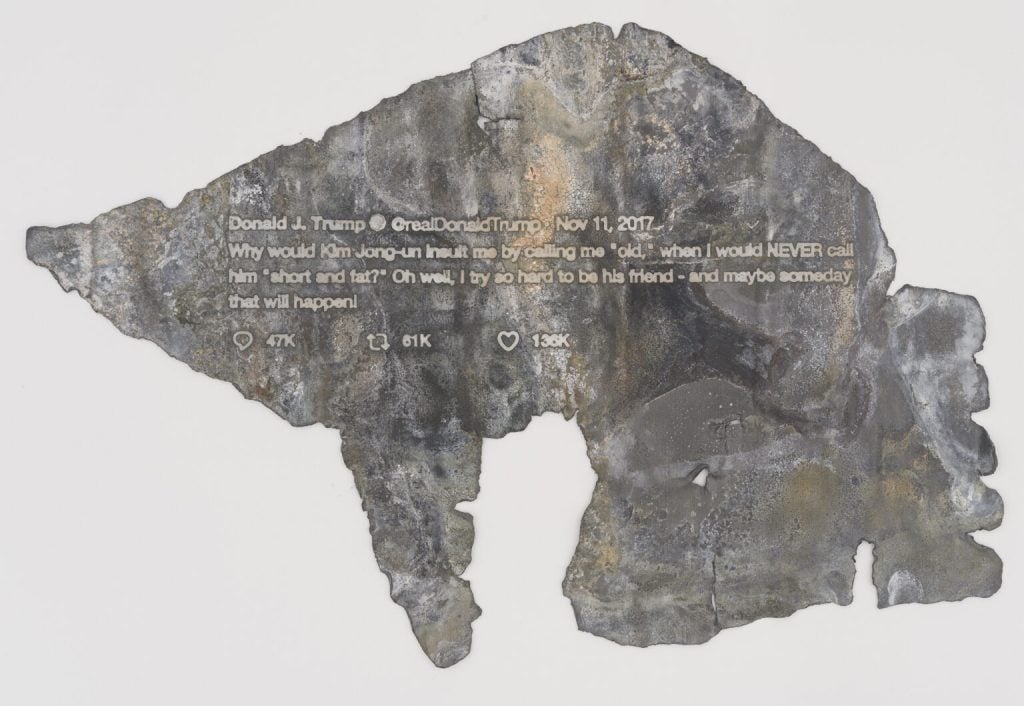

Jenny Holzer, Cursed (2022) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Jenny Holzer, Cursed (2022), detail of one of 296 elements. Text: Tweets by former President Donald Trump. Photo ©2022 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Jenny Holzer is one of the few artists of her generation who I feel confident will remain in art history books for generations to come, having mastered transforming the written word into striking and memorable visuals. That’s why I was truly excited to see what she would do in her return to the famed rotunda of New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, where she had last exhibited in 1989. While the custom-built LED screen for Light Line, with overlapping messages spiraling up and down the six stories of the circular gallery on a six-hour loop, was impressive, that effort seemed to exhaust the artist, making the rest of the show seem like a complete afterthought.

But the piece that sticks with me in a bad way is Cursed, 296 paper-thin, fragments of lead tablets, each inscribed with a Tweet sent by Donald Trump, weathered and distressed. Holzer hung some pieces on the wall, then seemed to give up, leaving the vast majority in a trash-like heap on the museum floor. In the wake of his election to a second term, this piece feels particularly impotent to me. Why did Holzer validate the man’s existence, two years after he left office the first time, by spending time committing his inane social media ramblings into a lasting work of art?

With Trump’s second term looming on the horizon, I fervently hope there will be less art mocking and ridiculing him. It would seem that most of the general public takes him seriously. Let’s focus on trying to offset the potentially catastrophic effects of the policies Trump hopes to enact, rather than tracking every stupid move he makes with toothless outrage.

—Sarah Cascone

Banksy’s “Beastly London” Series, London

A cyclist passes by a new artwork by Banksy on an old billboard in Cricklewood. The artwork, depicting a wild cat, like a tiger or leopard, is the sixth new artwork in six days in London by the elusive street artist. Photo: Vuk Valcic/ SOPA Images/ LightRocket via Getty Images.

Banksy’s latest graffiti series across London made me realize that I feel the same way about his work as I feel about The Beatles: I can appreciate their early artistic contributions and love some work that has something to say, but their oeuvres are generally milquetoast. Let me describe some of the works in this series: a silhouette of a mountain goat on the side of a Kew Bridge home; two elephants leaning towards each other from two windows; a cat stretching on a decaying plywood billboard; three monkeys hanging from the side of a subway station in East London; a mural of a gorilla at the London Zoo lifting a gate to let other animals out, which was quickly removed; and a rhino mounting an abandoned car from behind. I think I drew some of these in middle school.

It’s wild to me that a man who has remained anonymous for decades, who was able to secretly make art in Ukraine as it was bombed by Russia, who made art of a migrant child on the side of a Venetian palace, who took a firm stance on Brexit, whose work has led to headline-making copyright and trademark disputes, who is among the highest-profile counterfeited artists in the world, could create something so, well, boring. And it’s a trend in his work that I’ve noticed over the last few years. Is his anonymity truly the only thing left interesting about him?

—Adam Schrader