Throughout the history of Western art, certain concepts have remained durable. Style. Iconography. Representation. Even when these categories are being inverted or rejected, they remain at the foundation of most discussions of European and American art. But as useful as these terms can be, they also box us in—especially when we’re talking about art from outside the Western canon. With Chinese art in particular, these categories, which have had such a sweeping influence, can prevent us from other productive ways of seeing.

“All the concepts we use to study Chinese art are derived from Western art history,” says Wu Hung, a professor at the University of Chicago and a prolific historian of Chinese art, who is currently delivering the A. W. Mellon Lectures at the National Gallery of Art. “In China, there were, of course, traditional discourses on art, even from as early as the ninth century. But they only dealt with calligraphy and painting. Sculpture and architecture were not considered art. So it was a very narrow art history.”

Throughout his talks, which are collectively titled “End as Beginning: Chinese Art and Dynastic Time,” Wu Hung is examining how Chinese art has historically been periodized, interpreted, and contextualized.

”In my talks, I deal with two kinds of materials, both of them historical,” he says. “One is the real object, the visual material. The other materials are historical writings, ritual prescriptions, mythologies.” The goal, he says, is to bring the two together to understand more fully the traditional purpose of an object, and the narrative it was originally meant to fit.

The below excerpt is adapted from Wu Hung’s first lecture, “The Emergence of Dynastic Time in Chinese Art,” which was delivered on March 31. His final three talks will be presented on April 28, May 5, and May 12.

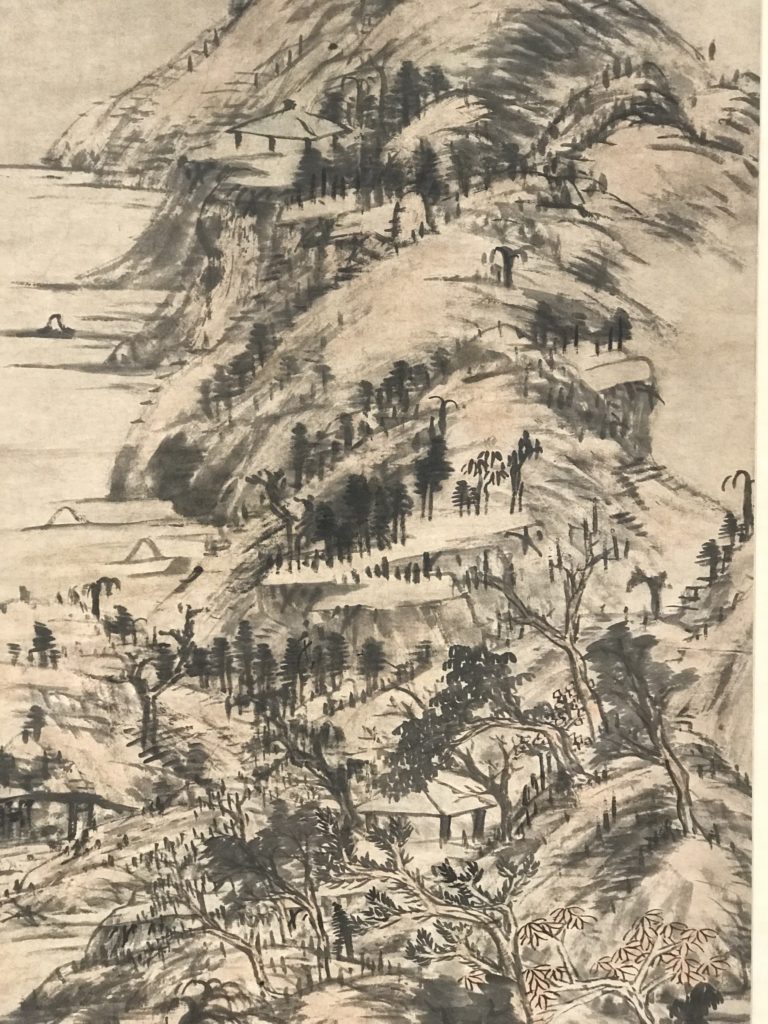

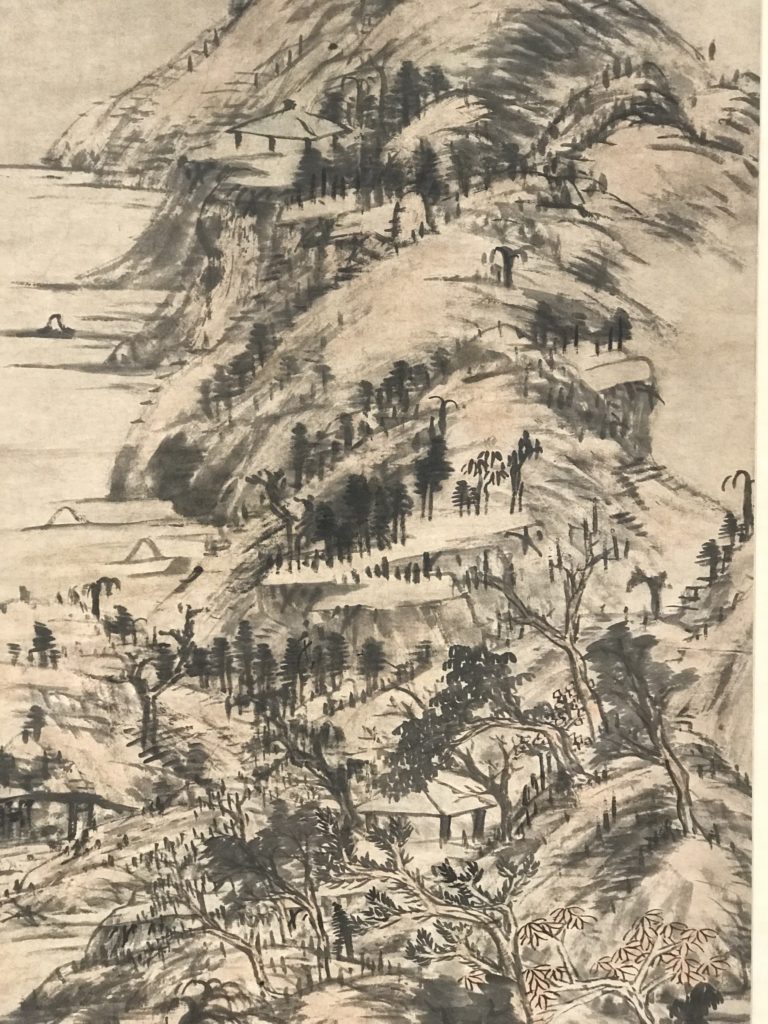

Zhu Da, Landscape (17th century). Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D. C. Photo: Wu Hung.

I want to first briefly explain the background of this lecture series. Last year I gave a talk at the College Art Association’s annual conference titled “Chinese Art History as Global Art History.” I told the audience that although China has a long tradition of art historical writing, producing the first comprehensive painting history as early as the 9th century, the modern field of Chinese art history, either in China or elsewhere, did not naturally grow out of this premodern scholarship. Instead it emerged as part of a sweeping global modernization movement in the 19th and 20th centuries, which reorganized local knowledge into supposedly “universal” systems of disciplines. The idea of art history as a “humanistic discipline” was introduced to China in the early 20th century, where it gave birth to a new kind of art-historical writing that instantly de-legitimized the old-fashioned literati discourse on art.

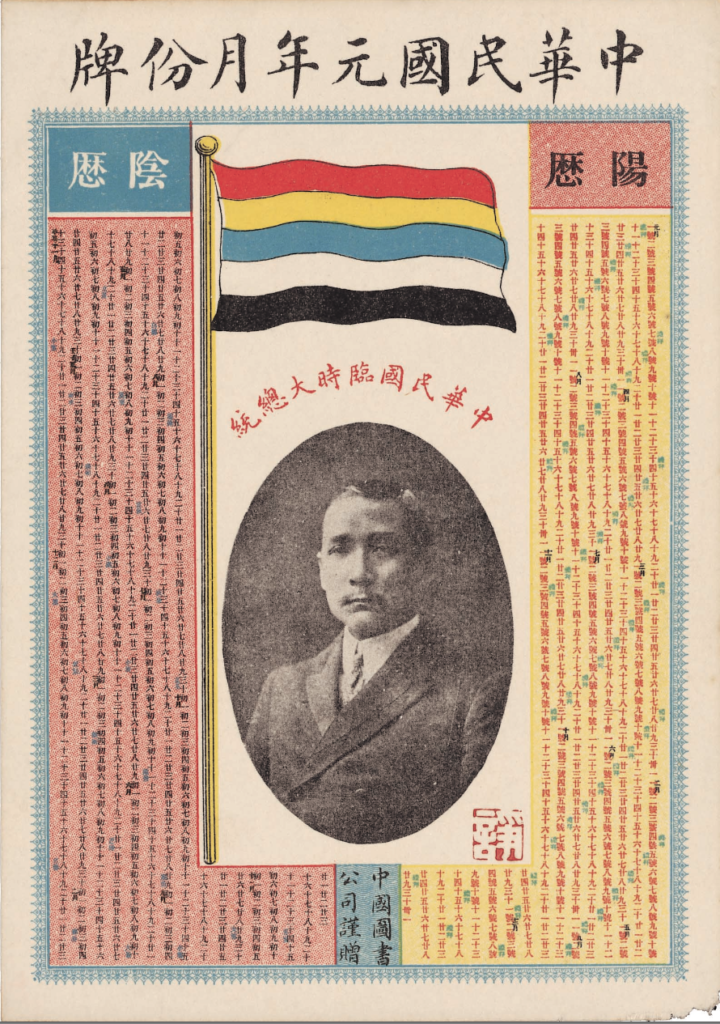

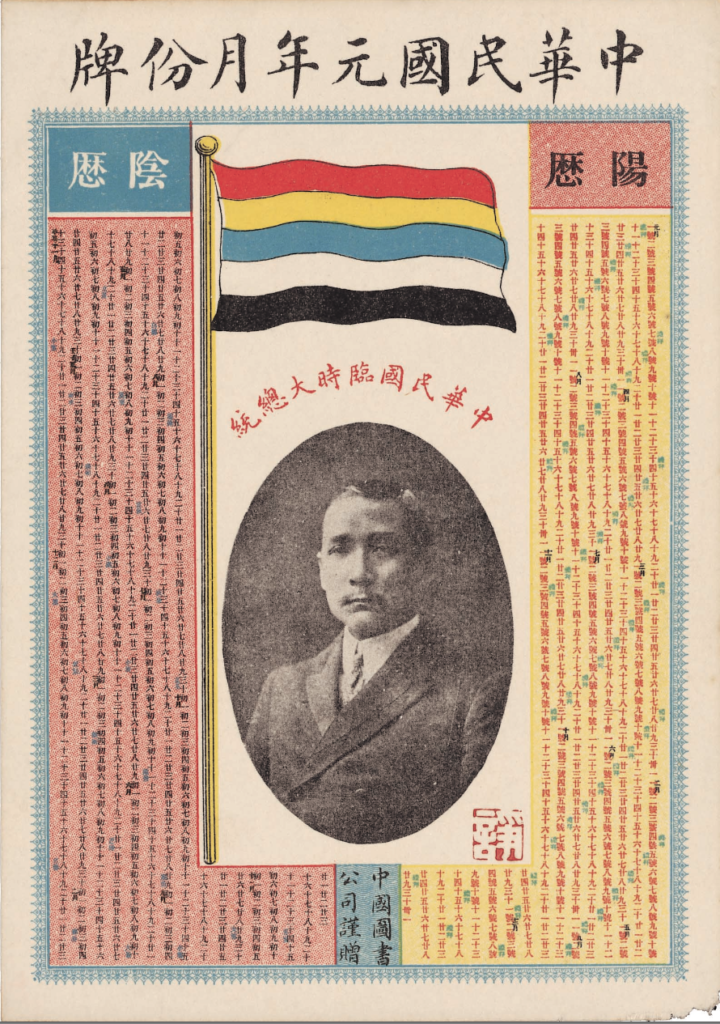

Such a break away from tradition was possible because China was undergoing a profound transformation into a modern nation-state. Reformist intellectuals not only adopted Enlightenment ideology to reshape China’s sociopolitical systems, but also strived to rewrite the country’s cultural history based on “scientific” models provided by Europe and Japan. “Art history” (or meishu shi) entered the Chinese language in 1911 and became a required course in teacher training schools in 1912, the year of the Republican Revolution. Unlike traditional Chinese scholarship on art, which focused exclusively on painting and calligraphy, this modern art history significantly broadened the scope of art to include sculpture and architecture, religious icons and temple murals, tombs and mortuary artifacts, and various kinds of crafts. The concepts of formal beauty and stylistic revolution prevailed in telling this new story of Chinese art.

Calendar poster of the first year of the Republic of China, 1912. Collection unknown. Public domain.

Since that time, generations of scholars have made numerous contributions to substantiate this new discipline. Especially from the 1980s, with the ending of the Cold War and China’s new “Open Door” policy, historians of Chinese art around the world were finally able to converge and share research materials and interests, while scholarly publications, archaeological information, and exhibitions circulated beyond national borders. Such exchanges had an instant impact on Western scholarship on Chinese art, as demonstrated by the many ground-breaking English publications since the 1980s.

On the other side of the Pacific Ocean, the Institute of Art History was established in Taipei in 1990, providing another crucial venue to connect different scholarly traditions on Chinese art. In Mainland China, the field of art history started to expand rapidly after the 1990s. Since then it has produced an astonishing number of books and articles; its appeal to students and young scholars keeps growing. I no longer see a clear distinction between “Western” and “Chinese” scholarship on Chinese art. Differences in language, readership, and academic environment certainly exist, but global collaboration and mutual learning has become the dominant trend.

This progress, on the other hand, has also confronted historians of Chinese art with new challenges. Some of these challenges are more recent, such as how to integrate the linear, regional approach of Chinese art history into a more three-dimensional global art history. Other challenges have always been there, but have remained secondary to the effort to modernize the field. One challenge of this kind is to re-examine key concepts currently used in writing about Chinese art, which are mostly “loanwords” derived from the study of European art. Here I’m talking about concepts as basic as “image,” “iconography,” “style,” “representation,” “gaze,” “monument,” “narrative,“ “evolution,” and many others. While these concepts have facilitated modern scholarship on Chinese art history, their adaptation was not based on first-hand research of China’s art historical reality.

Buddha Maitreya. gilt bronze, dated 486. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I should emphasize that I’m not in any way advocating replacing them with traditional Chinese terms. Rather, I hope that new research on Chinese art will simultaneously reflect on these “universal” concepts vis-à-vis indigenous art practice and discourse, and will in this process redefine these concepts or expand their meaning. Such integrated historical and theoretical projects will in turn encourage comparative studies that will become the basis of a true global art history.

This brings me to the theme of this lecture series, “Chinese Art and Dynastic Time.” At the center of my lectures will be how Chinese art was narrated historically in its original cultural, sociopolitical, and artistic contexts. To tackle this question, I believe we need to investigate the interactions between art practices and historical discourses on art. Art practices encompass everything related to the creation, presentation, and circulation of works of art. Historical discourses on art embrace all the sorts of writings produced in the same culture milieu that describe and interpret art practices, including history, mythology, philosophy, ritual prescription, hagiography, as well as art historical scholarship.

The most powerful and lasting narrative framework of Chinese art has been dynastic time, which organizes historical information and channels the historical imagination through successive dynasties from the third millennium BCE to the twenty-first century CE. As I will explain later in this lecture, this narrative first emerged around the fourth century BCE. Twelve hundred years later, when Zhang Yanyuan (ca. 815–ca. 877) wrote the first comprehensive narrative of Chinese art in the ninth century, he explicitly titled it Famous Paintings of Successive Dynasties (Lidai minghua ji).

Portrait of Daoxuan (596–667), 14th century. Nara National Museum.

The same mode of dynastic time still dominates our understanding of Chinese art today. A glance at the tables of contents in current introductions to Chinese art immediately reveals this fact. Michael Sullivan’s Art of China, now in its sixth edition, has 12 chapters and progresses through various dynasties—the Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han, Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing—til the 20th century. By folding the 20th century into this structure, this and similar textbooks implicitly incorporate Modern and contemporary art into a linear narrative based on dynastic time. So deep-rooted is this temporal order in Chinese art history that it seems to have become self-evident and natural, as an a priori and shared chronology that escapes historical scrutiny. As a result, although the field of Chinese art produces huge quantities of research every year, there has been little reflection on the nature of this temporal framework and its role in both the discourse and practice of Chinese art.

My inquiry into the narrative of Chinese art thus acquires a sharp focus, i. e. the nature of dynastic time and its role in shaping the history of Chinese art. As proposed earlier, the symbiotic relationships between practice and discourse will be the focus of my discussion. Many questions will arise along this line of inquiry. For example, how did dynastic time emerge in the discourse on art and infiltrate contemporaneous art practice? How did this narrative mode constantly redefine itself in changing historical contexts? How did it interact with other temporalities of divergent historical, religious, and political systems? How did historical narratives based on dynastic time both respond to and inspire artistic creation? As these questions indicate, these lectures perceive the history of Chinese art not as a retrospective reconstruction of later art historians, but as an evolving process which fosters its concepts and vocabulary alongside the invention of art works, mediums, and styles, not after such inventions.

Wu Hung’s remaining A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts will be presented on April 28, May 5, and May 12 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Audio of his previous three talks can be found here.