Art World

9 of the Absolute Worst Artworks of 2018, as Chosen by the artnet News Staff

We encountered some real dippy flubs out there this year, from masterstrokes of vainglorious pretension to pervy stuff to some pure groaners.

We encountered some real dippy flubs out there this year, from masterstrokes of vainglorious pretension to pervy stuff to some pure groaners.

Artnet News

Sometimes we art professionals come across an artwork so profound, so thrilling, so old-fashionedly beautiful that it lingers fondly in the memory for years to come. Other times, we look at something and think, “Whoa… that stinks.” Like, big-time. For writers, this is like a gift from heaven, because you can’t really write funny, biting, acidulous prose about good art, and that’s fun. Here, read an array of artnet News’s usually happy-go-lucky staff vent about the floppiest duds of 2018.

A cutting review!

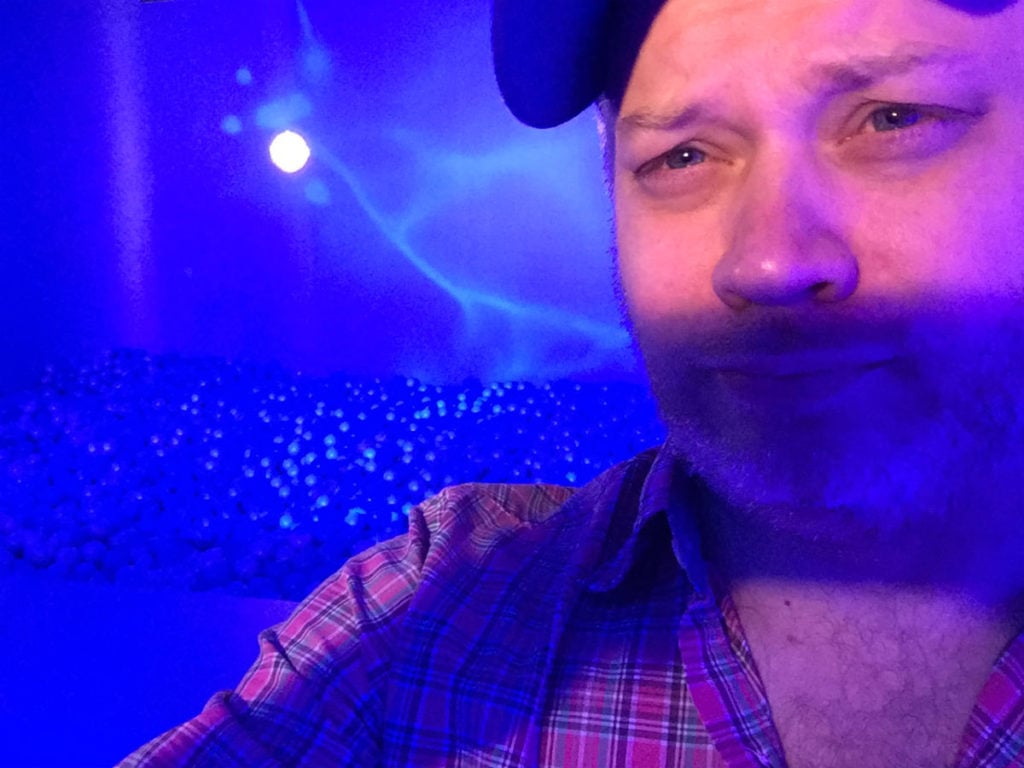

I already reviewed this limp Brooklyn-based attraction at midyear, so maybe I’m beating a dead horse—or a dead Instagram Trap, to be precise. (This October it was rebranded as Nightmare Machine, an Instagrammable haunted house). But just to be clear: it’s not that I just hate the Instagram environment trend that has sprung up everywhere. I took a spin through the Color Factory in SoHo and found it to be comparatively well done, even creative; in general, I’d go so far as to argue that we should do a better job at taking this craze seriously for what it represents socially. I just don’t think the Dream Machine itself took itself very seriously. It paid only the thinnest service to its own “dream” theme in favor of recycling a bunch of ideas that have already become cliches in other Instagram Trap environments (ball pits! mirror rooms! free candy!), serving as an Instgrammable reminder of just how cynical and tiresome this trend can, and will, get before the novelty exhausts itself.

—Ben Davis

I get it. I get it. It’s a conceptual work reflecting the artist’s belief that whatever he decided to do in the studio is “art.” I even tried to focus on the significance of his attempts to maintain the “contrapposto” pose associated with classical and Renaissance sculpture while navigating a long narrow corridor. I still can’t decide whether I was more overwhelmed with indifference or irritation or a headache-inducing mixture of both. It made my brain hit snooze. #SorryNotSorry.

—Eileen Kinsella

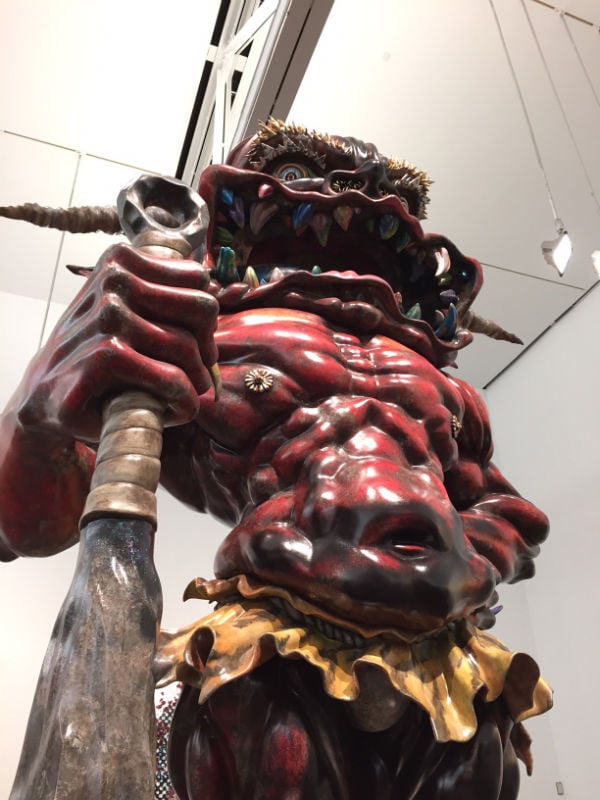

Takashi Murakami, Embodiment of A (2014). Photo: Ben Davis

This is quite simple. All you have to do is scroll up and take a look at this dinky behemoth by Takashi Murakami to see why it qualifies as one of the worst works we saw all year. Sure, it was a leap for the artist to go from his twee aesthetic to something so brazenly grotesque (as our very own Ben Davis has pointed out). But this lumbering beast is ten steps too far. It didn’t help that the enormous sculpture was surrounded at the Vancouver Art Gallery by colossal and wretched paintings of lumpy old men. Truly a grisly sight.

—Pac Pobric

At left, the 15th-century statue of Virgin Mary before being “restored” (right) by a local woman in Asturias, Spain. Photo DSF/AFP/Getty Images.

This year gave us not one but two spectacularly botched restorations in the vein of the legendary “Beast Jesus.” One was a 16th-century sculpture of Saint George in Navarre, Spain, that was repainted by a local art teacher to look like a character in a Pixar film. The other was a 15th-century wood carving of Mary, Saint Anne, and baby Jesus in Asturias, Spain, that a local antique-shop owner repainted in neon, making it look more like a lawn gnome than a sacred object. (Every single one of these calamities, for some reason, seems to happen in Spain.) Between the two, it was difficult to pick the best of the worst, but the shop owner’s DayGlo paint job on a wooden sculpture that never had any paint to begin with takes the cake. My favorite part was her matter-of-fact explanation: “I’m not a professional painter but I’ve always liked painting and the statues really needed painting,” she told El Comercio. “I painted them as best I could using what I thought were the right colors.”

I will add a caveat here, though: They say you shouldn’t judge art you haven’t seen firsthand, and I’ve only seen this in pictures. Maybe it looks much subtler in person.

—Julia Halperin

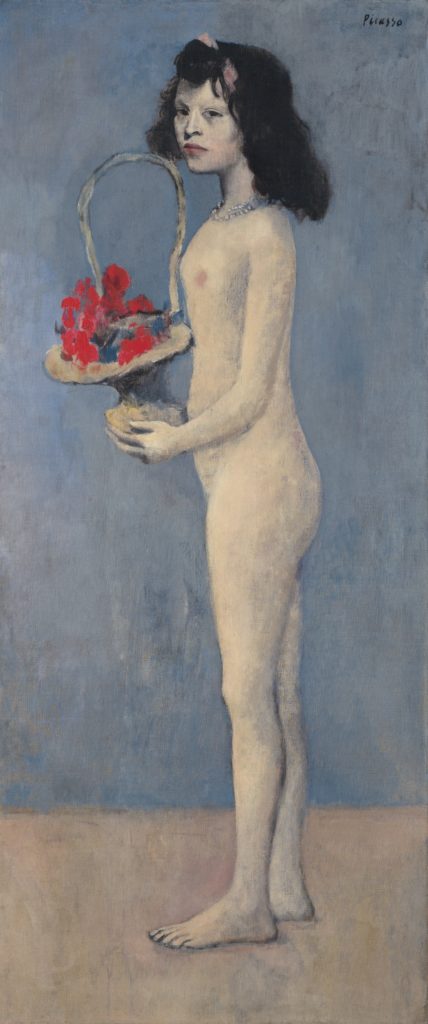

Pablo Picasso Fillette a la corbeille fleurie (1905). Photo: courtesy of Christie’s.

I’m cheating because I did not see this in real life, but I saw it a lot everywhere else. Picasso’s 1905 portrait of a barely pubescent and impoverished girl, standing naked to the side to showcase her small figure and apparent lack of breasts, grosses me out. Formally speaking, it isn’t bad art; Picasso is a virtuosic painter. But it leaves a bad taste in my mouth that this painting could sell for $115 million at Christie’s, which it did in May, with little or no mention of the troubling power relations that may have been at play between the so-called “Linda” (who was known to be a flower-seller and a child prostitute) and a 24-year-old Picasso. It’s 2018 (almost 2019!), and yet, in the market at least, the male gaze continues to be valorized through accumulation.

—Kate Brown

![??? ? ??? ? ?? [??? ? (?))] + ?? [???(? − ?(?(?)))], Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy. Courtesy Christie's Images Ltd.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2018/08/Edmond-De-Belamy_frame-and-picture-1024x768.jpg)

??? ? ??? ? ?? [??? ? (?))] + ?? [???(? − ?(?(?)))], Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

—Naomi Rea

![??? ? ??? ? ?? [??? ? (?))] + ?? [???(? − ?(?(?)))], Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy. Courtesy Christie's Images Ltd.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2018/08/Edmond-De-Belamy_frame-and-picture-1024x768.jpg)

??? ? ??? ? ?? [??? ? (?))] + ?? [???(? − ?(?(?)))], Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy. Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

There are many valid reasons to conclude that Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, misleadingly billed as “the first piece of AI-generated art to come to auction,” is the aesthetic equivalent of something a plumber normally has to be paid to snake out of a clogged toilet. But perhaps nothing encapsulates my disgust with the piece as cleanly as the difference between how Naomi and I have listed the work in the header versus the way Obvious convinced Christie’s to list it when the house sold the portrait this October.

As Naomi mentioned, the three members of Obvious contend that the (open-source, minimally tweaked) algorithm used to output the image should be credited as the “artist.” But accepting this idea means further advancing the single most dangerous and most prevalent misconception about artificial intelligence technology today. By definition, an algorithm is a set of instructions for the performance of a task. Instructions are written by humans—and, more to the point, specific humans with specific goals, tendencies, blind spots, and biases. No matter who deserves ultimate credit for the final algorithm Obvious used, Obvious bears total responsibility for the dataset it fed into the algorithm. And here, the group’s choices resulted in something painfully regressive: three young white guys literally teaching software that “art” means “portraits of older, aristocratic white people.” And worst of all, the legacy art world went bananas over it.

So it would have been bad enough that Portrait of Edmond de Belamy has all the conceptual rigor of three college freshmen who just smoked their first joint. (“Dude, imagine, like, fancy old portraits, except they’re made by a fuckin’ computer!“) Obvious made matters far worse by taking technology that could and should be used to usher in a better future and instead directing it hundreds of years into a past that we as a culture have at least begun to evolve beyond. But the art world at large brought this embarrassment to a crescendo by treating the work and the group behind it as the standard-bearers of an alleged new art form. The whole episode was like watching someone gain the power to teleport to other habitable planets, then get rich by selling tickets to a world where it isn’t illegal to hunt bald eagles yet. And for that, Portrait of Edmond de Belamy deserves to live in infamy.

—Tim Schneider

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World (1993). Photo by Sarah Cascone.

Perhaps it is unfair to judge a work of art based on the media circus that surrounds it, but when curators at the Guggenheim bowed to threats and agreed not to include live animals in Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World for the exhibition “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World,” that controversy inevitably became part and parcel of how audiences experienced the piece.

Theater of the World was supposed to include live animals—it was conceived as a caged sculpture full of live insects, amphibians, and reptiles. Throughout the show, nature was meant to run its course, some animals fighting, others serving as food. I’m certainly wholeheartedly against animal cruelty, but I remain unconvinced that the animals would have suffered any more than your average caged pet being fed live crickets and bugs.

But when PETA got wind of it, along with two other animal-related works meant to be in the show, they called for its removal from the exhibition, and a Change.org petition denouncing the artworks received over 800,000 signatures. The Guggenheim folded under the pressure, and the Theater of the World went on view without the animals.

By the time I saw the show in early January, shortly before it closed, all I could see in the work was an empty cage: a symbol of censorship, political correctness, and the reactionary nature of online outrage. It was an ugly reminder of the growing number of museum controversies, and the sense of entitlement I see in the more extreme advocates of trigger warnings. It’s not the artist’s fault, but when I think about Theater of the World, I think of the evils of censorship, and how they are threatening the art world on an increasing basis.

—Sarah Cascone

Surprised onlookers react as Banksy’s Girl With a Balloon self-destructs at Sotheby’s.

Let’s be clear, Banksy’s Girl With Balloon was a terrible artwork before it was shredded at Sotheby’s Contemporary Art sale in London in October. I didn’t think it was possible to make it worse. The thematic content was far too obvious, a young girl lets go of heart-shaped balloon. What could that metaphor possible represent? Then Banksy (or somebody else) shredded it in an evening sale just after it was hammered down for £1 million ($1.4 million) in a sensationalist publicity stunt, and the world went crazy. Sotheby’s insisted they knew nothing of the plans, but anyone with knowledge of art auctions knows that no specialist would send an artwork to the auction block at that price point without inspecting every inch of it first. The shredding itself was another all-to-obvious allusion to the commercialization of art. In the aftermath of the stunt Banksy said on social media that he had intended to shred the whole work but the shredder malfunctioned. If only it had worked.

—Henri Neuendorf

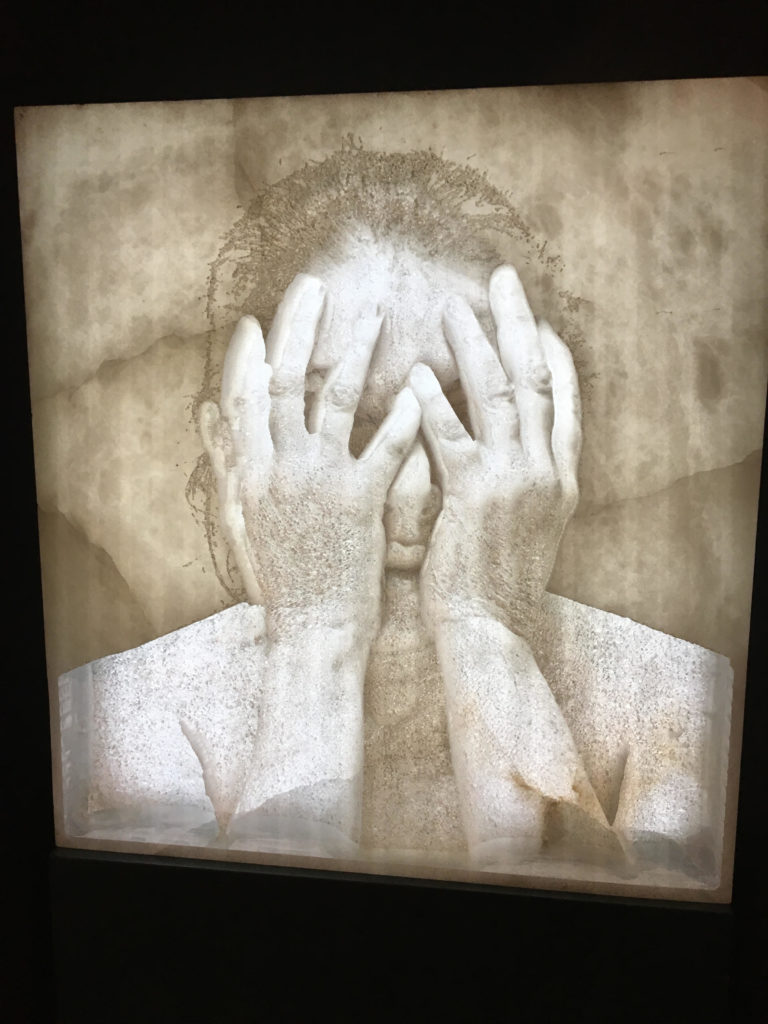

Marina Abramović, 5 Stages of Maya Dance (2018), at Masterpiece London.

Even the greatest durational artists have their off days, and it pains me to say that Marina Abramović’s over-the-top theatrical installation at the entrance of the Masterpiece London art fair this summer was the worst presentation I saw all year. Individually, the five alabaster relief self-portraits might have conveyed something of the artist’s charismatic presence. But as a spot-lit, walk-through experience in a darkened space, the Factum Arte/Lisson Gallery booth looked more Madame Tussauds than a work of art to be taken seriously. As a journey through her celebrity, 5 Stages of Maya Dance was Abramović’s Gloria Swanson moment: frozen, ready for her close-up, for eternity. It was Sunset Boulevard—and not in a good way.

—Javier Pes