Up Next

Xiyao Wang’s Balletic Paintings Are Inspired by the Changing Seasons

The artist's sparse and elegant works are making waves on the international stage.

“My understanding of painting keeps changing, so the images I go after and the artistic expressions I aim for are always shifting,” artist Xiyao Wang (b. 1992) said from the other side of the computer screen. At that moment, she was sitting by a serene lake in the Swiss countryside, having just returned from a busy trip at Art Basel where she showed with Massimo De Carlo. After a brief rest, she was about to depart for Milan, where she would have her first solo exhibition in Italy at the gallery’s flagship space.

Xiyao Wang, installation view of “The Blue Hour”. Photo by Roberto Marossi. Courtesy Massimo De Carlo

The Berlin-based Chinese artist describes her process as “cyclical,” in which she focuses on the study and exploration of lines. In her solo exhibition at Perrotin New York in January this year, she began to show the “subtraction” works she had made: the canvases featured more black-toned charcoal lines, with light oil sticks mixed with coarse charcoal. These paintings were created during the winter. “Berlin’s long winter has no color, and it seemed as if the whole world I could see was just in the shades of black, white, and gray.”

Xiyao Wang at her exhibition “The Blue Hour” at Massimo De Carlo’s Milan gallery

Wang’s understanding of painting is ever-evolving, stemming from her continuous absorption and discovery of the surrounding world. “I discovered that painting is my favorite medium, possibly something I want to do for a lifetime. Painting is the most direct; I can touch it directly with my hands and complete the entire process alone. I really like this tangible and direct way of expression.”

She spread her arms on the screen, describing herself as a sponge. “This is a kind of talent. I feel my senses are completely open as if every pore on my body is constantly absorbing.”

Xiyao Wang, installation view of “The Blue Hour”. Photo by Roberto Marossi. Courtesy Massimo De Carlo

After solo shows at Perrotin New York and the Song Art Museum in Beijing, she returned to her Berlin studio in January, opting for seclusion, away from the outside hustle and bustle of the city. She awaited the end of the prolonged Berlin winter.

Spring finally arrived. “I would take walks on weekends in the forest and observe the tiny buds emerging, then gradually changing colors,” Wang said. She deliberately observed the blooming and fading of plants at different times in the forest. She began to paint around sunset, after hours of Taoist rituals to calm herself and get in the zone, including reading, tea ceremonies, and guqin practice (a seven-stringed Chinese instrument with a history of thousands of years). At the pre-sunset moment, she discovered the burst of blue hues in the sky after sunset and before complete darkness.

“The whole sky goes from light blue to deep blue, to the most intense blue, so breathtaking that it takes your breath away.” Wang feels colors extremely vividly and intensely. “I suddenly had a strong desire to express myself. Unable to convey them all in words, I found a paint closest to that sky color and expressed the point that touched me the most. This new batch of works carries my gratitude and emotion toward nature.”

She began using different materials to draw lines, seeking to break through limitations within the constraints of the materials to find the freest state of lines. “I’ve never stopped exploring how to use different speeds, rhythms, weights, thicknesses, and turns to outline, break, and ultimately traverse space on the canvas, accurately yet without tension, exuberantly yet not frivolously.”

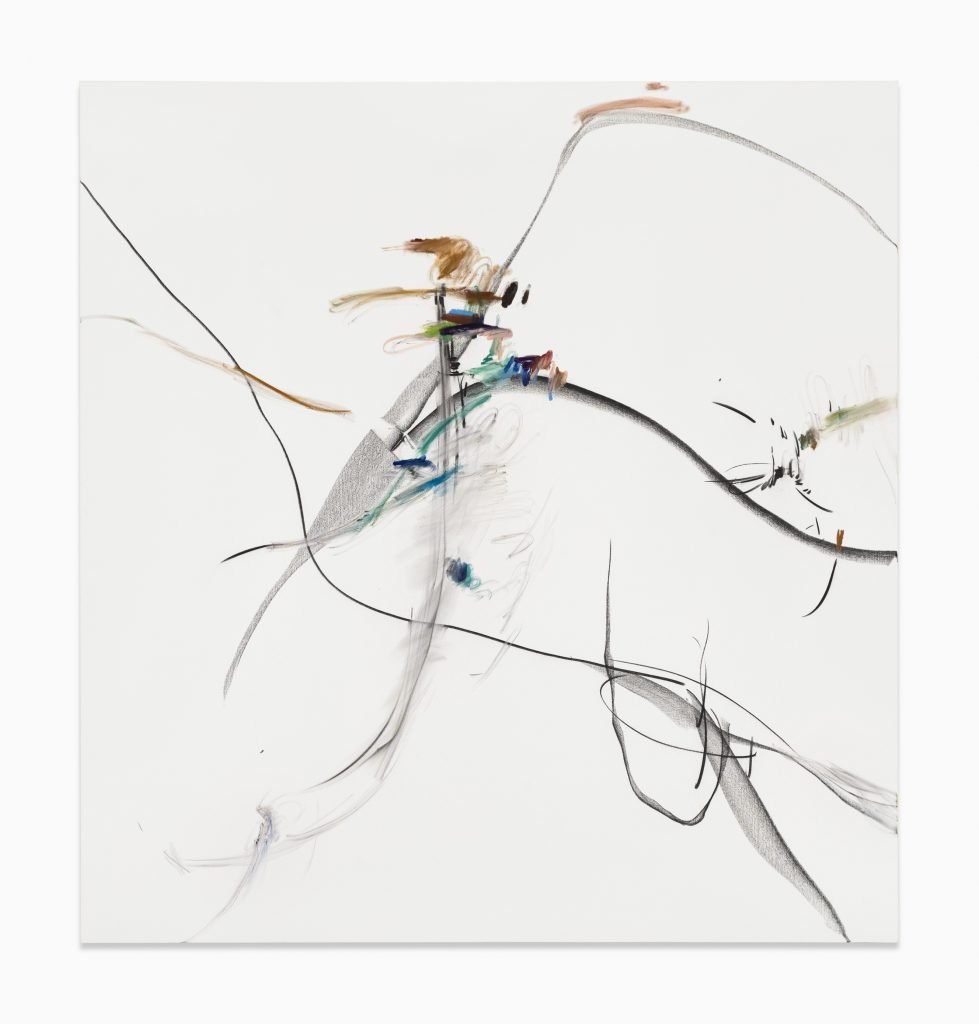

Xiyao Wang, The Blue Hour No. 1, 2024. 200x190cm. Courtesy of the artist and Massimo Di Carlo

In The Blue Hour No. 1, the azure blue is just a small cluster on a sprawling canvas (200 by 190 centimeters). Oil stick, a tool Wang is very familiar and proficient with, are used to let a small touch of color tightly intertwine. Meanwhile, the charcoal, like limbs extended in a graceful dance, stretches out freely. As if marks are created by a suspending astonishing colored hummingbird. The contrast of jumping and extending, of unrestrained and cautious, forms a striking juxtaposition.

This boundless, carefree, and light state originates from Wang’s muscle memory from her early dance training and recent ballet practice, where she realized the connection and alternation between body movements and painting. “They can complement and even inspire each other, but they cannot replace one another. They, along with many other elements, are part of my life and thus have become part of what influences my painting.”

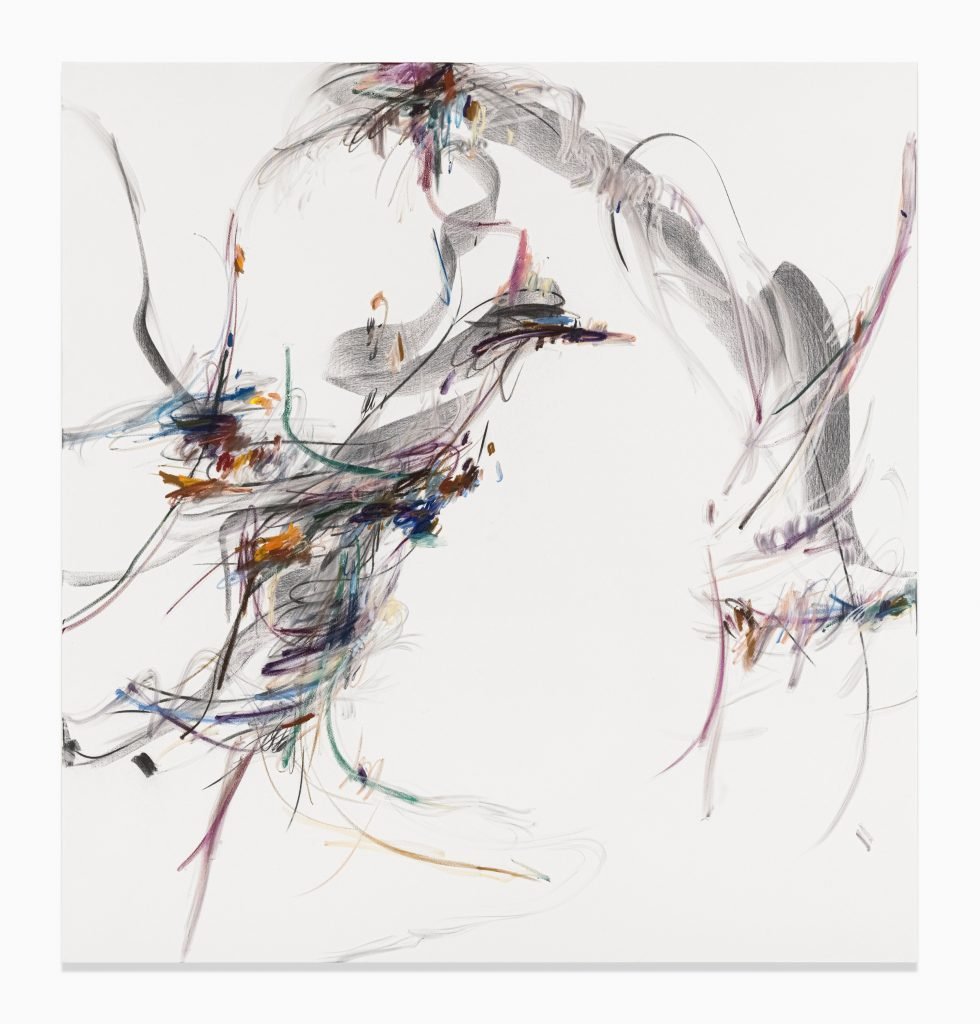

Xiyao Wang, Échappé No. 1, 2024. 200x190cm. Courtesy of the artist and Massimo Di Carlo

Adagio and Échappé, two ballet terms (Adagio refers to slow, graceful movements, while Échappé involves quick footwork), were also named in her new paintings. “For me, Adagio is not just a ballet term; I inherently love the free and gentle flying posture.” She also compares it to the flying figures in the Chinese Dunhuang murals, a weightless beauty that is fluid and balanced, which is part of her life and the state she ideally wishes to achieve.

Wang also gave the exhibition a Chinese name “阳春召我以烟景”, derived from a poem by the Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai in which he celebrates the fleeting moment. She was also quite pleased that the interview was conducted in Chinese so that she could discuss the most accurate English translation with me. Among all the versions she sent, I chose “Primavera calls me with its airy scene.”

In recent years, this artist has increasingly traced back to her cultural roots. She feels that whether it’s the spring in Li Bai’s poetry or the playing of the guqin, it is a response to nature, and also her cultural roots. Wang said that in Taoist tradition, the guqin is also used to aid meditation, with many playing in the mountainous woods or in front of waterfalls, and often the playing imitates natural sounds like flowing water, wind blowing, and birds chirping.

Xiyao Wang working at her studio in Berlin

For many artists of her generation, Wang’s resume is enviable. In addition to Massimo De Carlo, she is co-represented by Perrotin, Tang Contemporary Art, and König Gallery. Since 2022, her solo exhibitions have been held globally, including solo projects at major art fairs, most recently at Art Basel with Massimo De Carlo.

She belongs to a generation that welcomes and skillfully uses social media. You can always expect impressive updates on her Instagram, including visits from art world heavyweights to her studio. Her iconic single earring with the Chinese characters “不接受批评” (not accepting criticism) makes her quite controversial in the humility-valuing Chinese environment.

Xiyao Wang working at her studio in Berlin

“I am, in fact, someone who is very accepting of criticism,” Wang recalled, reflecting on her student years when she would show her paintings to artists and teachers, seeking their opinions and critiques. “But now, other people’s opinions are not as important to me. If there are too many different voices around, you find yourself unable to start. I prefer to ask myself what I really want, then learn and do a lot of research based on that. I set different goals for myself at different stages.”

“What is it that you ultimately want?” I asked.

“I want to be the greatest artist, like Louise Bourgeois, whose works can always move people, transcending time. This is something I will do for a lifetime, even though I may not reach it in a lifetime. But having a goal to move towards always makes me happy.”