Step aside, Google; Yale University has entered the chat.

Earlier this month, the university unveiled Lux, its new online platform that allows users to search across the 17 million objects in its massive holdings, which span the collections of the Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Center for British Art, Yale Peabody Museum, and Yale University Library. The project was made possible by a grant from the Mellon Foundation, in addition to funding from the university.

As a research tool, Lux enables interdisciplinary exploration as well as discovery. Besides surfacing objects alongside their detailed descriptions, the platform aims to build and highlight all the relationships possible between artifacts. For example, a search for John Trumbull’s The Declaration of Independence (1817–18) will also call up related objects from a pistol the painter once owned to a trove of his sketches and plans, which are held in YUAG’s library.

John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776 (1817–18). Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

“The power of Lux comes from its ability to allow users to uncover hidden relationships between objects, from shared concepts to famous figures in Yale’s collections,” said Robert Sanderson, Yale’s senior director for digital cultural heritage, in a statement.

While not all the objects in Yale’s collections have been digitized, said Susan Gibbons, vice provost for collections and scholarly communication, at a press preview, most have been. “There are no dead-ends in Lux,” she emphasized.

Lux mirrors similar platforms such as Van Gogh Worldwide and the Duchamp Research Portal that allow for cross-collection and relational explorations in ways that trump a simple Google search. As Sanderson noted at the same press event: “No one likes to search; everyone likes to find.”

In that same spirit, we took a spin on Lux to see what previously unseen treasures might be unearthed from Yale’s vast collections. Here’s what we found.

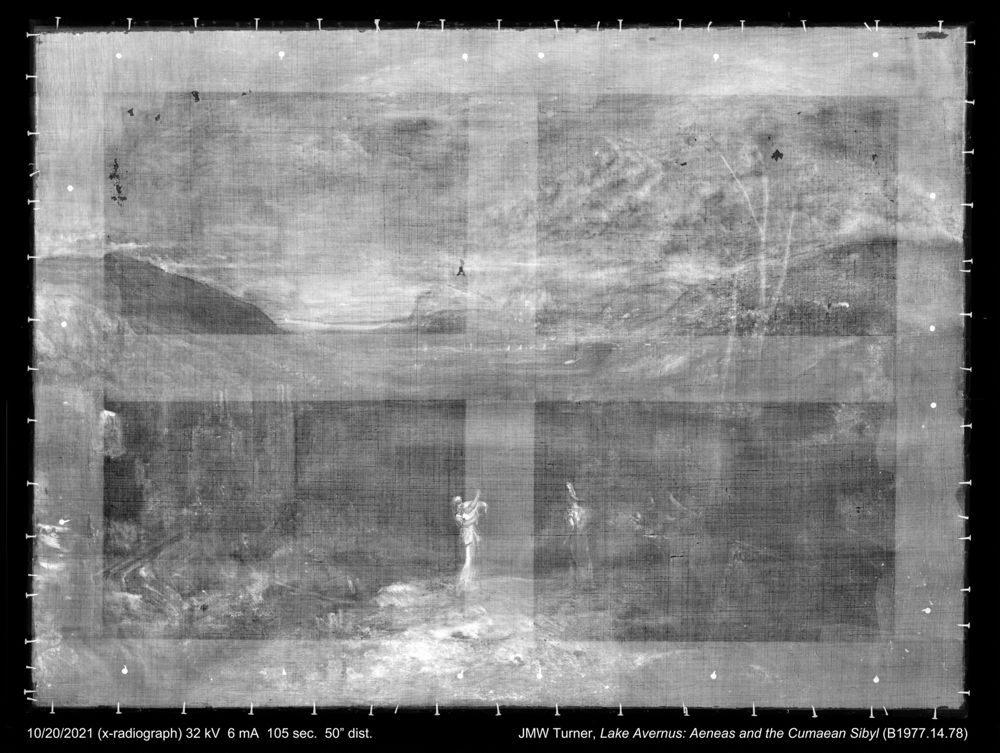

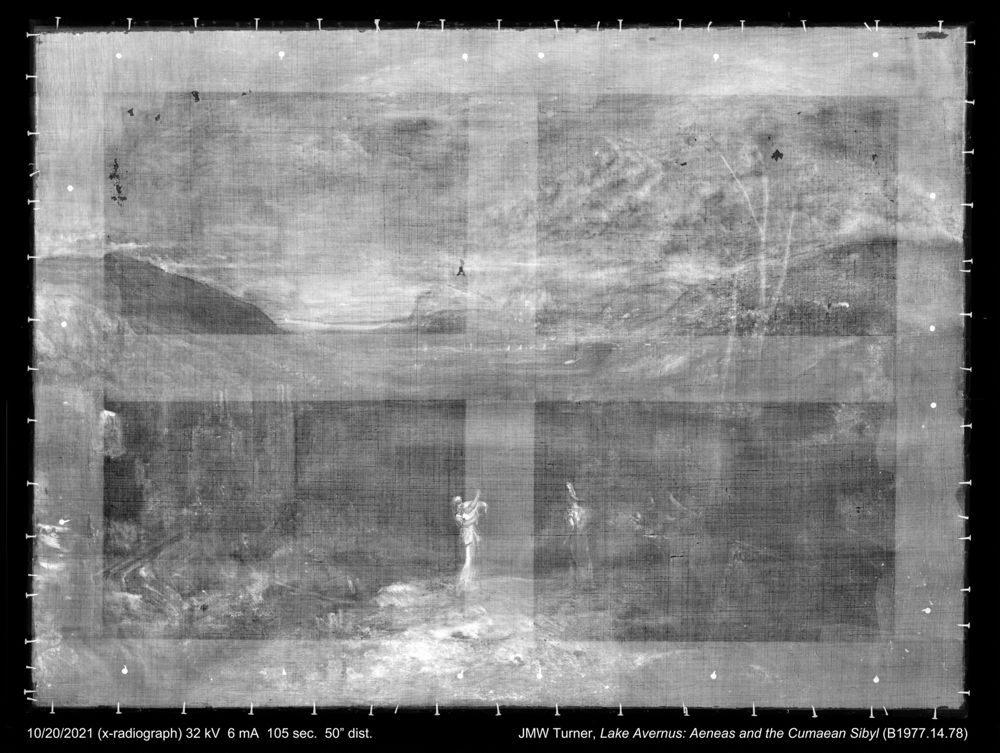

An X-radiograph of J.M.W. Turner, Lake Avernus: Aeneas and the Cumaean Sybil (1814–15). Photo courtesy of Yale Center for British Art.

One of the joys of Lux is discovering paintings that have been photographed from every possible angle, including using X-rays. Turner’s mythical landscape, held in the Yale Center for British Art, is just one work catalogued with high-definition images capturing its recto and verso (which, by the way, still bears a Christie’s sale tag from 1883), as well as a radiograph that offers an in-depth view right down to the last nail in the frame.

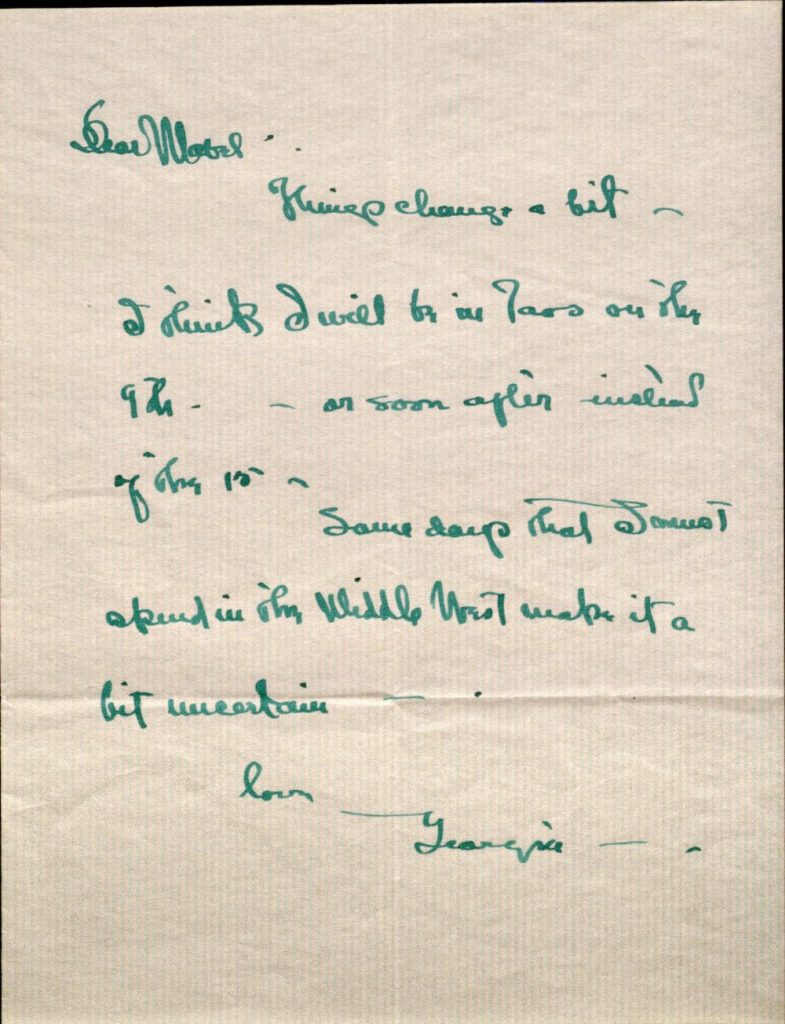

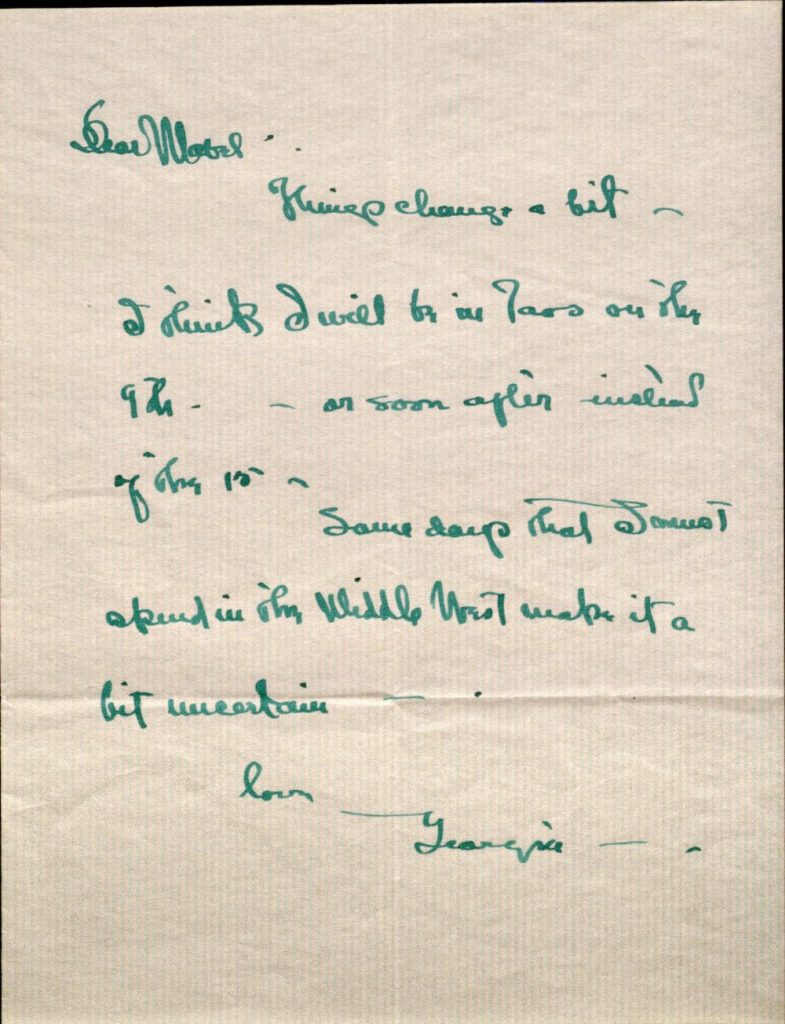

A letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Mabel Dodge Luhan (1925–52). Photo courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University Library.

It was the arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan who, in the late 1910s, first lured painter Georgia O’Keeffe to New Mexico—launching the artist’s love affair with the southwestern landscape and a decades-spanning correspondence between the pair. Collected at the Yale Library, this hoard of letters, by turns prosaic and tender, documents O’Keeffe’s creative process, relationships, and everyday life, as well as the eventual dissolution of her relationship with Luhan (allegedly because O’Keeffe had an affair with Mabel’s husband, Tony Luhan).

Triceratops prorsus in situ, Vertebrate Paleontology Collection, Yale Peabody Museum. Photo: courtesy Yale Peabody Museum.

When paleontologist John Bell Hatcher unearthed the first complete skull of a female Triceratops in Wyoming, it heralded the discovery of a whole new species of dinosaur. His find was undertaken as part of the 1889 Yale Hatcher Cretaceous Expedition, and was sent on to Othniel Marsh, then the dean of dinosaur exploration at Yale, for further study. Lux logs other discoveries on the expedition, which includes a wealth of teeth, mandibles, and vertebrae, all held by the Yale Peabody Museum.

Cornelis Engebrechtsz, The Deposition (c. 1510–20). Photo: courtesy Yale University Art Gallery. Bequest of Dr. Herbert and Monika Schaefer.

In another boon for art historians, Lux’s artwork entries, where possible, detail the provenance of each object. Cornelis Engebrechtsz’s The Deposition (c. 1510–20), for instance, is just one of the vast number of Nazi-looted paintings, its protracted provenance section on Lux describing its original Parisian owner, one Baron E. Etienne-Edmond-Martin de Beurnonville, its sale to a Berlin dealer, likely on behalf of Hermann Göring, before its eventual donation to YUAG.

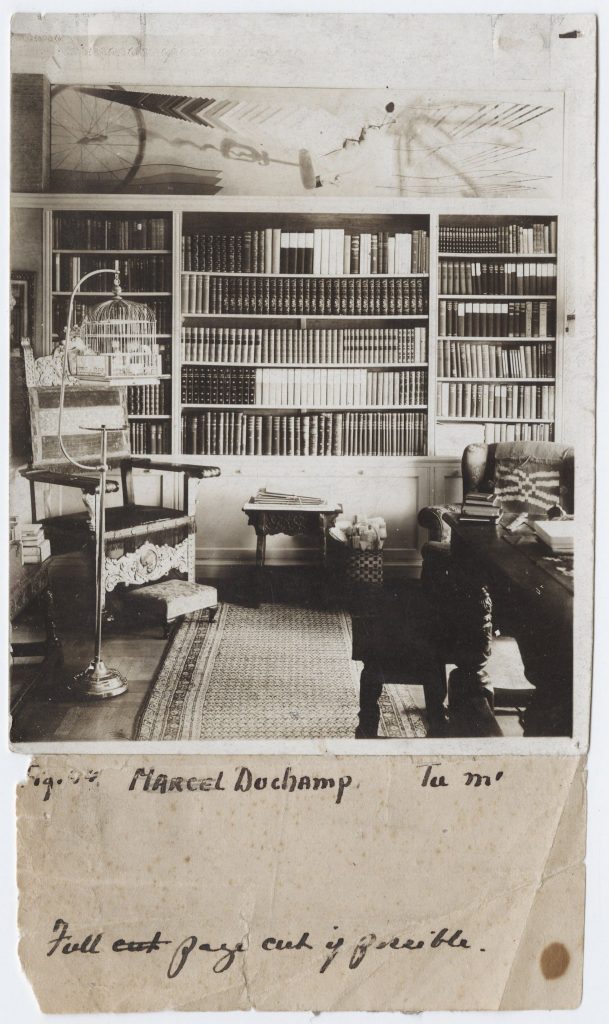

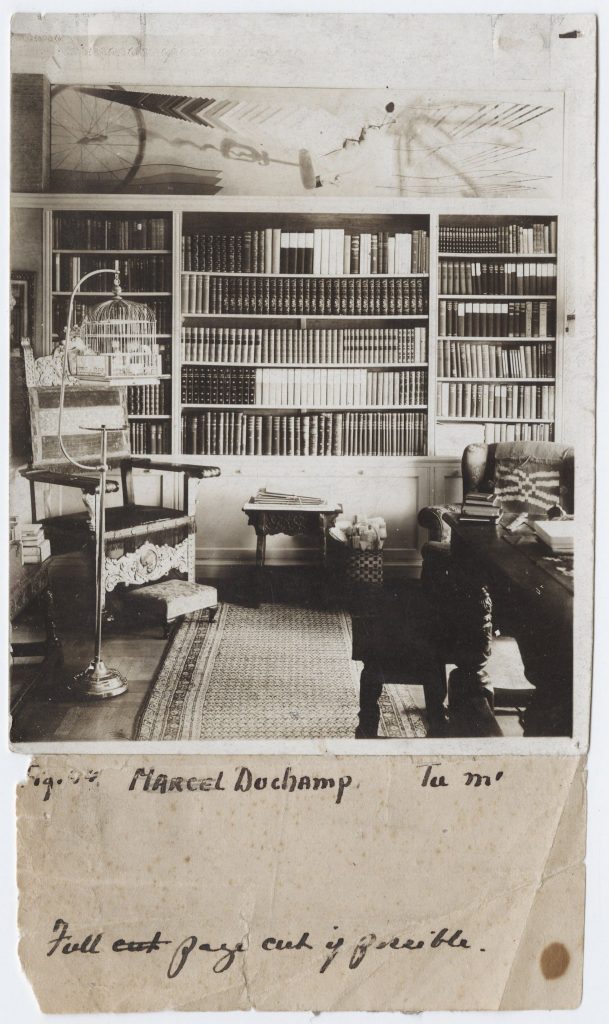

Katherine S. Dreier’s apartment at 135 Central Park West in New York with a view of Marcel Duchamp’s Tu m’ over bookcases (c. 1918), from the Collection: Dreier, Katherine S., 1877-1952. Photo courtesy Yale University Library.

Besides being an accomplished (if under-recognized) painter, Katherine Dreier was a fervent champion of Modern art, founding the Société Anonyme in 1920 with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp to promote the emerging avant-garde. Her archive, which she donated to the Yale University Library, documents the organization’s activities from 1920–51 in objects from files on artists to brochures to photographs.

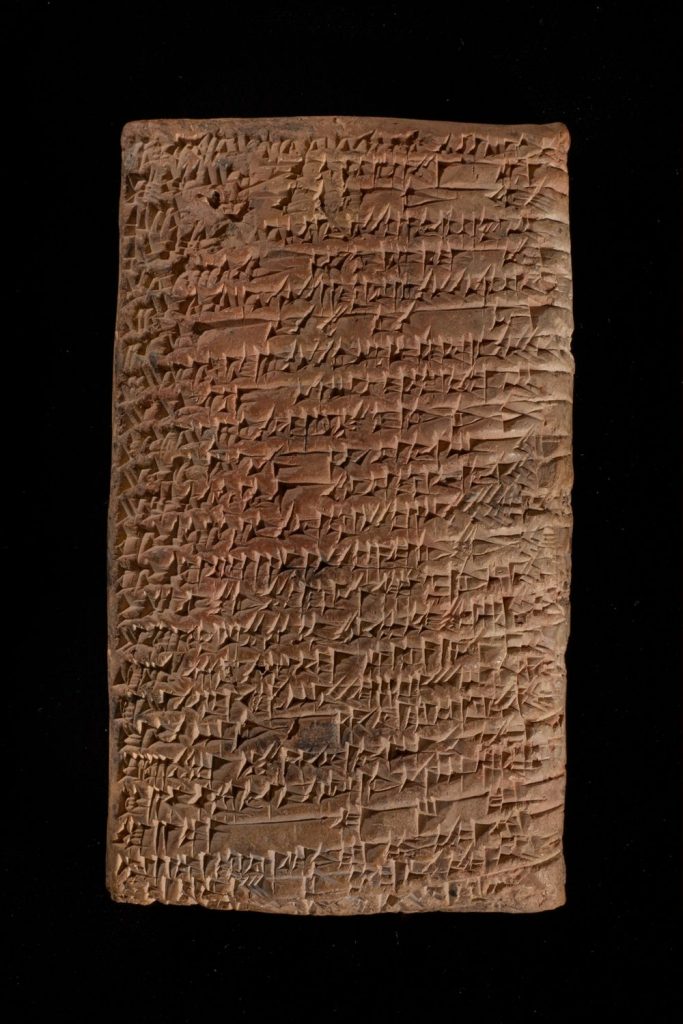

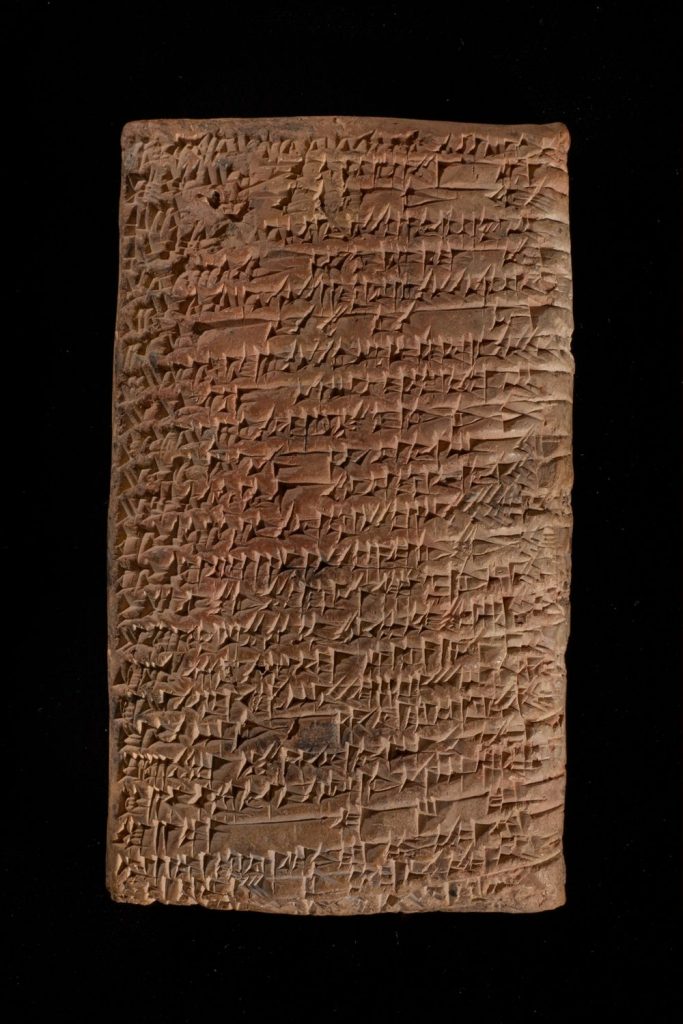

Hymn to Inanna on clay tablet, lines 52-102 by Enheduanna. Photo courtesy Yale Peabody Museum.

Enheduanna was a Mesopotamian priestess whose poetry, inscribed on clay and alabaster tablets first excavated in the 1920s, have made her history’s earliest known author. The Yale Peabody Museum’s enviable Babylonian collection has her Hymn to Innana, a passionate ode Enheduanna penned 4,200 years ago to the Mesopotamian goddess. Alas, the entry does not contain a translation of the poem, which proclaims: “You alone are majestic, you have renown, heaven and earth.”

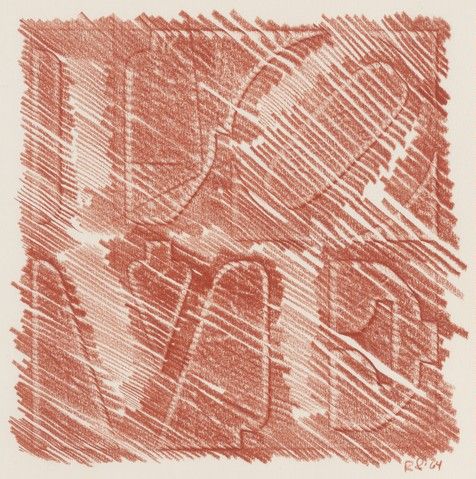

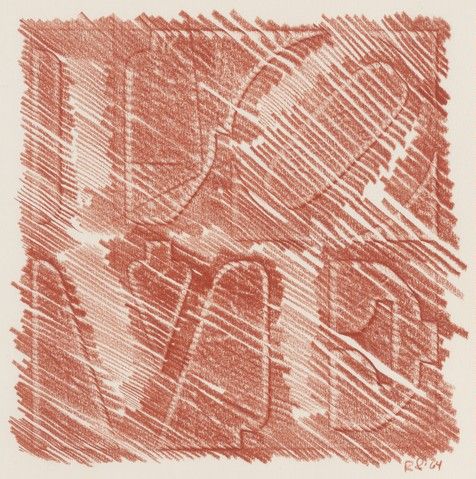

Robert Indiana, Love (1964), from the Richard Brown Baker, B.A. 1935, Collection.. Photo courtesy Yale University Art Gallery.

In his lifetime, Baker amassed one of the largest collections of Modern and contemporary art, his hoard numbering some 1,600 works by the likes of Jackson Pollock, Roy Lichtenstein, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Jean Dubuffet. “It would be helpful and challenging,” he decided in the 1950s, “to buy the work of the living, the young, and the unestablished.” Upon his death in 2002, Baker gifted three-quarters of his collection to Yale, his alma mater. Not all of his bequest is on view, but it can be found gathered on Lux, attesting to the scope of his collecting efforts.